The Malvinas conflict reached its conclusion on June 14, marked by intense hand-to-hand combat, heroic resistance, and the British apprehension towards Argentine aviation.

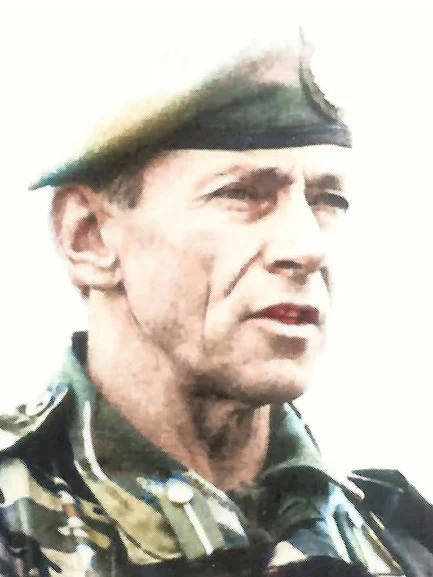

During the final hours, tense negotiations took place between the Argentine and British forces. General Galtieri issued orders to Menéndez, which were met with defiance. The British harbored bitterness over the relentless air attacks they faced and the battles that etched themselves into history as some of the most valiant displays of courage exhibited by the Argentine troops. General Mario Benjamín Menéndez was the governor. In this photo he addresses troops in Darwin on May 25, 1982. (AP)

General Mario Benjamín Menéndez was the governor. In this photo he addresses troops in Darwin on May 25, 1982. (AP)During the initial days of June, the English initiated efforts to establish a ceasefire, using the radio telephone at the "King Edward" hospital, a facility frequently used by the islanders for medical consultations. On June 6, a call was answered by Dr. Alison Bleaney, who was initially skeptical and almost dismissed it as a prank. However, it turned out to be a British staff officer trying to communicate with the Argentine authorities.

Dr. Bleaney relayed the message to Commodore Carlos Bloomer Reeve, the Secretary General of the Interior, through a messenger. Governor Mario Benjamín Menéndez was then informed of the communication, and he appointed Navy Captain Barry Melbourne Hussey to listen to the British message without answering any questions. The message from the British was an attempt to find common ground for ending the hostilities.

Both parties agreed to communicate daily at 1:00 p.m. until the 12th of June.

The final hours of the war are renowned for showcasing the

greatest display of Argentine resistance.

Mount Longdon was the scene of a dramatic combat by soldiers from the 7th Regiment. (AFP)

Mount Longdon was the scene of a dramatic combat by soldiers from the 7th Regiment. (AFP)Starting from June 9, the British intensified their artillery fire. Subsequent battles occurred between the 11th and 13th at strategic locations, namely Mount Harriet, Mount Longdon, Two Sisters, Mount Tumbledown, and Wireless Ridge. These battles formed the final defensive line before reaching Puerto Argentino.

During the combats at Mount Harriet and Mount Two Sisters, the British forces encountered formidable resistance. A skilled sniper managed to impede the advance of a Royal Marines company for hours, while another company from the 45th also faced significant opposition on the slopes of Two Sisters. The tenacious resistance demonstrated by the Argentine troops earned admiration from the enemy.

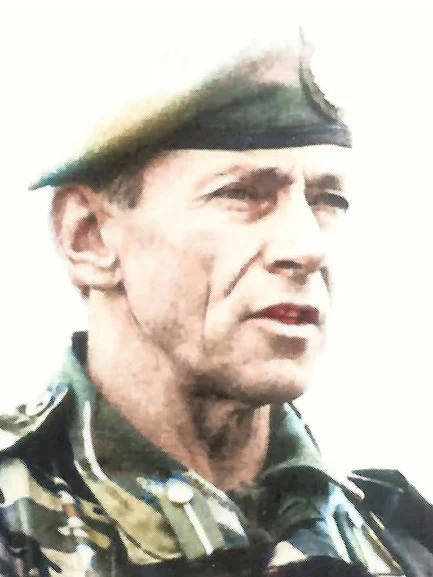

Jeremy Moore, the British commander. The day before the surrender he saved his life in an air raid.

Jeremy Moore, the British commander. The day before the surrender he saved his life in an air raid.

A grueling battle took place on Mount Longdon, resulting in a significant number of casualties. The British forces had to push forward with fixed bayonets, and once they reached the summit, they had to defend against two Argentine counterattacks. The 7th Regiment's C Company, consisting of a platoon of 46 men, forced the English B Company into a withdrawal.

The severity of the conflict was evident in the numbers:

out of the 278 men in the "Maipú" Company, only 78 managed to withdraw after enduring twelve hours of combat against the 3 PARA. The British forces suffered 23 killed and 70 wounded.

On Saturday, June 12, at half past 3,

history witnessed the launch of an MM-38 Exocet missile from a ramp near the Puerto Argentino airport. The missile was directed at HMS Glamorgan, a British ship responsible for nightly bombardments of the capital. The shot proved successful, hitting the ship's deck and rendering its electronic devices inoperative.

The Tumbledown combat, June 13, 1982. Painting by Steve Noon, British artist.

The Tumbledown combat, June 13, 1982. Painting by Steve Noon, British artist.On the 13th, approximately twenty air missions were conducted over British positions. During an air raid on his camp at Mount Two Sisters, Commander Jeremy Moore miraculously escaped with his life.

On the same night, around 50 Scottish soldiers launched an attack on the base of Mount William, leading to an order for the Argentine defenders to withdraw. Additionally, a British speedboat raid on the Camber Peninsula, north of the Puerto Argentino roadstead, was repelled before midnight.

In the early hours of June 13, a section of the Amphibious Engineer Company withdrew from the northwest of Mount Tumbledown and headed towards the command post of Marine Infantry Battalion 5. At three in the morning, amidst a snowstorm, a fraction of them, along with members of the Amphibious Engineer Company and a section of riflemen from the Company of the 6th Infantry Regiment, prepared to counterattack the west side of Mount Tumbledown. Two hours later, the Nácar Company attempted to regain control of the mountain. A counterattack ensued, resulting in half a dozen Scotsmen being wounded. However, facing heavy enemy fire, General Menéndez authorized the withdrawal of the forces.

Pilots, mechanics, technicians and soldiers of the M5 Dagger Squadron before one of the missions in Comodoro Rivadavia. The actions of the Air Force and Naval Aviation pilots were the greatest concern of the British.

Pilots, mechanics, technicians and soldiers of the M5 Dagger Squadron before one of the missions in Comodoro Rivadavia. The actions of the Air Force and Naval Aviation pilots were the greatest concern of the British.During the battle of Wireless Ridge, the

7th Regiment's trenches endured a relentless onslaught of nearly 6,000 shells fired by British artillery. Initially, the English forces took control of the northern sector, and two companies, which had been engaged in combat since the previous day, made their way towards Moody Brook while facing the relentless barrage of British cannons.

Despite the valiant efforts of the Argentine troops to hold their ground, the British advance persisted. With the support of light tanks, the British infantry managed to reach their positions and encircle the troops from BIM 5. On the southern slope of Wireless Ridge, approximately 40 men from A Company of Regiment 3 courageously launched a counter-attack against soldiers from Para 2.

As dawn broke on the 14th, the surviving soldiers from the battle at Wireless Ridge regrouped

and formed a defensive line near Felton Creek. About

50 survivors from the 7th Regiment launched a counter-attack against Moody Brook Barracks, which was already under British control. However, they were met with fierce artillery fire and had to retreat.

The British were impressed by the resolute attitude displayed by the Argentine forces. Some of the soldiers of Regiment 3 who staged one of the last counterattacks of the war.

Some of the soldiers of Regiment 3 who staged one of the last counterattacks of the war.The Air Force executed its final mission: deploying two Canberra and two Mirage bombers to attack British positions at Furze Bush Pass. Tragically, one of the Canberras was shot down during the operation.

At 6 o'clock in the morning, the Argentine artillery opened fire towards the top of Wireless Ridge, aiming to halt the advance of the British paratroopers. The artillery provided cover fire to facilitate the retreat of the Argentine soldiers. An hour later, the British forces gained control of Tumbledown, and helicopters fired missiles at the Argentine artillery near Moody Brook.

Amidst the withdrawal, a second lieutenant and 21 gunners from the 4 Airborne Group remained behind to operate the last piece of artillery, which they used to engage British paratroopers. However, they were forced to withdraw when a shell got stuck.

At that moment, Carlos Robacio, the commander of BIM 5, defied two withdrawal orders and continued fighting.

In the war's final engagement, a section of the Sea Company from BIM 5 successfully disabled two British Sea King helicopters. BIM 5 completed its withdrawal by 3:00 p.m., marching at an accelerated pace through the streets of Puerto Argentino, with the troops remaining in possession of their weapons. They aimed to regroup and prepare for urban combat.

Commander Carlos Robacio was the commander of the 5th Marine Infantry Battalion. On more than one occasion, he rejected the withdrawal order.

Commander Carlos Robacio was the commander of the 5th Marine Infantry Battalion. On more than one occasion, he rejected the withdrawal order.In his memoirs, Admiral

Woodward recounted the dire situation during the war's final days: "

We were stretched to the limit, with only three ships - Hermes, Yarmouth, and Exeter - functioning without major operational issues. 45% of our destroyers and frigates were incapacitated. The Andromeda's Sea Wolf was disabled, all the Brillant systems had various defects, and the Broadsword had one and a half weapon systems functioning, with one propulsion shaft permanently damaged. None of the 21 ships were fit for battle: the Avenger and Arrow were broken, and Olimpus turbines disabled, among other issues.

It was a crumbling fleet."

"

In this beautiful place, we have only one Sea Dart line of fire to protect the Etendards. Our convoys to and from the coast are 'escorted' by a semi-paralyzed frigate. The gun line, once consisting of four ships, is now down to two due to damages. The towing, repairs, and logistics area is 'protected' by the broken-down Glamorgan, and South Georgia is valiantly defended by the poor, broken-down Antrim and the formidable battleship Endurance."

The withdrawal of BIM 5 from Sapper Hill marked the end of General

Jofre's planned resistance. Most factions abandoned their positions, walking towards Puerto Argentino,

some alongside British soldiers who allowed them to retain their weapons.Para 2 commanded Wireless Ridge, Para 3 Mount Longdon, 42 Commando Mount Harriet, and 45 Commando Two Sisters. The Scots Guards controlled Tumbledown, the Gurkhas were on Mount Williams, and the Welsh on Sapper Hill, with Puerto Argentino dominated by two English brigades.

Generals

Menéndez and Jofre agreed that continuing the fight would only lead to more loss of life. Jofre stated, "This is not enough."

In the midst of a conversation with

General Leopoldo Galtieri, the call was abruptly cut off by an English bombardment. Galtieri, at Casa Rosada, remarked,

"It seems that Menéndez is giving up..." and asked to speak with him.

Menéndez's assistant was sent to communicate with the English troops and seek a ceasefire agreement.

Galtieri called again,

demanding loudly that the soldiers leave their foxholes and counterattack. Menéndez explained that he lacked sufficient support, particularly from naval and air forces. Despite

Galtieri's insistence to counterattack using troops from the 3rd and 25th regiments and the marine infantry, Menéndez refused, knowing the futility of such an action. Galtieri warned him that he would have to answer for his decision upon returning to the continent. Menéndez considered

invoking United Nations Resolution 502, which called for Argentina to cease hostilities, withdraw troops, and negotiate, but Galtieri objected. Faced with difficult choices, Menéndez decided to

"leave with honor."A Gazelle helicopter from Fearless took off, carrying British Parliamentarians. They tied a white parachute cloth to its belly. The officers

Bell,

Reid, and a Spanish-speaking radio operator accompanied them.

As they walked towards the seat of government,

Menéndez awaited them at the door. In the talks, Captain Melbourne Hussey was joined by Vice Commodores Carlos Bloomer Reeve and Eugenio Miari, a specialist in international treaties.

During the first meeting,

the British expressed concern about Argentine aviation and called for their attacks to cease.

Until the last moment, Galtieri demanded that Menéndez counterattack with the forces available. He also did not want the governor to sign any documents. (Telam)

Until the last moment, Galtieri demanded that Menéndez counterattack with the forces available. He also did not want the governor to sign any documents. (Telam)At 11 a.m., as snow began to fall, a ceasefire was reached. For the British, this was a stroke of luck as the troops who attacked Puerto Argentino

were left with only six batches of ammunition; the rest had sunk with the Atlantic Conveyor.

Galtieri laid out his conditions:

Menéndez should not sign any document, and the discussions should revolve around evacuation rather than surrender. Each man was expected to return in uniform, with his weapons, and the commitment was to be upheld with honor. Menéndez was taken aback by the order not to sign, knowing it would be an impossible request to fulfill.

Moore

y Menéndez acordaron el alto el fuego. El gobernador exigió quitar la

palabra "incondicional", de los términos de la rendición.

Moore

y Menéndez acordaron el alto el fuego. El gobernador exigió quitar la

palabra "incondicional", de los términos de la rendición. Each party retreated to confer with their superiors and agreed to reconvene later, this time with their respective leaders, during the night.

At 19:45, Jeremy Moore, the British forces commander, arrived by helicopter, visibly perturbed by the snowstorm they had to navigate through. He was accompanied by seven officers from his General Staff, the radio operator with direct communication to London, and a legal officer.

In one hand, he held a document outlining the terms of surrender, and in the other, a bottle of whiskey.

The Argentinians declined

to sign an "unconditional" surrender; they insisted that there would be no public surrender ceremony, that the officers would retain command over their troops, and they would keep their flags.

Moore's telegram announcing that it was all over.

Moore's telegram announcing that it was all over.

Moore's main concern revolved around the airmen. The aviation action had resulted in the loss of 7 British ships, with 5 being rendered inoperative and 12 experiencing mechanical breakdowns. In response, they reached out to Brigadier Ernesto Crespo, who had proclaimed at the start of the war:

"If anyone thought that the phrase 'defend the Homeland until losing your life' was merely rhetoric, this is the moment of truth." As the head of the air command, Crespo pledged to comply with the cessation of hostilities,

although he made it clear that he was not surrendering.

After removing the word "unconditional" from the document and obtaining assurances from the air command, all obstacles were overcome. Menéndez then initialed the document, followed by Moore and a British officer as a witness.

Cover of the Clarín newspaper that gave an account of the ceasefire on the islands.

Cover of the Clarín newspaper that gave an account of the ceasefire on the islands.

The ceasefire would begin at 23:59 on June 14. Menéndez requested authorization to meet with his General Staff but it was denied, informing him that he would shortly be transferred to “Fearless” as a detainee.

The war was over.Sources:

La guerra inaudita. El conflicto del Atlántico Sur, de Rubén Oscar

Moro; 1982. Los documentos secretos de la guerra de Malvinas/Falklands y

el derrumbe del proceso, de Juan B. Yofre; Los cien días. Las memorias

del comandante de la flota británica durante la guerra de Malvinas, de

Sandy Woodward; Una cara de la moneda. La guerra de Malvinas according tothe complete version of The Sunday Times Insight Team de Londres; newspaper from June 1982.