Malvinas: A Study CaseComes from

Part 1 - follows with

Part 3

Part 2/3

By

Harry Train,

Admiral USN

Critical analysis of the Malvinas Conflict. It covers chronologically from the previous incidents to the end of the battle for Puerto Argentino. Strategically, it includes the levels of general, military and operational strategy. The analysis considers the concepts of the operation from the perspective of each side.

Argentine Directives for Action

The Argentine directives for action stemmed from the Junta's erroneous hope of achieving a diplomatic solution. The directive for the recapture of the Malvinas on April 2 established, "do not spill British blood or damage British property." Between April 2 and April 30, the directives were "fire only if attacked." When operational commanders were observed by the Junta for issuing orders that violated this directive, such orders were annulled. One example was the Junta's revocation of the naval operations commander’s order for the ARA Drummond and ARA Granville to intercept the Endurance if it evacuated workers from South Georgia. Another example was the withdrawal of authorization for the ARA San Luis submarine to use its weapons when ordered to enter the exclusion zone. The ARA San Luis patrolled the exclusion zone from April 20 to April 30 without authorization to use its weapons.

The authorization to use weapons was granted to Argentine forces on April 30. At that time, Argentine forces were informed that any ship in the exclusion zone should be considered British. This order did not account for the fact that Russian fishing vessels were present in the exclusion zone. Decision-making authority over directives for action was as tightly held at the highest political levels in Argentina as it was in the United Kingdom.

British Directives for Action - Political Structure in London

The War Cabinet created a Directives Committee comprised of officers tasked with making forecasts and providing commanders with the directives they needed, in a manner that could be perfectly understood. This committee met daily at 1800 hours and addressed questions such as what authorizations were to be granted when the Task Force crossed the equator or what prior approval long-range maritime patrol aircraft required if encountering Argentine forces. The committee’s decisions were always approved because they anticipated events.

The maritime exclusion zone defined an area where British ship commanders and pilots could attack. It was an area where the Argentine command knew their units would be attacked. This zone was intended, or so it was thought, to provide British commanders with a sufficiently deep buffer area to avoid tactical surprises for the Task Force ships, which lacked tactical reconnaissance aircraft and high-performance planes.

The next step in the evolution of directives for action and the maritime exclusion zone was the declaration of a Total Exclusion Zone on April 30. A complication arose on April 23 when the order for free use of weapons was issued. This applied everywhere, against any force deemed a threat. A warning that this order had been issued was broadcast at the time. The maritime exclusion zone remained unchanged.

In the conflict theater, British directives for action contained a numbered list of rules covering foreseeable situations, target descriptions, and the zones where the rules applied. These rules—of which there were many—were implemented selectively in time and place according to political and military advice. The fundamental purpose of the directives for action was to provide political and military information to commanders in the theater of operations, with established rules when a policy of maintaining the status quo, de-escalation, or escalation was required. The numbered directives still carried ambiguities and frequently required interpretation via satellite communications. The definition of "hostile intent," given the existence of weapons requiring rapid reaction—such as the Exocet—created problems ultimately resolved by defining "hostile intent" as the mere physical presence of an Argentine platform.

The British also amended directives for action to authorize attacks on any unconfirmed submarine contact operating near their own forces. Crucial to the structure and execution of directives for action were the 200-nautical-mile exclusion zones declared by the British around the Malvinas, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands. Within these zones, there were very few restrictions. Structuring and altering directives for action were tightly and centrally controlled from Whitehall. Changes normally required coordination between land, sea, and air forces and ministerial approval. However, expedited procedures were in place for urgent changes, such as the one that allowed the attack on the ARA Belgrano outside the exclusion zone.

The War at Sea

The Malvinas conflict included the first true naval confrontation since the Pacific campaign of World War II. The toll on the Royal Navy inflicted by the Argentine Air Force and Naval Aviation during the war at sea included the British destroyers HMS Sheffield and Coventry, the frigates HMS Ardent and Antelope, the landing ship HMS Sir Galahad, and the merchant ship Atlantic Conveyor. Additionally, two British destroyers, fourteen frigates, and two landing ships were damaged during the conflict, primarily by Argentine air attacks using bombs, missiles, rockets, and cannons, except for the destroyer Glamorgan, which was hit by an Exocet missile launched from land. Thirty-seven British aircraft were lost due to various causes.

The fourteen unexploded bombs embedded in British ships' hulls could have easily doubled the losses if their fuzes had been properly calibrated. The British Task Force deployed virtually all existing submarine weapons against false submarine contacts. The Task Force lacked in-depth defense. They did not have the kind of support that the deck of a large aircraft carrier could provide with embarked tactical reconnaissance and early warning aircraft. They were forced to rely on small, inexpensive combat ships whose inferior armament made them more vulnerable than large, well-armored ships, whose only disadvantage was their high cost.

We tend to think of the Malvinas naval campaign only in terms of unit losses and the impact these had on the final outcome. However, for a nation closely observing the facts, there is an additional discussion. The Malvinas naval war also included:

- The first use of modern cruise missiles against ships of a first-rate navy.

- The first sustained aerial attacks against a naval force since World War II.

- The first combat use of nuclear-powered submarines.

- The first known combat use of vertical/short takeoff and landing aircraft.

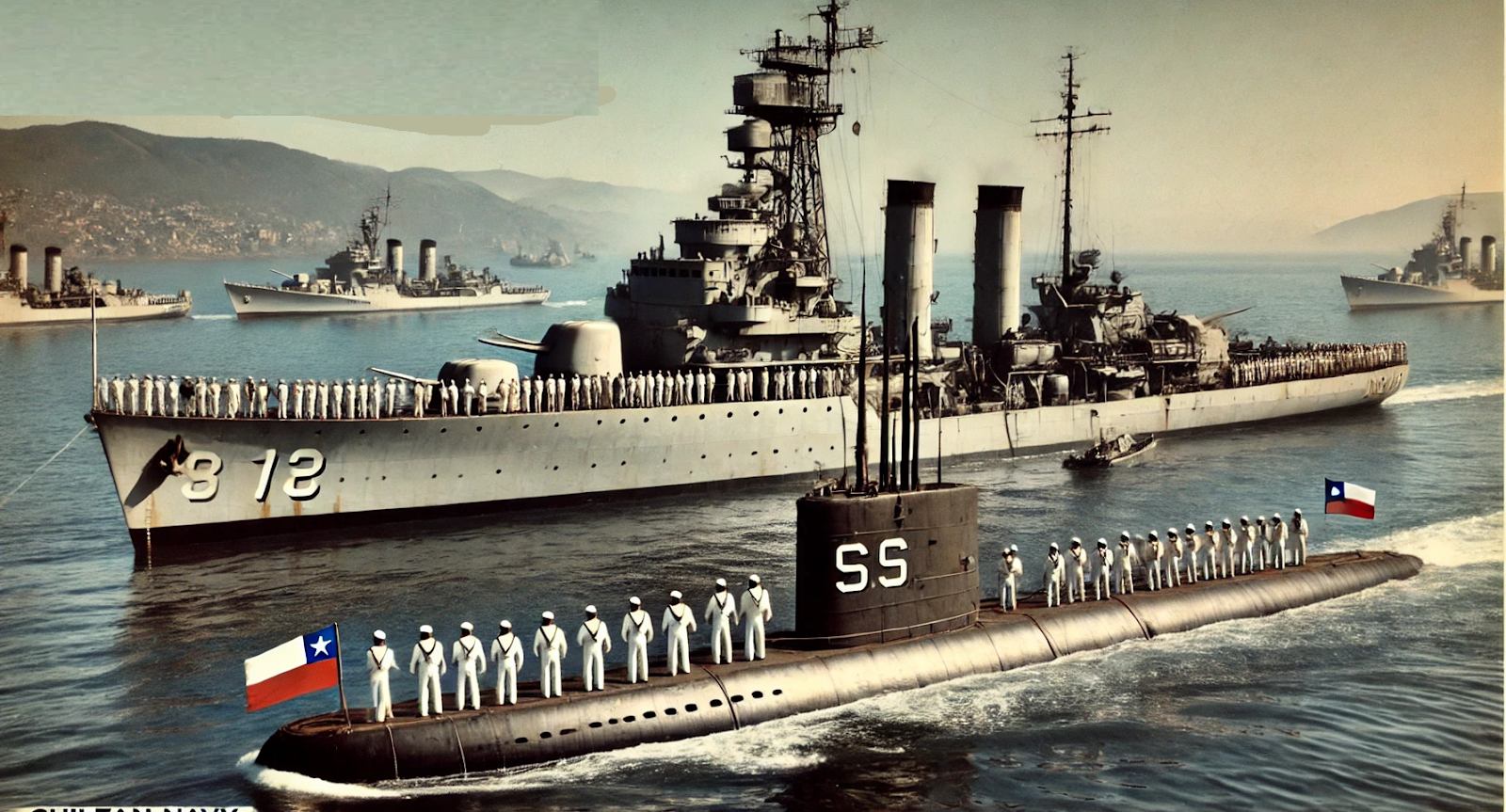

- A small force of Argentine diesel-electric submarines caused enormous concern to British naval authorities and influenced naval operations as much as the air threat, prompting the use of significant amounts of anti-submarine weaponry.

- A similarly small force of British attack nuclear submarines shaped Argentine naval commanders’ decisions and kept Argentine surface units in protected waters. It also influenced some of the first political decisions made at the onset of hostilities.

Selection of the Landing Site

From the departure of the fleet toward the Malvinas, one of the primary decisions faced by planners was determining the location for the initial assault. British thinking on the site and timing of the campaign’s first landing was guided by many considerations. Some of the most important were:

- Political convenience: The British government’s perception of the need to engage with Argentine forces to appease British public opinion eager for action.

- Proximity of the southern hemisphere winter, with its accompanying environmental challenges.

- Effects on morale, training, and the general physical condition of ground forces subjected to prolonged stays ashore in harsh climatic conditions.

- Logistical challenges of maintaining a large ground force in operations for an extended period.

- Transport difficulties in moving a large ground force and its support across the rugged terrain of the Malvinas.

- Lack of intelligence on the morale and training of Argentine soldiers in the Malvinas.

- Lastly, British staff had to choose between two diametrically opposed concepts for the initial assault on the Malvinas: conducting a mass landing through an audacious operation at or near Port Stanley, close enough to immediately target the campaign’s main objective, or conducting a more administrative landing at an undefended site far enough from Port Stanley to make it difficult for Argentine ground forces, mostly concentrated in Port Stanley, to attack the fragile beachhead.

The sites considered by the British as potentially suitable for the initial assault were:

- Stevely Bay, Soledad Island: The farthest from the objective and the least vulnerable to potential Argentine counterattacks by ground forces. At one point, the possibility of constructing an airstrip there to replace the aircraft carriers was analyzed.

- San Carlos, Soledad Island: Closer to the objective and still in a location that made an Argentine counterattack difficult.

- Bluff Cove, Soledad Island: Even closer, but also more vulnerable to an Argentine counterattack.

- Berkeley Sound, Soledad Island: Closer still to Port Stanley, but so close that an Argentine ground counterattack was almost certain.

- Puerto Argentino, Soledad Island: Rejected almost immediately due to the inherent risks.

Initially, it was agreed to conduct the landing at a site where no initial resistance was expected. The plan under Brigadier General Julian Thompson consisted of consolidating the beachhead while awaiting reinforcements arriving from the UK. Once these reinforcements arrived, the command of all land operations would be assumed by Major General Jeremy Moore.

The pros and cons analyzed by planners when selecting San Carlos as the initial landing site included:

- The protection offered by the restricted waters of the anchorage against submarines.

- The natural protection provided by the surrounding high ground for landing ships against air attacks, and its excellent potential for positioning Rapier missile anti-aircraft batteries.

- Intelligence reports indicating the absence of enemy presence in the area, except for infrequent patrols.

- Reports from the Special Boat Squadron (SBS) confirming the absence of mines on the beaches and no evidence of mining activity in the adjacent sea.

- The anticipated delay in an Argentine response due to the distance—approximately fifty miles of rugged terrain—from Port Stanley.

- The distance and rugged terrain between the landing site and the main objective, Port Stanley, which ground forces would have to cross in some manner.

- The proximity of a strong Argentine garrison at Goose Green, thirteen miles south of the site.

- The lack of suitable beaches for landing large numbers of troops and equipment.

- The proximity of high ground in the surrounding area that could be used advantageously by the enemy to repel and dislodge the landing forces.

- Although not verified by SBS patrols, the possibility that the Argentines had mined or intended to mine the maritime approaches to the site, given its obvious suitability for a landing. (At least in the minds of British planners, this was obvious. We now know that Argentine planners, in a pre-conflict study, deemed the site unsuitable for a successful amphibious landing.)

General Argentine Land Strategy

The Argentine land strategy was explained after the conflict by the commander in charge of the Malvinas, stating:

- The first and main military objective was Puerto Argentino. It was the campaign’s linchpin, as it was the seat of political power, home to the majority of the population, and housed the main port and airfield.

- The initial operational concept was to defend Port Stanley from direct attacks using the airfield and aircraft.

- The second phase involved building defenses to repel a direct amphibious assault. Three battalions were deployed to counter attacks from the south and another three to defend the north and west.

- Regarding attacks from the west, the defensive perimeter was determined not only by the terrain but also by the difficulty of maintaining distant troop positions due to limited mobility resources.

- There were high points dominating the inner part of the perimeter that had to be occupied and defended, but there were even better high points further out. However, the ground force commanders judged that they lacked the necessary mobility to occupy and maintain those more distant positions with the personnel and means available.

- This plan probably discouraged the British from attempting a heliborne assault on Port Stanley and may have similarly deterred plans for a direct amphibious assault. This allowed Argentine ground forces to reinforce and adjust their defenses while the British sought another landing site.

The time gained by this arrangement of forces in Port Stanley was not utilized effectively because political leaders in Buenos Aires failed to achieve a political solution to avoid the war. Ground force commanders believed this arrangement gave the political leadership an additional fifteen days to find a diplomatic solution. However, the negative aspect was that the Junta, despite the events involving the ARA Belgrano and HMS Sheffield, continued to focus primarily on a negotiated resolution rather than advancing a military strategy. Military commanders viewed the sinking of the ARA Belgrano and HMS Sheffield as the point of no return for the war, while political leaders saw the "exchange of blood" as an opportunity to reopen negotiations.

The Army believed that this mindset of the Junta restricted action and deprived ground forces of their main weapons, particularly air power. British naval forces surrounded the islands and waged a war of attrition against Argentine ground forces while preparing for their landing. They landed with their landing forces intact. Army commanders believed this occurred because political authorities in Buenos Aires restrained the Air Force and Navy from acting to their full capacity. The Army believed that if the Navy and Air Force had persisted in their attacks on naval transports and aircraft carriers by May 30, the outcome could have been different. However, the attack came far too late. The beachhead had been established, and British troops were advancing freely.

When the British landed, the Army began to consider modifying its defensive positions, reinforcing those protecting Port Stanley from attacks from the west. This realignment of forces began five days late. Western positions were reinforced with weapons, but moving them further west was impossible due to mobility and distance limitations. Efforts were made to cover the distance between Port Stanley and San Carlos with commando patrols, but by the time this decision was made, the British had already occupied the outer high positions. The commandos fought efficiently on several occasions but could not significantly slow the pace of the advance.

The Argentine Sector

The Argentine invasion plan had been entirely conceived as a short and peaceful occupation of the Malvinas by a relatively small force, not as sustained operations by a large force preparing for and ultimately engaging in combat. Operation Rosario was planned and initially executed as a "diplomatic invasion," intended as a nudge to the stalled negotiations with the British over the sovereignty of the islands. The operation was never intended as a combat operation.

The British reaction to the invasion, which consisted of the rapid assembly and deployment of a large naval task force, including amphibious assault units, was initially unforeseen by the Argentines. Argentina’s response to the realization that combat with the British in the Malvinas would be inevitable was a large-scale reinforcement of the islands—an alternative not foreseen in the original plan. This created a logistical nightmare for the Argentine supply system, which likely would have struggled to sustain even the far more limited original operation.

The logistical situation worsened further due to the Military Committee's decision not to use ships for reinforcement or resupply after April 10, following the British declaration of a maritime exclusion zone starting April 12. This decision forced Argentina to rely entirely on air transport and, where possible, fishing vessels.

Border with Chile

Even with the logistical challenges mentioned above, the Argentine force assembled and tasked with the defense of the Malvinas could have been composed of better-trained and equipped troops had Argentina not retained many of its most effective troops on the mainland. This decision was explained as militarily prudent, preserving these forces in reserve against a potential attack by Chile.

The Argentine force assembled under the original plan and used in the initial phase of the conflict was sufficient for a short-term "diplomatic invasion." With no immediate British military threat present in the theater, the basic Argentine concept appeared to be putting enough uniformed bodies on the islands to demonstrate that the territory was under Argentine control, thereby forcing the stalled diplomatic process to resume. Unfortunately for Argentina, when the British threat materialized, their thinking did not adapt, and their efforts to reinforce the islands were simply extensions of the original concept: for example, sending more personnel to reinforce the illusion of control and push for a diplomatic resolution to the situation.

Argentines later admitted that at no point during the planning of the Malvinas retaken did they believe they could win if the British decided to fight for the islands. Unfortunately, this preconception prevailed throughout the conflict, influencing decisions and weakening Argentina’s overall military capability.

Static Defense

The basic Argentine concept for the defense of the Malvinas appears to reflect this preconception. The plan did not foresee an aggressive ground campaign to fight and repel British invasion forces, regardless of where they landed. Instead, Argentina’s defense of the Malvinas relied on a series of static strongpoints around Port Stanley, which were expected to appear so formidable that the British would be deterred from invading. If they did invade, they would supposedly avoid landing near Port Stanley, and if the British landed elsewhere, it was assumed they would opt for a diplomatic resolution before attempting to attack the town.

Following this defensive concept, the Argentines concentrated nearly all their ground forces around Port Stanley throughout the conflict and simply waited for the British attack to arrive. There was never any serious attempt by Argentina to leave their entrenched positions and seize the initiative in the ground war against the enemy.

The Ground War – The British Perspective

The British also faced challenges and made some difficult decisions before the actual Malvinas invasion at San Carlos.

Although the deterioration of the South Atlantic situation had been closely monitored by the British, the Argentine invasion of the Malvinas came as a genuine surprise. There is no doubt, however, that the British demonstrated great ingenuity and determination by assembling a task force of thirty-six ships and setting sail for the Malvinas just two days after the invasion. However, due to the hasty departure, the ships of the landing force were not tactically loaded in the UK, meaning that the equipment and supplies could not be unloaded in the order required by the landing force once they were ashore. This situation was partially rectified during the delay at Ascension Island, where additional equipment was loaded, and an inventory of existing stores was conducted. This period was also used to reorganize cargo holds to facilitate unloading in the combat area. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the unloading of the ships delayed the supply of equipment to the San Carlos landing area.

The Landing at San Carlos

Despite all the doubts about the choice of landing site and concerns over the multitude of things that could go wrong, the British landing at San Carlos was completely uneventful in terms of troop transport ashore. The British amphibious task force approached and arrived at the target area undetected, aided by the cover of darkness, poor weather conditions, and diversionary operations conducted at Goose Green, Fanning Head, and other locations on East Falkland.

British troops landed in the early hours of May 21, encountered no resistance from Argentine ground forces, and moved quickly to their planned defensive positions around the area. As time passed, the anticipated Argentine threat to the landing failed to materialize. The military battle fought at San Carlos became one between the Argentine Air Force and Naval Aviation and the ships of the British amphibious task force.

To their frustration, British ground forces found themselves relegated to the role of spectators in these actions while waiting for orders to advance. Meanwhile, the primary challenges faced by the ground assault forces were the environment, poor logistical support, and boredom.

Although not directly involved in the air-sea battle taking place at San Carlos, the ground forces were nonetheless affected by the outcome of this action.

On the first day of the assault on San Carlos, the British lost a frigate and sustained damage to four others due to Argentine air attacks. In the days following the landing, British naval losses continued at an alarming rate. Confronted with the Argentine air threat, the British were forced to alter their Basic Logistical Plan for supporting the ground forces, shifting from a concept based on afloat depots to one focused on the massive offloading of equipment onto land.

This change in plans was tied to the necessity of restricting ship movements to nighttime and a significant miscalculation regarding the number of helicopters needed to transport equipment, resulting in painfully slow logistical growth on land. A near-fatal setback for the progress of the ground campaign occurred on May 25 with the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor, which had been carrying three Chinook helicopters whose high load capacity was vital for the timely execution of logistical and operational plans. This loss placed an even heavier burden on the remaining helicopters, which were subsequently almost entirely dedicated to equipment transport for the remainder of the conflict.

British Maneuver Plan

Notably absent in the planning for the San Carlos landing was consideration or discussion of what the ground force should do once ashore.

The operation was a landing plan, not a ground campaign. As someone humorously remarked, it was assumed that, once on land, the forces would simply advance and win.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the British, either consciously or unconsciously, expected the Argentines to quickly react and oppose the landing with ground forces. In this scenario, the use of British ground forces would, to some extent, be guided—at least in the short term—by the actions and defensive reactions required during this confrontation.

When the anticipated Argentine opposition to the landing failed to materialize, the British found themselves somewhat at a loss regarding what to do with their ground forces.

Boletin del Centro Naval 748 (1987)