The people of Bahía Blanca take to the streets to celebrate the triumph of the Revolution.

Aftermath

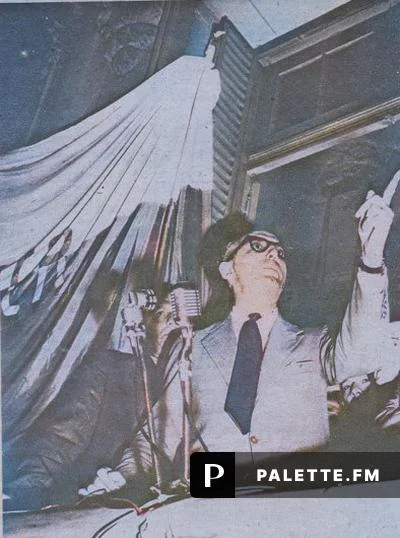

Joy and happiness in the crowd after Perón resignation

Thus concluded the first Argentine armed conflict of the 20th century, which, in just seven days of fighting, claimed the lives of nearly a thousand people. The casualties included civilians and soldiers—men, women, children, and the elderly. The majority of the deaths occurred on June 16 during the bombing of Buenos Aires, when 229 victims were identified in hospitals, clinics, and public aid facilities. However, the true death toll was far higher, as Dr. Francisco Barbagallo notes in Daniel Cichero's Bombs Over Buenos Aires. The chaos was so overwhelming that tracking the countless bodies transported by ambulances and trucks became impossible.

To grasp the scale of the attack, it is worth noting that 14,000 kilograms (14 tons) of explosives were dropped that day—half the amount used in the bombing of Guernica—yet the death toll was nearly equivalent to that of the Spanish city.

On that day, 43 rebel aircraft carried out the assault: twenty North American AT-6s, five Beechcraft AT-11s, three Catalinas, one Fiat G-55A Centauro reconnaissance aircraft dispatched to Rosario to contact General Bengoa, and ten rebel Gloster Meteors. Additionally, four aircraft initially refused to counter the attack but later joined the rebellion. Including loyalist aircraft, the total number of planes involved exceeded fifty.

Celebrations in Bahía Blanca

On June 16, 1955, the Air Force and Naval Aviation took their first baptisms of fire; the first two shoot-downs in the national aeronautical history occurred when the AT-6s of midshipmen Arnaldo Román and Eduardo Bisso were hit by the enemy, the first by shrapnel from the Gloster Meteor of Lieutenant Ernesto Adradas over the Río de la Plata and the second by anti-aircraft guns from the 3rd Regiment of La Tablada in the town of Tristán Suárez, Buenos Aires, not counting the Gloster that, due to lack of fuel, crashed into the waters of the Plata, between Carmelo and Colonia. That day also saw the first shoot-down carried out by a jet on the American continent (that of midshipman Romás by Lieutenant Adradas) and the entry into action of the tanks when a Sherman of the Motorized Regiment “Buenos Aires” fired on the Ministry of the Navy.

Victorious leaders. From left to right: CN Arturo Rial, Dr. Clemente Villada Achaval, General Julio A. Lagos, General Eduardo Lonardi, General Dalmiro Videla Balaguer and Commodore Julio César Krausse

Buenos Aires became the first (and so far, only) capital in South America to endure a large-scale aerial bombardment, joining the ranks of only a few cities worldwide to have suffered such an attack. It shares this tragic distinction with Gibara in Cuba, bombed by President Machado's air force in 1931, and Puerto Casado in Paraguay, targeted by the Bolivian Air Force in 1933. However, both of these events pale in comparison to the scale of the bombardment in Buenos Aires.

During the attacks, numerous locations in the city were hit, with the main targets including the Government House, Plaza de Mayo, the National Mortgage Bank, the Ministry of Finance, the Army Ministry (Libertador Building), Hotel Mayo, the Central Police Department, the CGT headquarters, the Ministry of Public Works, the Patagonia Import and Export Company, various buildings along Av. Paseo Colón, the service station of the Argentine Automobile Club, and the presidential residence at Unzué Palace.

Additionally, La Tablada suffered heavy damage as the 3rd Infantry Regiment was strafed and bombed on Av. Crovara and Av. San Martín while marching toward the city center. The Ministry of the Navy was also struck during an attack by Army units, and the Banco Nación was hit as revolutionary civilian commandos took refuge on its rooftop.

On September 16, Argentina witnessed its first air-naval battle when the Peronist Air Force engaged the Ríos Squadron. Mar del Plata was also bombed, initially by a lone naval aircraft and later by Navy ships targeting large coastal oil deposits, the Submarine Base, Army positions on a nearby golf course, and the Camet Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiment.

Three days later, the submarine Santiago del Estero entered combat for the first time, using its 40 mm Bofors cannon to fire on unidentified aircraft near Montevideo. The towns of Saavedra and Río Colorado also fell victim to aerial bombardments during this period.

The Plaza de Mayo is packed, cheering on the Revolution that overthrew the tyrannical president

Rear Admiral Toranzo Calderón upon arriving at the Municipality of Bahia Blanca

On September 21, 1955, as the final acts of the conflict concluded, an atmosphere of anticipation lingered across the country. While government emissaries and representatives of the rebel forces engaged in negotiations, combat units in Córdoba began their gradual return to base.

That same day, news of the revolutionary forces’ victory spread, prompting the people of Córdoba to flood the streets in celebration of the regime’s fall. Crowds gathered at Plaza San Martín, in front of the ruined Cabildo building, adorned with three Argentine flags, cheering for the leading figures of the rebellion. Thousands of men and women entered the adjacent Cathedral to give thanks to the Lord and the Holy Mother for the end of the conflict. Meanwhile, a jubilant procession of cars, motorcycles, trucks, buses, and pedestrians filled the streets, chanting in support of the revolution, its leaders, and the nation’s heroes.

Two days earlier, Bahía Blanca had erupted in similar enthusiasm. Residents filled the streets, cheering, singing, and waving flags while wearing sky-blue and white ribbons and rosettes. Portraits of San Martín, Belgrano, and Our Lord Jesus Christ were prominently displayed. Outside the CGT building, crowds sang the National Anthem, symbolizing the defiance of the fallen regime, and applauded Admirals Toranzo Calderón and Olivieri as they arrived at Bahía Blanca’s municipal headquarters after their release from detention in La Pampa. In front of the burned-out offices of the Democracia newspaper and the Bernardino Rivadavia Public Library, the crowd shouted, “Death to Perón!” and “Long live the Fatherland and Liberty!”

Toranzo Calderon in the Municipality of Bahia Blanca

On September 21, back in their respective units and after a refreshing hot bath, cadets and conscripts from the Military Aviation and Airborne Troops schools in Córdoba were informed that the next day they were going to participate in the parades that had been held to commemorate the victory.

On the 22nd, very early in the morning, the soldiers formed up in the courtyards of both schools to head into the city to parade with the Army troops and civilian commandos who had taken part in the battle. The Cadet's Diary is graphic in recounting the events.

"The unit remains in the same condition as always... All the officers gathered with General Lonardi at the Cadet Casino, which is why we couldn’t contact F... to request a replacement. When we finally managed to, he told us there was only one tent left with a cadet and 16 soldiers. We worked like mad to take down the tents and move them to the Squadron. Once we finished everything, we went to the unit, and there, among the three group leaders, the 'exciting' draw took place to decide who would stay... If it had been me, I would have had to muster a great deal of willpower to remain, but luck was on my side; of course, it fell to the 'Turk.' Poor guy, he won’t be any better off than I am."

Rear Admiral Samuel Toranzo Calderon arrives in Bahia Blanca

Thus, the troops boarded military trucks and buses and headed toward the provincial capital where, upon reaching Av. Vélez Sarsfield, they dismounted to begin the parade. They did so after a long wait, in front of the population who cheered them and threw flowers at them while a shower of papers fell from nearby buildings to the cry of “Freedom! Freedom!” which could be heard everywhere.

After the parade, the troops returned to the barracks to continue their activities during peacetime, unaware that the following day would claim the life of another comrade.

During a patrol and observation flight, the Calquin I.Ae-24 of the 2nd Attack Group, piloted by Second Lieutenant Edgardo Tercillo Panizza, crashed on the outskirts of the city due to mechanical problems.

Officers welcome their boss after his release

Once they had heard of this, cadets and officers headed towards the site, first crossing the Aeronautical District, with the intention of seeing the remains of the aircraft that was still smoking on the field. Once there, they came across the remains, observing them in silence while meditating on the events that had taken place in the previous days and the course that history would take from that moment on.

Mar del Plata also joined in the celebrations with long human columns parading through its streets to the City Hall, to sing the National Anthem and wave flags.

On September 23, the fronts of the city woke up decorated with the colors blue and white; around 10:00 there was a new march to the government palace where rosettes, ribbons and flowers were distributed as in the days of May and the celebrations continued in different places until late at night.

Argentina was beginning a new path; An era had ended and another had begun, but the disagreement between brothers was not going to end there. The country would never find its way again and society would continue to crumble to unsuspected limits.

Notes

[1] Gargiulo was the creator of IMARA (Argentine Marines), infusing the spirit of the US Marines into their training and enlistment..

Photos: Miguel Ángel Cavallo, Puerto Belgrano. Hora Cero. la Marina se subleva

1955 Guerra Civil. La Revolucion Libertadora y la caída de Perón