Argentine Defense: From Independence to the Desert Campaign

Throughout Argentine history, national defense has suffered from not being treated as a state policy that transcends the ideologies and administrations of the ruling governments. This analysis, in three parts, examines the successes, failures, and outstanding issues in the evolution of Argentine defense.

Politics, Diplomacy, and War

In 1811, Paraguay declared its independence and outlined its territorial borders. However, these territorial claims conflicted with Brazil's, sparking a long period of tensions between the two countries, which eventually affected Argentina as well.

Over time, Paraguay also had commercial disputes with the Argentine government, leading to a tacit alliance between Argentina and Brazil, both of whom sought to protect their respective territorial and economic interests. Paraguay also faced difficulties trading in Uruguay, which led to tensions with Montevideo. By the end of 1864, Paraguay sent troops to Uruguay to support the Partido Blanco, which was fighting against the Partido Colorado, backed by Brazil.

Paraguay requested permission from Argentine President Bartolomé Mitre to move its troops through the Argentine Mesopotamia region on their way to Uruguay. This request was denied, but in April 1865, Paraguayan forces entered Argentina and occupied the city of Corrientes, forcing Argentina to join Brazil and Uruguay in war against Paraguay, a conflict later known as the War of the Triple Alliance.

This bloody conflict ended in 1870 with Paraguay’s surrender, causing severe territorial losses and demographic devastation, as nearly half of the Paraguayan population and about 90% of its men died.

The Paraguayan occupation of Corrientes could have been avoided if Argentina had better-equipped and strategically deployed armed forces.

Armed Forces and Sovereignty in Patagonia

After the independence of Argentina and Chile, both countries entered a period of rising tensions over their territorial claims in southern Patagonia. These tensions were further complicated by the rugged geography of the Andes Mountains, which made it difficult to accurately demarcate borders, and by the frequent raids carried out by the Mapuche tribes, who originated from the Chilean side of the Andes and often attacked Argentine settlements.

The Mapuches had gained territory in Patagonia and the southern Pampa region, displacing or exterminating local tribes, which increased Chilean influence in the area. Historians suggest that the loot from Mapuche raids—mostly stolen livestock—was sold in Chile with the tacit approval of local authorities.

Argentina, still embroiled in internal conflicts for nearly half a century since its independence, had not made significant advances in securing sovereignty over Patagonia. By the early 1870s, tensions between Argentina and Chile escalated, with both nations reaffirming their territorial claims. In 1872, Chilean authorities interfered with Argentine commercial activities in Santa Cruz, prompting the Argentine government to establish a military garrison in the region and explore the territory.

Tensions further escalated when, in 1876, Chile sent the corvette Magallanes to the port of Santa Cruz to seize a French ship that had been authorized by Argentina to extract guano. In response, the Argentine government dispatched a fleet under the command of Commodore Luis Py to Patagonia in 1878, with the mission of asserting Argentina’s sovereign rights over the region.

Given these tensions, President Nicolás Avellaneda informed Congress that, in legitimate defense, he had ordered Argentine warships to be stationed at the mouth of the Santa Cruz River and to fortify the area with artillery and troops. However, had there been a conflict, Argentina’s military forces would likely have been unable to defeat the Chilean fleet, which was simultaneously engaged in conflicts with Bolivia and Peru in the north.

The Desert Campaign and Affirmation of Sovereignty

In this context, with the nation’s territorial integrity at risk, General Julio Argentino Roca, then Minister of War and Navy, proposed to President Avellaneda the launch of a military campaign known as the Conquest of the Desert. The strategic objective was for the Argentine Army to advance southward to occupy Patagonia and reaffirm Argentine sovereignty over a region that, until then, had been under Mapuche control.

The Argentine government supported these military operations by establishing naval sub-delegations in Carmen de Patagones, Puerto Deseado, Río Gallegos, Isla de los Estados, and Ushuaia, which led to the settlement of the first Argentine communities in these regions, thus helping to consolidate national sovereignty in the south.

At the same time, the Argentine Army began to receive modern weapons (rifles, cannons, etc.) and the Navy acquired new warships (battleships and cruisers), positioning Argentina’s fleet as one of the most powerful in the world. These advancements allowed Argentina to reach a diplomatic resolution with Chile, culminating in the signing of the 1881 Boundary Treaty, which secured Argentine sovereignty over Patagonia.

In 1884, the Argentine Navy, under the command of Commodore Augusto Lasserre, deployed a fleet of six warships to Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados. During this mission, Lasserre encountered a British mission in Ushuaia. After a brief conversation, on October 12, 1884, the British flag was lowered and the Argentine flag was raised, reaffirming Argentina's sovereignty over the southernmost part of its continental territory, a date now considered the official founding of Ushuaia.

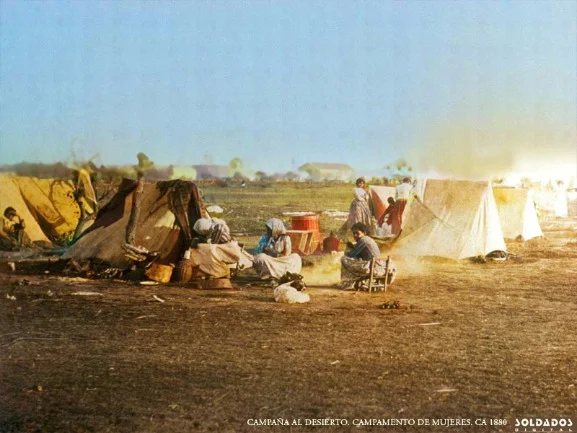

The Desert Campaign. Colección Servicio Histórico del Ejército.

Conclusion

Argentina's ability to defend its sovereignty in the south was heavily dependent on strengthening its armed forces. The development of a modern navy and a diplomacy backed by military strength were crucial in securing Argentine control over Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. The Desert Campaign, though controversial, was fundamental in consolidating Argentine control over vast southern territories, preventing territorial conflicts with Chile, and laying the groundwork for national defense in the late 19th century.