The Purchasing of the Almirante Cochrane and Blanco Encalada Ironclads

By Eddie Cerda Grollmus

Part 1 ||

Part 2 ||

Part 3 ||

Part 4The idea of providing Chile with armored ships dates back to 1864. It has its genesis in the events that led to the war between the allied side (Peru and Chile) against Spain, as a result of the occupation by the squadron of the latter. of the Chinchas Islands, at that time the main source of foreign exchange in the Peruvian economy (exploitation of the Guano). The first promoters of this idea were Messrs. Manuel José Irarrázaval (Former Minister of the Interior), Federico Errázuriz (Minister of Justice, Worship and Public Instruction), and Alejandro Reyes (Minister of Finance), they advocated the acquisition of two monitors or armored vehicles that were powerful enough to counter the Spanish squadron at that time in the Pacific 1.

Then the Interior and Foreign Relations portfolio was occupied by Abdón Cifuentes, who continued with the idea of such an acquisition, but given the poverty of the national treasury and the opposition of the then president José Joaquín Pérez Mascayo, Abdón Cifuentes' attempts were in vain. These were maintained throughout the decade in which Pérez governed (1861-1871).

The main consequence of this refusal was the bombing of the port of Valparaíso (March 31, 1866), by the Spanish fleet. The president's lack of vision resulted in the almost disappearance of the national merchant marine 2, and only the destruction . of the port cost close to 15,000,000 pesos 3.

After the war with Spain (1864-1866) ended, Chile could not take out the O'Higgins and Chacabuco corvettes from the English shipyards given the blockade imposed by England claiming neutrality in the conflict. In the same way, England had blocked the delivery of the Armored Frigates. “Victoria” and “Arapiles” to Spain, before this Spain reached an agreement with Chile (1868), which stipulated that for Chile to be able to take out its corvettes it had to commit to acquiring war supplies in England or any other state until the sum was equal. invested by Spain in its two frigates, the difference amounted to 403,000 pounds (540,000 pounds had cost the Spanish frigates and 137,000 the Chilean corvettes). Given the status of allies between Chile and Peru, the Chilean ministers in Europe, Maximiano Errázuriz and Alberto Blest Gana, informed their counterpart from Peru, Jara Almonte, who gave his approval, so on February 18, 1868, the agreement reached was submitted to the public. of the English government, but on March 5, 1868, Alberto Blest Gana was surprised by a note from his Peruvian colleague Jara Almonte in which he vetoed the agreement and indicated (verbally to Lord Stanley) that a state of war existed between Chile and Peru. , it happened at that time that President Mariano Ignacio Prado (1865-1868), had been replaced by Pedro Díez Canseco (1868), and the latter by José Balta (1868-1872), who took a turn in their foreign policy regarding to his former ally 4.

In 1871 5, Federico Errázuriz Zañartú won the presidency of Chile, and sent to Congress the bill that authorized the executive to acquire two armored vehicles, the project was approved with only one vote of rejection (that of the previous president José Joaquín Pérez Mascayo) , it was agreed that these armored vehicles would be of medium size (Second Class Armored), both ships were commissioned in 1872, at a cost of 2,000,000 pesos, this amount was approved by the congress authorized the president of the republic to hire a loan abroad for the total and allocate it only for the acquisition of said ships, in reality the total amount approved corresponds to $2,200,000 of which the 200,000 would be used for the construction of the Magallanes Gunboat, I will not go into more detail about this vessel since it is not relevant to topic 6.

Minister Alberto Blest Gana was commissioned to carry out all the arrangements in this regard. Blest Gana contracted the designer of the ships (E.J. Reed, former Naval Architect of the Admiralty), as Technical Advisor, who recommended lining the interior with Teak and Zinc wood in order to To improve its stability and protection, it also contracted the Earle's Shipbuilding Co shipyard, in Hull, Yorkshire, England for its construction, as well as other equipment for the ships (weapons, machines, etc.).

The Armored would be called Cochrane and Valparaíso, the first of them was commissioned in April and the second in June 1872, then to make the supervision of their construction closer, Captain Leoncio Señoret Montagne was sent to England, even so the construction Both suffered delays for different reasons, including worker strikes, unfit personnel, rain, and price increases in coal and iron 6.

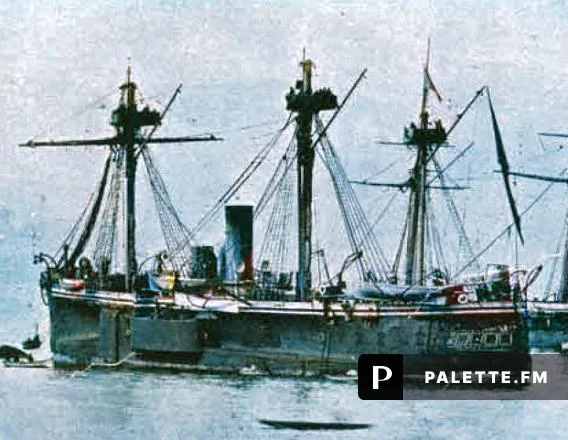

Almirante Cochrane Armored Frigate

Almirante Cochrane Armored Frigate The previously mentioned situation (the delay) was aggravated given the new tensions between Chile and its neighbors Bolivia and Argentina due to treaty and boundary issues, the demonstration of force carried out by Peru in mussels as a result of Quevedo's expedition to the Bolivian coast. (1872), in which the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Peru, José de La Riva Agüero, had expressed the surprise with which Peru viewed the purchase of two Armored Vehicles and that Chile did not need them for its defense 7.

In 1873, the Treaty of Defensive Alliance was signed between Peru and Bolivia (obviously this was secret and Chile was not aware of it), and Peru's attempt to extend this alliance to Argentina, given the above, the president ordered that work be done day and night. night in the armored Cochrane (at the time the most advanced), and to set out for Chile as soon as possible, the Cochrane arrived in Valparaíso on December 25, 1874, without the wooden and zinc lining and other details that would not prevent its use. as a war unit.

It was known, and this is demonstrated by the correspondence between President Errázuriz and his minister in Europe Alberto Blest Gana, that if a conflict broke out in the region, Chile would not be able to remove its ships from the shipyards, given the blockade that England would impose8

At that time, Chile was in talks with Bolivia that would result in the treaty of 1874, which was finally ratified by the Bolivian Congress. Argentina ultimately did not adhere to the treaty with Peru and Bolivia. The history of Chile indicates that there are two reasons for this: presence of Cochrane (the one that is most often referred to), and the territorial dispute with Bolivia over Tarija and a sector of the Chaco, I do not know which of the two weighed more in the decision, but I tend to think that it was more the second, given the details exposed in the negotiations of said treaty 9.

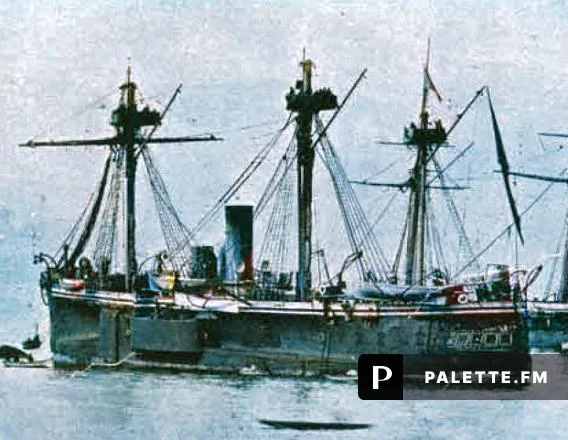

On January 24, 1876, the “Valparaíso” arrived in Chile, which unlike her sister ship (Cochrane) was completed and with all her rigs. On September 5, 1876, Admiral Blanco Encalada died (one of the heroes of the independence of Chile, who in 1818, in command of the squadron, captured a convoy and the Spanish frigate María Isabel that escorted it, and was also the commander in chief of the first expedition against Santa Cruz in the War Against the Peru-Bolivian Confederation with meager results), at the age of 86 and in recognition of his military merits, the name “Valparaíso” was changed to “Blanco Encalada”.

Blanco Encalada (former Valparaíso) Armored Frigate

Blanco Encalada (former Valparaíso) Armored Frigate In January 1877 the armored Cochrane was sent to England for completion and fairing, arriving in Chile again in 1878.

The armored vehicles had brigantine rigs, they displaced 3,560 tons, the power of their two engines (which moved two propellers) gave them 2,960 HP of power, their dimensions were: 210 feet in length (64 meters), 45 feet and 9 inches in height. beam (14 meters), draft 19 feet and 8 inches (6 meters), bunker capacity of 254 tons, speed 12 knots, and 300 men crew 10

The armament consisted of 6 9-inch (230 mm approx.) Armstrong muzzle-loaders, housed in a central casemate distributed three per side, capable of launching a 250-pound (113.5 kilo) grenade, each piece weighing 12 tons, and They were mounted on a Scout gun carriage with a central pivot. These pieces are installed in a central casemate and allow the bow gun to fire from the front to the beam, the central piece fired with an angle of 70º to the bow and 35º to the stern and the third from from the beam to the stern, her armament was completed by a 20-pounder cannon, one 9-pounder and one 7-pounder. The Blanco Encalada was equipped, in addition to the cannons, with 2 Noldenfeldt machine guns, the Cochrane only had one installed on the “apostle.” from the bow, its caliber was one inch (2.54 cm), and it fired a bullet weighing one pound (454 grams), 10.

Armstrong 9-inch gun, Blanco Encalada Ironclad.

Armstrong 9-inch gun, Blanco Encalada Ironclad. The ships had a double hull and 7 watertight compartments, the armor was composed of a 9-inch (approximately 230 mm) shell in the central strip that was reduced to 4.5 (114.3 mm) in the bow and stern, The teak covering was 10 inches thick 10.

The Ram was shaped like a ram with a length of 7 feet (2.1 meters), submerged at 6 feet and 9 inches (2.06 meters), below waterline 10.

In January 1878, and faced with the economic problems, President Aníbal Pinto commissioned the Minister in Europe, Alberto Blest Gana, to put the ships up for sale as soon as the dispute with Argentina was resolved, commissioned by the Minister, the designer of the ships (E.J. Reed), offered Cochrane to England for 220,000 pounds sterling, the country was not interested, then an attempt was made to sell the two armored vehicles to Russia, obtaining the same result, in this way an attempt was made to alleviate the economic crisis that had prevailed in the country for some time. years 11..

Fortunately for Chile, the sale of the armored vehicles was frustrated, a situation that would have been critical in the event of a war, in some way these ships acted as a deterrent element, even so for the start of the Pacific War they required deep maintenance, their bottoms were dirty (accumulation of mollusks and other marine living beings), the boilers needed to change tubes and their machinery had to be completely serviced, the speed of the ships was limited to 9 knots, there was no dock in Chile for these ships and given the economic crisis It was impossible to send them to Europe to be faired. Of the two armored vehicles, the Cochrane was in better condition, in terms of its bottom cleaning, but not the machinery and boilers. This situation was the same in all units of the squadron except the Magallanes Gunboat.

Both armored vehicles were the fundamental axis of the squadron in the Pacific War (1879-1884) and strictly speaking the only ones truly of war and for 13 years they were the backbone of the Chilean Navy.

Notes

1. Historia de la relaciones Internacionales de Chile, Don Adolfo Ibáñez Su gestión con Perú y Bolivia, Ximena Rojas Valdés, Editorial Andrés Bello, 1971, Santiago, página 72.

2. La Armada de Chile: Desde la Alborada al Sesquicentenario (1813-1968), Rodrigo Fuenzalida Bade. Santiago, Chile: 1978, Empresa Periodística Aquí Está, Tomo III página 681. In 1861 there were 267 Chilean vessels totaling 60,847 tons, in 1864 there were 232 vessels, in 1867 there were 19 sailboats (2,7580 tons) and 2 steamers with 644 tons, in 1871 there were 75 vessels (14 steamers), totaling 15,870 tons.

3. $14,773,700, which was distributed as follows: private buildings $633,000; fiscal buildings $550,700; furniture and merchandise in private buildings $1,500,000; merchandise set on fire at customs $12,000,000; miscellaneous damages $30,000; Of the destroyed merchandise, $8,300.00 belonged to Foreigners and $3,700,000 belonged to Chileans. La Guerra Entre España y las Republicas del Pacífico, Alfonso Cerda Catalán, Editorial Puerto de Palos, Chile páginas 252-253.

4. See Historia de la relaciones Internacionales de Chile, Don Adolfo Ibáñez Su gestión con Perú y Bolivia, Ximena Rojas Valdés, Editorial Andrés Bello, 1971, Santiago, página 73 y La Armada de Chile: Desde la Alborada al Sesquicentenario (1813-1968), Rodrigo Fuenzalida Bade. Santiago, Chile: 1978, Empresa Periodística Aquí Está, Tomo III páginas 682-683.

5. By then, Peru had in its naval inventory the armored frigate “Independencia” (1866), monitor “Huascar” (1866) and the river monitors “Manco Capac” and “Atahualpa” (both arrived in 1870).

Independencia was commissioned in 1864, in anticipation of the events of the Chichas Islands, built in England by J.A. Samuda for 176,600 Pounds Sterling, displaced 2,004 tons, armored 4.5 inches, had a ram and was armed by 1 Vavasseur of 250 pounds in the bow, 1 Armstrong of 150 pounds in the stern and 12 Armstrongs of 70 pounds, or 6.4 inches, displaced in the central battery, all scratched.

Sources:

Peru Sovereign Guerra del Pacífico The Huáscar had its origin in the same events of the Chinchas Islands, it was commissioned to the Laird Brothers shipyard, Birkenhead, Poplar on Thames, England, designed by Captain Cowper Coles of the Royal Navy, under the "Ericsson" model.

The case had a double bottom and was divided into five watertight compartments, it displaced 1,130 tons, it had two engines that gave it a power of 1,500 horsepower and that moved a single propeller, it was protected by 4.5 (11.43 cm), inches of armor in the center that decreased to 2.5 fore and aft (6.35 cm), its main armament was a pair of 10-inch (254mm) muzzle-loading rifled Armstrongs, capable of launching a 300 lb grenade ( 136.2 kilos), mounted on a circular rotating tower installed in the bay, (Coles Tower), 30 feet in diameter (9.1 meters), manually moved, whose armor was 5.5 inches (14 cm), completed Its armament is 2 Armstrong of 40 pounds (18.6 kilos) on the port and starboard sides and 1 of 12 pounds (5.5 kilos) on the stern, coal capacity 300 tons, speed 11 knots.

Sources:

Armada Chile Peru Sovereign The river monitors Manco Capac and Atahualpa belonged to the Canonicus class built at the Niles & Rivers Works shipyard in Cincinnati, Ohio, by the Union Navy of the United States of North America, at the time of the Civil War, the first It was named Oneota and the second Catawaba, both were acquired by Peru in 1868.

Both displaced 2,100 tons; power 350 horsepower; speed 8 knots, shell 3 inches and 5 in the vital parts; Armament 2 15-inch (381 mm) Rodmans, muzzle-loading smooth, capable of launching a 500-pound (227 kilo) spherical bullet, mounted in a 10-inch (25.4 cm) armored turret

Fuente: http://members.tripod.com/~Guerra_del_Pacifico/monitores.html

6. Historia de la relaciones Internacionales de Chile, Don Adolfo Ibáñez Su gestión con Perú y Bolivia, Ximena Rojas Valdés, Editorial Andrés Bello, 1971, Santiago, páginas 74-75.

The project in question established the following:

Article No. 1: The President of the Republic is authorized to acquire one or two armored warships.

Article No. 2: You are also authorized to acquire a steamship capable of arming itself for war and assigning it to the service of the colony of Magallanes.

Article No. 3: You are finally authorized to raise a loan that produces two million two hundred thousand pesos, which will be used exclusively for the payment of the aforementioned ships.

Article No. 4: This authorization will last two years.

7. La Guerra del Pacifico, Gonzalo Bulnes, Tomo I “De Antofagasta a Tarapacá, Sociedad Imprenta y Litografía Universo, Valparaíso, 1911, página 36.

8. Historia de la relaciones Internacionales de Chile, Don Adolfo Ibáñez Su gestión con Perú y Bolivia, Ximena Rojas Valdés, Editorial Andrés Bello, 1971, Santiago, páginas 76-78.

9. In the book of Gonzalo Bulnes, Guerra del Pacifico, Tomo I “De Antofagasta a Tarapacá”, Capitulo II, emerge the details of the negotiations of said treaty appear.

10. La Armada de Chile: Desde la Alborada al Sesquicentenario (1813-1968), Rodrigo Fuenzalida Bade. Santiago, Chile: 1978, Empresa Periodística Aquí Está, Tomo III página 721. y La Guerra en el Pacifico Sur, Theodorus B.M. Mason, Editorial francisco de Aguirre, 1971, Argentina, páginas 33-36.

11. La Armada de Chile: Desde la Alborada al Sesquicentenario (1813-1968), Rodrigo Fuenzalida Bade. Santiago, Chile: 1978, Empresa Periodística Aquí Está, Tomo III, página 705.

12. Artículo Escuadra Chilena, 1879, A. Silva Palma.

Bibliography and Other Sources Consulted.

I. Historia de la relaciones Internacionales de Chile, Don Adolfo Ibáñez Su gestión con Perú y Bolivia, Ximena Rojas Valdés, Editorial Andrés Bello, 1971, Santiago.

II. La Guerra Entre España y las Republicas del Pacífico, Alfonso Cerda Catalán, Editorial Puerto de Palos, Chile.

III. La Armada de Chile: Desde la Alborada al Sesquicentenario (1813-1968), Rodrigo Fuenzalida Bade. Santiago, Chile: 1978, Empresa Periodística Aquí Está, Tomo III.

IV. La Guerra del Pacifico, Gonzalo Bulnes, Tomo I “De Antofagasta a Tarapacá, Sociedad Imprenta y Litografía Universo, Valparaíso, 1911.

V. La Guerra en el Pacifico Sur, Theodorus B.M. Mason, Editorial francisco de Aguirre , 1971, Argentina.

VI. Influencia del poder Naval en la historia de Chile, desde 1810 a 1910, Luís Langlois. Valparaíso, Imprenta de la Armada, 1911.

VII. Enciclopedia Monitor, Editorial Salvat, España 1972, Tomo XII página 4.806.

IX. Chilean Navy website.

http://www.armada.cl/p4_tradicion_historia/site/edic/base/port/tradicion_historia.html http://www.armada.cl/site/unidades_navales/156.htm http://www.armada.cl/site/unidades_navales/155.htm http://www.armada.cl/site/unidades_navales/163.htm X. Foro Fach-Extraoficial.

http://www.fach-extraoficial.com/portal/modules/news/ XI. Big Ships of the Peruvian Navy

http://es.geocities.com/peruwarships/index.htm XII. Some Historical Ships of the Marina de Guerra del Perú

http://www.geocities.com/perusovereign/buques.html XIII. Peruvian Historian Juan del Campo Rodríguez Webpage

http://members.tripod.com.pe/~guerra_pacifico/index.html http://members.tripod.com/~Guerra_del_Pacifico/guerra_pac.html http://members.tripod.com/~Guerra_del_Pacifico/monitores.html