The Dirty 12 in Malvinas

𝗧𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝘄𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗽𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗼𝗻𝗲𝗿𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗠𝗮𝗹𝘃𝗶𝗻𝗮𝘀 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗮 𝗺𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗵: 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝘀𝘁𝗼𝗿𝘆 𝗼𝗳 “𝘁𝗵𝗲 Dirty 𝟭𝟮.”

They went down in history as a group of Argentine officers and non-commissioned officers who were held as prisoners by the British for up to a month after the war ended. They became known as “The 12 on the Gallows.” These were officers and non-commissioned officers from the three armed forces who had fought in the Malvinas and remained prisoners of the British on the islands until July 14, 1982 – one month after the surrender.

From the Army: Lieutenant Carlos Chanampa, Sub-Lieutenants José Eduardo Navarro and Jorge Zanela, First Sergeants Guillermo Potocsnyak, Vicente Alfredo Flores, and José Basilio Rivas, and Sergeant Miguel Moreno.

From the Air Force: Major Carlos Antonio Tomba, Lieutenant Hernán Calderón, and Ensign Gustavo Enrique Lema.

From the Navy: Corvette Captain Dante Juan Manuel Camiletti and Marine Command Principal Corporal Juan Tomás Carrasco. Ten of them were captured after the battle of Goose Green – between May 27 and May 29. The other two, Camiletti and Carrasco, were captured days later after they infiltrated enemy lines with an amphibious command patrol.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗼𝗹𝗱 𝗿𝗲𝗳𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗲𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗼𝗿

“I remember the day of the surrender. It was out in the open. The saddest moment of my life,” recalled José Navarro, who was a 21-year-old sub-lieutenant from Corrientes at the time, now a general, who had gone to war with the 4th Airborne Artillery Group. “I remember the incredible silence of 600 men standing in formation in a kind of square.” Those first bitter hours were even harder when, while housed in a sheep-shearing shed, they heard an explosion. They saw a British soldier who, “for humanitarian reasons,” as he excused himself, finished off a wounded Argentine soldier after a munition he was forced to carry detonated. “It was at that moment we said we wouldn’t work anymore. I think we were the ones who started pickets in the country.” The war was over, but in some way, it continued. In San Carlos, they were locked up in a three-by-two-meter room in the old refrigerator, which had an unexploded 250-kilo Argentine bomb embedded in one of its walls. It still had its parachute. In the mornings, they lined up to receive a thermos with tea and biscuits. Since they had no mugs, they had to go to a nearby dump to find cans, which they washed with seawater. They slept on the floor, dressed, curled up, wearing their berets. The bathroom situation was even worse. In one corner of that small space, there was a 200-liter can cut in half. When someone used it, the others had to turn around until they managed to get a blanket to improvise a screen. Every so often, they had to take the can to empty it by the sea. During the time they were held, they were moved from one place to another. One day, they were boarded onto the Sir Edmund. “You’re returning to Argentina,” they were told. But it wasn’t true. Like in the movies, Navarro was interrogated in a cabin, blinded by a powerful light. An English interrogator, who spoke very formal Spanish, bombarded him with questions: How had he arrived on the islands? Where had the artillery in Darwin come from? And the question that obsessed the British: “Did you know there were war crimes in San Carlos?” The British were looking for Lieutenant Carlos Daniel Esteban, who was suspected of having shot down a helicopter they claimed was carrying wounded. They never realized that Esteban was housed on the same ship. They never found him. Navarro was taken back to the refrigerator and locked in a six-by-five-meter refrigeration chamber with cork walls. It had only one door, with a broken window to let in air. A light bulb hanging from the ceiling was the only source of illumination.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗯𝗶𝗿𝘁𝗵 𝗼𝗳 “𝘁𝗵𝗲 Dirty 𝟭𝟮.”

They were left alone for days, with no questioning, which caused them to lose track of day and night. Due to the heat, they stayed in their underwear and once again had to use the filthy 200-liter can. After a day and a half without food, they were finally given something to eat, though they never knew if it was stew or chicken soup. They were hungry but had no utensils. Major Carlos Tomba was the first to act, saying, “I’m eating with my hand,” and the others followed suit. On another trip to the dump, they scavenged spoons and cans. Later, they were taken aboard a ship. When they heard the English national anthem playing over the loudspeakers, mingling with cheers of joy, they realized everything was over. It was June 14. The English captain confirmed it when he approached them to offer some words of encouragement.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗳𝗹𝗮𝗴, 𝗮 𝘁𝗿𝗼𝗽𝗵𝘆 𝗼𝗳 𝘄𝗮𝗿.

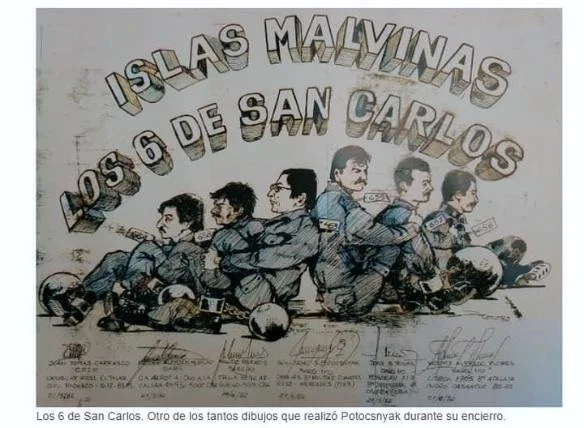

Navarro recalled that at that point, security relaxed so much that Corvette Captain Dante Camiletti came up with the wild idea of taking over the ship. However, while the English showed little concern for their prisoners, they were visibly wary of Argentine aviation, especially the Exocet missiles. On the Sir Edmund, they were on their way back to the mainland when Navarro entered a random cabin and took an English flag. “You idiot!” his companions scolded him. They managed to hide the flag inside a panel in the cabin ceiling before the English, frantically searching every corner of the ship, discovered it. When Navarro stepped onto the dock in Puerto Madryn, he showed the English the flag, which he still has framed along with copies of the famous drawings made by Potocsnyak, one of his fellow prisoners. “Do you know what it means to surrender on Army Day?” asked the Santa Fe-born Guillermo Potocsnyak, known as “Poto” or “Coco” for his hard-to-pronounce Croatian surname. A stout senior sergeant who had gone to the islands as a first sergeant with the 12th Infantry Regiment, he later became a local hero.

𝗔𝗻 𝗮𝗿𝘁𝗶𝘀𝘁 𝗮𝗺𝗼𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝘁𝘄𝗲𝗹𝘃𝗲

After fighting at Goose Green and San Carlos Bay, Potocsnyak was captured. While helping collect bodies of fallen Argentines, he stumbled upon a frozen body that suddenly blinked. He placed the soldier on the hood of a carrier, and although the soldier lost a leg, Potocsnyak saved his life. A popular figure among his peers and even his captors, Potocsnyak had a knack for drawing. He traded chocolates and cigarettes for paper, pencils, and pens, and his drawings began circulating, crossing all boundaries. Many of them, he says, are likely in the United Kingdom today. He’s the author of the famous sketch of the 12 officers who were held until July 14. In the foreground is Tomba, clearly wearing a fanny pack that they all wore as life vests. Even after June 14, the British hadn’t ruled out Argentine air attacks. On seeing the drawing, someone—he couldn’t remember who—suggested, “Call it ‘The 12 on the Gallows.’” It references the title of a 1967 war movie where a dozen dangerous prisoners were assigned a risky mission in German territory during World War II. Potocsnyak remembers that from time to time, the English would subject them to searches with batons while they had to stand facing the wall. When he told an Englishman, “Shove that baton up your…,” the Brit responded, “Don’t play smart; I speak Spanish better than you.” In the postwar period, Potocsnyak lost his wife, but years later, while studying Croatian—he has dual nationality—he met his second wife. “Family was my first support,” he admitted. He has two children and four grandchildren. He studied to become a history teacher, not to teach but “to understand what we went through there, and also as a way to feel useful.” His life as a veteran wasn’t easy. He had to leave Córdoba, where he lived, because people always asked him about the war, and he felt he couldn’t turn the page. Time eventually helped him move on. Of that famous group of 12, he highlights that “Major Tomba is a true gentleman, an extraordinary person.” After Corvette Captain Dante Camiletti, Major Carlos Tomba—the highest-ranking officer and a 36-year-old from Mendoza who had fought as a Pucará pilot—assumed leadership of this diverse group. Now a retired brigadier, Tomba lives in Mendoza, where his last name holds historical significance in the province. His first clash with his captors came over defending his belongings—his helmet and leg straps from his ejection seat. He managed to keep them, along with pajamas given to him by his wife. The helmet and leg straps are now on display at the Air Force Museum in Córdoba. He recalls that the early days were the hardest: 48 hours without water, followed by a can of pâté. Unsure of what the next day would bring, they only ate half of the can’s contents each time. As the group’s English speaker, he acted as their spokesperson and interpreter with the British doctor who treated the wounded Argentines. He also negotiated to remove the 200-liter can from their tiny room and managed to have their meals served according to the local time, not British time. Tomba saw boxes of missiles labeled “USAF” from the U.S. Army. He focused on keeping his mind active; they had no idea what was happening on the islands and didn’t want to waste energy, as they often felt faint from the lack of food. He even devised an escape plan, thinking he’d found a weak point in the guards’ security. One night, he climbed a wall intending to slip away in the dark, but a blow to the mouth brought him back to reality. He recalls some laughable situations, like the day 40 of captivity. They were in San Carlos, and for the first time, they were allowed to bathe. They were made to strip, each given a towel, and ordered to run 200 meters to a shack, where an Englishman on the roof poured hot water on them.

“𝗗𝗼 𝘄𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝘆𝗼𝘂 𝗰𝗮𝗻.”

In 1982, Chanampa was a 27-year-old lieutenant. From Villa Dolores, where he now lives, he recalled that when they surrendered, they were exhausted and conveyed this to the English, who then made them dig latrine pits and collect munitions. He is critical of the war’s leadership. He couldn’t believe what he was told when he asked for vehicles to move artillery pieces to hinder the British advance: “I have nothing to tow the cannons with.” The reply was, “I don’t know, get horses, do what you can.” They received orders that were impossible to carry out. In the early days as a prisoner, he slept alongside other Argentines on makeshift cots made from ammunition boxes. He was interrogated twice, once at the refrigerator in San Carlos and a second time in a sheep pen separated by a stream, where they were taken on a gloomy morning in a rubber boat. They were made to undress in the open air, interrogated, dressed again, and returned. However, Chanampa noted that the English knew every detail of the Argentine positions and their real capabilities. He was also struck by the youth of many British soldiers and that some officers he spoke with showed little interest in the war. He said that when morale was low among the group, they would read aloud letters some comrades had saved from family members. Chanampa was one of the many who had to start from scratch multiple times. He worked in commerce, became a textile company manager, and later a director in an insurance company. In Villa Allende, he seems to have found his place in the world.

𝗣𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗼𝗻𝗲𝗿𝘀 𝗼𝗻 𝗔𝘀𝗰𝗲𝗻𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗜𝘀𝗹𝗮𝗻𝗱?

Five hundred kilometers from Villa Allende lies the town of O’Brien, named after an Irishman who risked his life for Argentina in the independence wars. There was born Jorge Gustavo Zanela, who, at 23 and with the rank of sub-lieutenant, went to war with the 4th Artillery Group as part of Task Force Mercedes. When he was captured, like many others, he was taken in a Chinook helicopter to San Carlos. While in the refrigerator, he grew hopeful when they told him they were taking him to Uruguay, but at the last moment, he was taken off the ship along with other officers, selected based on seniority and specialty. Zanela still keeps under the glass of his desk a Red Cross certificate for his transfer to Ascension Island, a transfer that never happened. He was interrogated by an Englishman with a military interpreter from Gibraltar who insisted on knowing about Argentine positions and obtaining maps.

𝗘𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 𝗽𝗼𝘂𝗻𝗱𝘀 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗲𝘅𝗽𝗲𝗻𝘀𝗲𝘀

Zanela has vivid memories of the wounded English soldiers affected by the Argentine air attack on Fitzroy Bay, many of whom suffered severe burns. June 8, considered the blackest day for the British fleet, saw Argentine planes sink three ships, damage a frigate, and leave 56 British soldiers dead and 200 injured. He remembers that “the 12 on the gallows” were on a ship crossing the English Channel. Representatives from the Red Cross, mostly Uruguayans and Spaniards, would occasionally visit them. They would even argue with the English, taking down their information as prisoners of war and carrying letters for their families, which were sent through Switzerland. Like other prisoners, they were given eight pounds for expenses, though they spent only a small amount, saving the rest as a memento of the war. Toward the end, they managed to get a radio and learned about Pope John Paul II’s visit. The English themselves informed them of Argentina’s elimination from the World Cup, celebrating loudly when Argentina surrendered.

Zanela did not join the main group of prisoners taken to Puerto Madryn. Instead, he remained in San Carlos with other officers as the Argentine Air Force continued to pose a threat, initially refusing to observe the ceasefire. Finally, on July 14, they were moved to Puerto Argentino and boarded the Norland. Once back on the continent, they were forbidden from speaking. In Trelew, they received clean clothes, and after several layovers, an Army plane brought them to their unit in Córdoba.

Now Colonel Jorge Zanela heads the Office of Veterans Affairs for the Malvinas War. His office in Palermo resembles a small museum dedicated to his time in the South Atlantic conflict. On one wall, there’s a yellowed copy of the sketch of “the 12 on the gallows.” In 2015, he returned to the islands and visited the refrigerator, now abandoned and in ruins, where the hole left by the undetonated Argentine bomb remains. He wasn’t allowed to enter due to the danger of collapse. Over the years, the group has never reunited. Lieutenant Hernán Calderón passed away on March 24, 1983, in a training flight accident, and First Sergeant José Basilio Rivas died in a car accident on December 22, 2001. Some of the twelve retired shortly after, while others continued their military careers. But they never stopped being part of “the Dirty 12.”