The Malvinas/Falklands Betweeen History and Law

Refutation to the British Pamphlet “Getting It Right: The Real History of the Malvinas/Falklands”

by Marcelo G. Kohen and Facundo D. Rodríguez

Introduction

In 2008, Graham Pascoe and Peter Pepper, two British authors who are not academics, published both in English and in Spanish a pamphlet entitled “Getting it Right: the Real History of the Falklands/Malvinas”. Since then, a variety of versions of this pamphlet have been published, some abridged, and some not; the most recent version, officially distributed by the British government in the United Nations Decolonization Committee in June 2015, was pompously entitled: “False Falklands History at the United Nations. How Argentina misled the UN in 1964 – and still does”. These pamphlets are widely disseminated on British websites devoted to the Falklands/Malvinas issue. The arguments raised in these texts have been taken up by official British notes in the United Nations, as well as by British petitioners before the UN Decolonisation Committee. In general, it is the first time in the history of this longstanding conflict that these arguments and alleged “facts” have been advanced, and they flagrantly contradict the positions adopted by the colonial power throughout the long decades this dispute has lasted. This simply constitutes an attempt to rewrite history. That is why we believe it is important to rectify the mistakes, misrepresentations and fallacies contained in what has already become an officious British document.

The British pamphlet has a double intention: to attack the solid historical-legal arguments which prove Argentine sovereignty, and to convince the reader that the islands are inhabited by a multinational population entitled to the right of self-determination. Paradoxically, in the attempt to undermine the Argentine thesis, “Getting it right...” recognises a series of facts that official British propaganda has attempted to conceal for decades. Traditionally, for the United Kingdom, the key dates in this dispute were: 1592, the year in which John Davis, a British sailor, allegedly discovered the islands; 1690, when Captain Strong, another sailor, supposedly set foot on the islands for the first time; 1766, year of the British settlement at Port Egmont; and 1833, year of the British occupation (and the consequent eviction of Argentina). In trying to refute Argentina’s arguments, the authors of the British pamphlet point out that there were “Portuguese” sailors who discovered the islands and that in the 1540 a Spanish ship moored at the islands for several months – many years before the purported British “discovery”. They also admit that the islands were effectively occupied by Spain until 1811, that David Jewett, a representative of the government of Buenos Aires, took control of the islands in 1820, and that the current settlement in the islands was founded by Luis Vernet. Obviously, these admissions are accompanied by a series of inaccuracies and distortions, which the present work shall examine.

In the attempt to justify the new image portrayed by the British government of a “multinational” population in the Falklands/Malvinas , the authors of “Getting it right...” acknowledge that in 1833, at the moment the British occupied Port Luis or Soledad, the population of the Falklands/Malvinas was Argentine, and ruled by Argentine authorities. In reality, never in history had there been the slightest trace of a British presence in Soledad/East Falkland island. The pamphlet’s authors focus their efforts on explaining that only the military garrison was expelled, and not the Argentine inhabitants. This spurious argument will be also examined in detail. Pascoe and Pepper’s pamphlet also brings to light another point. In attempting to refute the Argentine thesis, they highlight its consistency: Argentina’s position has remained exactly the same since the time of independence. On the contrary, the pamphlet shows up all the contradictions of the British thesis and follows a simplistic reasoning that as the islands “are not Argentine”, then they should be British. It is more than sufficient to compare the arguments Argentina invoked at the time David Jewett took possession of the islands in 1820 and in the 1829 Decree for the creation of the Political and Military Command of the Malvinas Islands and Adjacencies with the arguments it raises at present to prove that they have been consistent throughout: the arguments are simple and always the same. It is instead undeniable that, comparing the arguments submitted by the British government when it first notified Argentina of its claim to sovereignty with the positions it currently maintains, these have changed significantly over time – a telling sign of their legal weakness. Let us briefly recall both positions.

Argentina’s position is clear. The islands are Argentine by virtue of its succession to Spain’s rights, the concrete display of sovereignty by the new South American nation from the beginning of the process of independence in 1810 until 1833, year of the eviction by Britain, and the lack of Argentine consent to the British occupation since 1833. The succession to Spain’s rights is justified by the recognition of Spanish sovereignty by the main European maritime powers, by Spain’s continuation of France’s right of first occupant (1764), and by its continuous exercise of sovereignty over the islands until 1811 – an exclusive exercise between 1774 and 1811.

On the contrary, the British position has been defective and made in bad faith from the outset. In its protest of November 19th, 1829 against the creation of the Political and Military Command of the Malvinas/Falkland Islands by the government of Buenos Aires, the British government based its claim of sovereignty on discovery, the subsequent occupation of the islands, the restoration of the British settlement at Port Egmont by Spain in 1771 and on the fact that the withdrawal of that settlement in 1774 did not amount to a waiver of its purported rights. In order to justify such a position, the British note dated November 19th, 1829 points out that British insignia were left behind on the islands together with the intention of resuming the occupation in the future. Pascoe and Pepper’s pamphlet itself confutes the thesis of British discovery, which, what is more, could not alone constitute a title to sovereignty. The subsequent occupation was not one, as when the British settled at Port Egmont, France had already been occupying the islands for two years. The British government’s note of 19 November 1829 hid not only the fact that the return by Spain of Port Egmont in 1771 was effected preserving Spanish sovereignty, but also the lack of any objection to Spain’s uninterrupted and exclusive presence on the islands ever since Britain abandoned Port Egmont. It also does not take into account Spain’s destruction of buildings and its removal of British insignia from Port Egmont, to which there was no reaction from London.

It is no wonder that in the face of the extreme weakness of the British claim, Pascoe and Pepper’s pamphlet seeks out new arguments. The most original of these is Argentina’s supposed waiver of its claim by entering into the Southern-Arana Treaty in 1849, thanks to which the British blockade of the Río de la Plata, which affected both Argentina and Uruguay, came to an end. The present work will provide a detailed refutation of this argument. Suffice it to note that from 1850 to 2013, the United Kingdom never invoked such a waiver – despite an abundance of opportunities to do so. Not a word was spoken by the British government in any bilateral diplomatic exchange or in any international setting in which the parties have set out their opposing positions on the question of sovereignty. Not a single internal comment exists by colonial officials or by the Foreign Office bringing attention to this alleged waiver of a claim to sovereignty. For example, the British Embassy’s note to the Argentine Minister of Foreign Affairs issued on January 3rd, 1947 explains the British point of view in the following manner:

The Falkland islands have been sustainably under the effective British administration for more than a century. It is true that during that period, from time to time, the Argentine government claimed its sovereignty of the islands and made reservations in that respect. Likewise, during such period, Her Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom in each occasion stated that there had no doubt about Her Majesty’s sovereignty rights of these islands. 2

This was Britain’s position until 2013: it had never before invoked the existence of a treaty through which Argentina gave up its right to sovereignty, something any State would invoke in the face of a claim going against something stipulated in an agreement. It is also naive to claim that Vernet’s settlement of the 1820s was authorised by Britain. This vain attempt to distort history contributes to highlighting an undisputable truth: the first successful effort to bring civilisation to the islands and to inhabit them was made by Argentina. Previous European presence on the islands had an essentially military objective.3 This work will readily show how unfounded this new British argument is – an argument never previously raised throughout the over 180 years this dispute has lasted.

This site is composed of six sections which follow, as far as possible, the order of the arguments developed in the British pamphlet “Getting it right...” The responsibility for the contents of this site falls entirely and exclusively to the authors, who received no direction, grant or remuneration whatsoever.

Chapter I

Papal bulls and discovery. British recognition of Spanish sovereignty

This first section tackles Pascoe and Pepper’s analysis of papal bulls, the Tordesillas Treaty and the discovery of the Falklands/Malvinas Islands.4 These are in reality only secondary issues, because the essence of the Spanish, and consequently Argentine, claim is based on other arguments, such as: 1) recognition by maritime powers – including England – that the region, including the islands, belonged to Spain; 2) the right of first occupancy and 3) the continuous, public and peaceful exercise of sovereignty until 1811.

A. Papal Bulls and the Tordesillas Treaty

The grant of pontifical letters, known as papal bulls, was a standard procedure in the European Late Middle Ages in accordance with the public law of the time. On a variety of grounds, Popes had granted titles of sovereignty with some frequency, from the donation of all the islands in the known world made by the Roman Emperor Constantine to the obligation of Christian sovereigns to spread the faith throughout the world.

Pascoe and Pepper maintain that the Bull Inter Caetera issued by Pope Alexander VI in 1493 (they do not mention the Bull Dudum si Quidem nor the Bull Ea Quae issued by Pope Julius II) is in violation of the principle of classic Roman law “nemo dat quod non habet” (“nobody can give what they do not have”). On the basis of this assertion, they affirm that the Pope did not have the authority to grant something that did not belong to him. 5

Nevertheless, this was the practice followed by all Christian sovereigns before the schism: in 1155, England benefitted from the Bull issued by Adrian IV, which granted Henry II the dominion of Ireland. It is also worth recalling the grant of Corsica and Sardinia to James II 13 in 1297 and the Bulls granted to the kings of Portugal in the second half of the XV century, which secured their conquests in Africa.

The British pamphlet asserts that papal bulls were not accepted by the kings of England and France. However, they fail to point out that, at the moment of their issuance, the kings of those countries were Catholic and recognised the Pope’s authority over Christian princes, making the bulls opposable to the kings of Spain and Portugal as well as France and England. Papal intervention in international conflicts and the distribution of territories had become a custom of European public law, and was generally accepted and recognised by those who viewed the Pope as the highest authority in the Christian world.

England’s responses to Spanish and Portuguese claims were based on the geographical application of the Bull Inter Caetera, and not on its legitimacy. In London’s opinion, the Bull did not include North America. This becomes apparent from the Letters Patent granted by Henry VII to Gaboto and the legal justification of the discoveries made in the northern portion of the New Continent.6 It took almost a century for Queen Elizabeth of England to contest the papal Bull as a “donation”, despite recognising Spain’s sovereignty over the regions in which it had established settlements or made discoveries.

The authors of the British pamphlet criticise the Tordesillas Treaty of 1494 between Spain and Portugal for its disregard of the rights of the Incas, Aztecs, Mayas and other peoples existing at the time.7 This question clearly has nothing to do with that of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands. The use of this argument to justify a purported British right to the New World is intriguing, considering that Great Britain has proven to be the foremost colonial power of all time, subjugating entire populations in all four corners of the world. The issue of the Falklands/Malvinas itself is evidence of Britain’s contempt for the rights of a newly independent nation in South America.

The Tordesillas Treaty was a bilateral agreement which England did not object to at the time of its entry into force, and was endorsed by the Bull Ea Quae issued by Pope Julius II in 1506. Its object was to settle disputes which existed between the contracting parties. Therefore, the fact that the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands are located to the east of the line established by the Tordesillas Treaty is irrelevant in a dispute between Argentina and the United Kingdom.

The British pamphlet unsuccessfully attempts to undermine the importance of Britain’s recognition of Spanish sovereignty over the southern regions of the American continent.

Spain considered those lands and seas to rest exclusively under its competence, and only authorised other nations to settle or navigate the regions by agreement in conventions. The network of treaties entered into by Spain and England through which the latter recognised the exclusive rights of the Spanish Crown over this portion of the globe, including the Treaty of Madrid (1670), the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), and the Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial or Nootka Sound (1790), will be examined below.

B. Pascoe and Pepper acknowledge that England did not discover the Falklands/Malvinas

It is well known that States, and the majority of jurists, in the 18th and 19th centuries did not consider mere discovery sufficient to constitute a title of sovereignty. Nevertheless, the British government made its alleged discovery of the islands into one of its main arguments. This argument was made in protest at Argentina’s exercise of sovereignty, and has continued to be raised until the present day. However, discovery only meant an inchoate title, which had to be perfected by effective occupation as long as the region in question was not under the authority of another power.8 This argument cannot be invoked by the United Kingdom with respect to the Falklands/Malvinas Pascoe and Pepper recognise that the Falklands/Malvinas were not discovered by English sailors. Like another pamphlet published by the so-called (British) Government of the islands,9 they merely maintain that the alleged sighting of the islands by John Davis in 1592 was the first to be published. However, they recognise that many decades before, Iberian sailors sighted the islands, with Spanish sailors spending months in the Falklands/Malvinas, and that the islands already appeared on a variety of maps.10

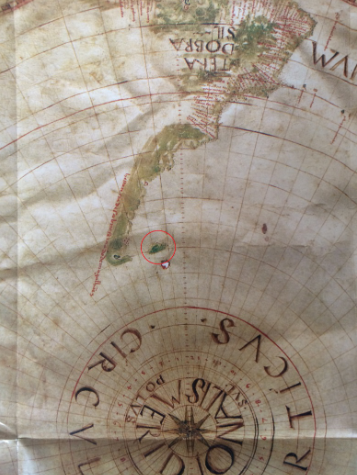

Figure 1 Pedro Reinel's map of the year 1522 where the Islands are observed.

The pamphlet issued by the British “Government” of the islands goes even further and continues to maintain that Richard Hawkins was the first to claim the islands for the British Crown. It is worth remembering that Hawkins’ supposed discovery/claim was not published until 1622 (28 years after the alleged event). Let us examine the fantastic “description” Hawkins himself made of his route:

The wind continued good with us, till we came to forty-nine degrees and thirty minutes, where it tooke [took] us westerly. (...) The second of February, about nine of the clocke [clock] in the morning, we discoveryed [discovered] land, which bare south-west of us, which wee [we] looked not for so timely; and coming nearer and nearer unto it, by the lying, we could not conjecture what land it should be; for we were next of anything in forty-eight degrees. (...) The land is a goodly champion country, and peopled. We saw many fires, but could not come to speake [speak] with the people. It hath [has] great rivers of fresh waters. It is not mountainous, but much of the disposition of England, and as temperate. 11

It is simply impossible for this description to correspond to the Falklands/Malvinas, which are located to the east of the continent: Hawkins was heading south-west of San Julián, that is to say, towards the continent. He was at latitude 48° south, and the Falklands/Malvinas are located at 52° south. Finally, the bonfires rule out any remaining possibility. The islands were uninhabited. What Hawkins saw (if he saw anything at all) were not the Falklands/Malvinas.

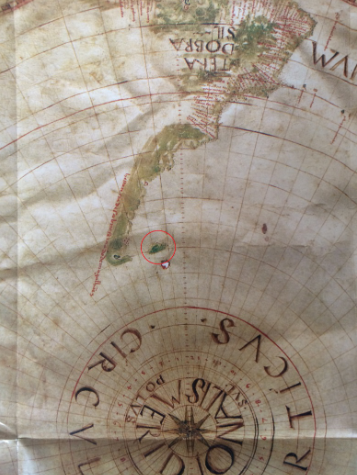

Figure 2 First specific map of the Islands ever made. By Captain Pilot Andrés de San Martín in 1520.

The islands have been included on maps and pilot books since 1502 (among others, the pilot books of Kunstmann II, in 1502; that of Maiollo, in 1504; those of Nicolaus of Caverio, in 1505, Piri Reis in 1513 and Lopo Homen in 1519, and on the map of Pedro Reinel, 152212). It has been established that the first specific map of the islands was made in 1520. This emerges from the French manuscript (1586) Le Grand Insulaire et pilotage d’André Thevet Angoumoisin, cosmographe du Roy, dans lequel sont contenus plusieurs plants d’isles habitées et deshabitées et description d’icelles”, kept at the National Library of France and now available on the Internet.13 This map was drawn by the Captain and Pilot Andrés de San Martín, a member of Magellan’s crew, who seems to have travelled to Spain on the ship “San Antonio” (under the command of the pilot Alvaro de Mesquita) as part of Magellan’s expedition. This was the first crew to set foot on the Falklands/Malvinas, as proven by the records of Alonso de Santa Cruz published in his work El Yslario general de 18 todas las yslas del mundo, enderecao a la S.C.C. Magestad del Emperador y Rey nuestro Señor, por Alonso de Santa Cruz, su cosmógrafo mayor, where the author describes in detail the stopover of Magellan’s ships at Puerto San Julián, and the survey of what at present we know as the Falklands/Malvinas, which he calls “Ysla de Sansón y de Patos”, and named “Isles de Sanson ou des Geantz” by Thevet.14

One reference on the subject, which the authors of the British pamphlet clearly reviewed and used but fail to mention, is the aforementioned book by Dr. Vicente G. Arnaud. This author affirms in his detailed work, that the discovery of the Falklands/Malvinas should be attributed to Amerigo Vespucci in his third journey to America (1501-1502), on April 7th, 1502 (the 16th or 17th according to the Gregorian reform of the calendar) as emerges from the “Lettera” to Soderini dated September 7th, 1504, in which after reaching latitude 52° South, Vespucci himself writes:

(...) on the seventh day of April we sighted new land, about 20 leagues of which we skirted; and we found it all barren coast; and we saw in it neither harbour nor inhabitants. I believe this was because the cold was so great that nobody in the fleet could withstand or endure it.15

Vespucci then elaborates further in Quatour Navigationes: “It lasted for five days so terrible storm, where we had to navigate entirely a bare poles, entering into the sea two hundred and fifty leagues”.16 As De Gandía illustrates, if you take a map, look at the parallel of 52° South and then move two hundred and fifty leagues away from the coast, you will undoubtedly find the Falkland/Malvinas islands.17 El Grand Insulaire by André Thevet, the cosmographer of the King of France, also leaves no room for doubt regarding the discovery made by Magellan’s expedition.

Pascoe and Pepper also admit that a Spanish ship landed in the Falklands/Malvinas and spent several months on the islands in 1540.18 The vessel was named “Incognita” by Julius Goebel – a renowned American scholar, author of the first in-depth research on the dispute over sovereignty of the Falkland/Malvinas islands – since the vessel’s name had not been recorded.19 It is surprising that Pascoe and Pepper do not give importance to this fact, instead highlighting the “non-discovery” made by John Davis. The expedition of the “Incognita” was sponsored by the Bishop of Placencia and commanded by Alonso de Camargo. The Falkland/Malvinas islands were sighted on February 4th, 1540, as proven by the ship’s navigation log, which also reads that said Islands “were on the chart” (meaning that they were not unknown). The “Incognita” wintered until December 3rd 1540, that is to say, it spent almost the whole of 1540 moored on the islands. As maintained by Dr. Arnaud, the vessel relied on the map of the “Isles de Sanson ou des Geantz” made by Magellan’s expedition of 1520, as proven by the detailed description of the number of islands and channels made in the navigation log.20

The British pamphlet maintains that it is not true that the islands were discovered by Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition. The above proves otherwise. What is more, the expedition carried out by the Bishop of Placencia’s Fleet and its effective presence in the islands during 1540 definitively debunks the much-lauded British “discovery” of 1592.

C. “Rival” names of the islands

Pascoe and Pepper’s pamphlet makes a brief excursus on the “rival” names of the islands, aiming to conclude that the British name precedes the present-day Spanish denomination by a century.21 Obviously, this has no legal relevance for the question of sovereignty at all. There are a number of islands in the world originally named by a navigator of one country, but which belong to another. Were this not the case, the Sebaldine Islands (Jason Islands in English), located at the northwestern tip of the Falkland/Malvinas archipelago, Staten Island, or Cape Horn on the Tierra del Fuego archipelago should all be Dutch, as they were named by Dutch sailors.

The real problem here is that, in stating that the Spanish never named the islands, the British authors are distorting history. We saw that the first map made of the islands was Spanish, in which they are referred to as “Sansón o de los Patos”. Later, the Spanish named them “Islas de los Leones”, as the Spanish minister Mr. José de Carbajal pointed out in his response to Benjamin Keene when the British attempted to send an expedition to the Falkland/Malvinas islands.22 It is true that the Spanish name which finally prevailed was a name of French origin, at the very time in which European powers were beginning to settle in the islands. We will see below that France was the first effective occupant of the islands and that its settlement was continued by Spain. Paradoxically, Pascoe and Pepper neglect to mention that the English terminology also changed over time, and at one point the islands were called “Hawking Maidenland”23

The fact that the name of the same territory or geographic feature may vary in different languages is nothing new. The English, French and Spanish names of the islands have their own heritage and must be equally respected in all three languages. This used to be standard practice. Unfortunately, the persistent dispute over sovereignty has given a political connotation to the use of these names, a meaning that they clearly do not have. This is a minor issue that will be easily solved the day this dispute is finally settled.

D. Bilateral treaties prove that Britain recognised Spanish sovereignty over the region of the Falklands/Malvinas

Pascoe and Pepper analyze the treaties of 1670, 1713 and 1790 superficially and without any discernible method.24 Here, we will review the texts in their context and according to the object and purpose of the treaties, as well as their interpretation and application by the powers concerned, as required by international law. In the treaties, Great Britain makes a variety of undertakings to abstain from sailing to and trading with the Spanish regions of America.

a) The Treaty of Madrid of 1670

The first of these treaties is the Treaty of Madrid, entered into by Spain and Great Britain on July 18th, 1670. According to its preamble, the agreement had the objective to “settle the differences, repress the piracy, and consolidate the peace between Spain and Great Britain in America”. In Article VII, it is agreed that

the Most Serene King of Great Britain, his heirs and successors, shall have, hold and possess forever, with full right of sovereignty, ownership and possession, all the lands, regions, islands, colonies, and dominions, situated in the West Indies or in any part of America, that the said King of Great Britain and his subjects at present hold and possess; so that neither on that account nor on any other pretext may or should anything ever be further urged, or any controversy begun in future. 25

Pascoe and Pepper candidly affirm that, the Treaty thereby recognises Britain’s possessions in North America and the Caribbean, but that there is no similar clause for British recognition of Spanish sovereignty over the rest of the Americas.26 Again, the authors “forget” that in the New Continent, Spanish sovereignty was the rule, and British sovereignty the exception. While Spain questioned the latter, Great Britain did not question Spanish sovereignty. It therefore did not make sense to include a provision in the treaty addressing a point that was uncontroversial. Nevertheless, the subsequent article clears up any doubts in that regard. As we shall see, it concerned the prohibition of navigating to or trading with Spanish territories in America. It is evident that it was impossible to for Britain to acquire sovereignty over areas to which they could not even go.

The British pamphlet considers it “absurd” to claim that there existed a general prohibition

of navigation in regions considered to be Spanish unless by consent of the latter. Nevertheless, Article VIII of the Treaty of 1670 is eloquent in this respect. It establishes that “subjects of the King of Great Britain shall on no account direct their commerce or undertake navigation to the ports or places which the Catholic King holds in the said Indies, nor trade in them.”27

Contrary to Pascoe and Pepper’s interpretation, Article XV does not establish absolute freedom of navigation. The article reads: “The present treaty shall detract nothing from any pre-eminence, right, or dominion of either ally in the American seas, straits, and other waters; but they shall have and retain them in as ample a manner as is their rightful due. Moreover, it is always to be understood that the freedom of navigation ought by no means to be interrupted, provided nothing be committed or done contrary to the genuine meaning of these articles.” In other words, navigation had to respect the provisions of Article VIII; otherwise the article would lose all meaning.

The British pamphlet tries to invoke British possession of Saint Helena as proof that Great Britain was free to navigate in the Southern Atlantic.28 This fact proves nothing; Spain never considered Saint Helena to be in its possession. The island was located in the Portuguese section as established by the Treaty of Tordesillas. The British pamphlet asserts that the treaty “was written with North America and the Caribbean in mind.” As we have seen, this is true with regard to Spanish recognition of British possessions, but the text otherwise clearly refers to “the West Indies” or “America”, terms which leave no doubt regarding the scope of the provisions referring to the navigation and recognition of the sovereignty and pre-eminence of each power in their pespective spheres in America.

The treaty of 1670 was part of a network of treaties between the maritime powers of the time, whose objective was the protection of Spain’s exclusive rights over its dominions and its grant of some licenses to other nations. His Catholic Majesty protected his colonies in America. Great Britain applied the same criterion in the parts of North America under its possession. This was the object and purpose of the treaty, which is also reflected in the legal instruments which will be analysed next.

b) The 1713 Treaties of Madrid and Utrecht

By virtue of the Treaty of Madrid signed on March 27th, 1713, Spain conceded to Great Britain the slave trade within Spanish America. What matters here is navigation. The slave trade implied a derogation of the prohibition on trading with the Spanish colonies and navigating in the adjacent seas. As provided in Article 14 of the treaty: “His British Majesty has certainly agreed upon the promulgation of the strictest prohibitions and has subjected all his subjects to the most rigorous penalties in order to prevent any British vessel from crossing to the South Sea or trading in any other area of the Spanish India, except for the company devoted to the slave trade.”29 The Treaty of Madrid of 1713 confirms our understanding of the Treaty signed in 1670 and refutes the interpretation made by the British authors. There appears an express and unequivocal recognition of the prohibition to navigate the South Seas, except for the British slave trading company.

On July 13th, 1713 Spain and Great Britain signed the Peace Treaty of Utrecht. Its Article VIII confirmed the existing scale of trade and navigation in America, and Spain undertook not to grant American territories to France or any other nation, or to authorise them to sail for trading purposes within Spain’s dominions. Article VIII went on as follows: “On the contrary, that the Spanish dominions in the West Indies may be preserved whole and entire, the Queen of Great Britain engages, that she will endeavor, and give assistance to the Spaniards, that the ancient limits of their dominions in the West Indies be restored, and settled as they flood in the time of the above-said Catholic King Charles the Second, if it shall appear that they have in any manner, or under any pretence, been broken into, and essened in any part.”30 This article does not use the expression “territories possessed” by Spain, contrary to what Pascoe and Pepper assert;31 it guarantees the integrity of all the possessions of the Spanish Crown. It refers to the “ancient limits of their dominions”. The only “limits” were those laid down by the Tordesillas Treaty, with the exception of those already occupied by other nations.32

c) A case of treaty application: Spain’s opposition to the British plan of visiting the Falklands/Malvinas in 1749

A clear example of the application of the treaties in force between the two powers directly concerns the issue of the Falklands/Malvinas: British Admiral Anson’s attempt to conduct an expedition to the Falkland/Malvinas islands in 1749. Significantly, the British government notified the aim of the expedition to the Spanish government, explaining that they had no intention of establishing any kind of settlement on the islands. This attitude illustrates two key points: first, that London did not consider itself to be sovereign over the islands in 1749; and second, that on the contrary, the British recognised Spanish sovereignty over the region.

Admiral Anson submitted a plan to the British government to prepare an expedition to the Falkland/Malvinas islands (and also to the non-existent “Peppys” islands!). The plan was discovered by the Spanish Ambassador in London at the time, Ricardo Wall, who immediately protested. Spain described in detail both the islands and Spanish sovereignty over them, stating that there was no reason for Great Britain to make an expedition to the islands. The Spanish note explained that “if the purpose of the trip was to establish settlements in the islands, that would be construed as a hostile act towards Spain, but if the purpose was to satisfy their curiosity, as much news as they wanted could be provided without the need to incur such expenses merely out of curiosity.”33 The British Ambassador in Madrid, Benjamin Keen, had to explain that the purpose of the trip was merely the discovery of new territories and not to establish any settlement therein. Following the orders given by the Duke of Bedford, who at the time was in the British Secretariat of State for the Southern Department, he stated that: “As establishing a colony in either of the two islands is not the intention and Her Majesty’s corvettes will not go ashore, they will not even get close to the Spanish coast, the King cannot understand that this plan can provoke resentment on Madrid’s part.”34 The Spanish categorically replied in the negative.

Ambassador Keen informed Bedford that the Spanish minister had told him “he adverted to the inutility of pretending to a further examination of them and affirmed they had been long since first discovered and inhabited by the Spaniards; who called them the Islands de Leones from the number of sea lions on their coasts and that in the office books there were ample descriptions of the dimensions, properties, etc. If we did not intend to make any establishment there, what service could this knowledge be to us? We had no possessions in

that part of the world, and consequently could want no passages or places to refresh in.”35

Due to fierce Spanish opposition, Great Britain gave up the project. It is apparent from the exchange of notes that: 1) even though Spain was not physically present on the islands, it claimed sovereignty and opposed any British attempt to reach the islands, 2) Great Britain did not make any claim to sovereignty over the islands, nor did it reject the Spanish claim and 3) Great Britain accepted to not send an expedition, as requested by Spain.

This case refers the Falklands/Malvinas themselves, no less, and clearly shows the purpose of the treaties entered into by the two powers over their territories in the American continent. The Falkland/Malvinas islands were Spanish, and Great Britain neither objected to this fact, nor claimed sovereignty over them.

d) Pascoe and Pepper recognise that the Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial or Nootka Sound of 1790 was applicable to the Falklands/Malvinas

The British pamphlet makes a considerable, though unsuccessful, effort to undermine a key treaty for the recognition of Spanish sovereignty over the islands and Britain’s obligation to respect it. This is the Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial of 1790, also known as the Nootka Sound Convention, signed by Great Britain and Spain at El Escorial on October 28th, 1790. Notwithstanding their efforts, Pascoe and Pepper have no choice but to recognise that the Treaty in question applied to the Falklands/Malvinas and that consequently Great Britain undertook not to occupy the islands.36

The dispute arose in 1789, when a Spanish naval officer, commissioned by the Viceroy of Mexico, apprehended two British ships at Nootka Sound (near Vancouver Island) and ordered the transfer of their captains and crews to San Blas port, in Mexico. Spain claimed that the British subjects had violated the laws of the Spanish Crown, and Great Britain requested a salute to their flag before discussing the substantive issue. In order to find a solution to this incident and avoid similar incidents in future, the two nations concluded the Treaty of 1790.37

Article IV reads: “His Britannic majesty engages to take the most effectual measure to prevent the navigation and fishery of his subjects, in the Pacific Ocean or in the South-Seas, from being made a pretext for illicit trade with the Spanish settlements; and, with this view, it is moreover expressly stipulated, that British subjects shall no navigate or carry on their fishery, in the said seas, within the space of ten sea-leagues from any part of the coasts already occupied by Spain.”38

The prohibition is crystal clear, as is the fact that at the moment the Treaty was signed, Spain was in sole possession of the Falklands/Malvinas. By that time, Spain had already appointed the 13th Governor of the Malvinas. The prohibition undoubtedly included the Falkland/Malvinas islands, a fact recognised by Pascoe and Pepper. 39

As Julius Goebel asserts, “the terms of the sixth article by inference forbade any landing at the Falklands as they were a place already occupied by Spain.”40 This was the Spanish authorities’ understanding when they took all necessary measures to protect their shores. A concrete example that can apply to the islands is the note dated March 4th, 1794 written by the Governor of the Malvinas, Mr Pedro Sanguineto, addressing the Viceroy Nicolás Arredondo and informing him that he had performed a 41-day navigation to carry out patrol and surveillance activities over the archipelago. In the note, he informs the Viceroy of the presence of vessels of different nationalities (some British), which were cautioned and informed of the prohibition of landing and fishing, save in a situation of “wreckage or shortage of water.”41

Unable of deny the evidence, the British authors attempt to split hairs. In order to do so, they come up with the idea of emphasizing an aspect that not only does not justify the British position, but in fact further bolsters the Spanish/Argentine thesis. It is Article VI, which reads “It is further agreed, with respect to the Eastern and Western coasts of South-America, and to the islands adjacent, that no settlement shall be formed hereafter, by the respective subjects, in such parts of those coasts as are situated to the South of those parts of the same coasts, and of the islands adjacent, which are already occupied by Spain:

provided that the said respective subjects shall retain the liberty of landing on the coasts and islands to situated for the purposes of their fishery, and of erecting thereon huts, and other temporary buildings, serving only for those purposes.” This clearly not only reaffirms the prohibition of navigation and fishing, but also the prohibition of establishing settlements on the coasts and islands already occupied by Spain.

The British authors endeavour to affirm that by virtue of this section of the Treaty of 1790, British subjects were granted the authorization to disembark and build cabins, etc.42

However, this authorization in no way supports the British thesis. It proves three points: 1) that the Falklands/Malvinas were Spanish and that this was recognised by Great Britain; 2) that it was Spain which authorized British subjects to temporarily perform activities of a private nature in its possessions, and that 3) such activities were not in any way connected with the exercise of sovereignty over the Spanish territories.

In this regard, the most eloquent contradiction in the British pamphlet can be found in the analysis of the secret article of the Treaty of 1790. This clause lifted the prohibition on Great Britain to settle south of the coasts and adjacent islands already occupied by Spain, if another nation did so. According to the authors of the pamphlet “Getting it right...”, as Argentina occupied the islands “in the late 1820s”, and the islands had been occupied by Spain since 1790, the secret article would apply and Great Britain would be able to settle in the Malvinas islands as “Argentina had become established there”.43 As we will see below, the same British pamphlet which recognises that Vernet’s settlement was an Argentine public settlement tries to prove otherwise only a few pages later, in an attempt to portray the settlement as a private operation carried out with the prior consent of Great Britain!44

The pamphlet claims that the secret clause was put forward by the British with the Falkland/Malvinas islands in mind.45 In order to prove this, they quote the work of an Argentine author, a collection of three personal letters addressed to the Chilean journalist and diplomat Conrado Ríos Gallardo. This is merely his own speculation. Even if this speculation were proven to be correct, it does not change the clear and concrete impact of the Treaty with respect to the question of sovereignty: Spain was the nation exercising sovereignty over the Falklands/Malvinas in 1790, and Great Britain undertook not to interfere with its possession.

Aside from its blatant contradictions, Pascoe and Pepper´s reasoning is not pertinent. Following their argument, what Great Britain feared in 1790 was a resettlement of the islands by France, or their control by the new-born United States, since most of the fishermen and hunters operating in the area were citizens of the new American nation. In 1790, the Latin American independence movement had not yet been born. When the independence movements did burst onto the scene, they were considered to be part of a civil war within the Spanish Empire. Great Britain was unable to invoke the secret clause, whether in its own favour or against Spain or Argentina, as explained below.

The key point is that the Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial or Nootka Sound of 1790 clearly demonstrates that at the moment the Argentine independence process began in 1810, the Falkland/Malvinas islands belonged to Spain and that Great Britain both recognised this fact and undertook to respect Spanish sovereignty. In spite of the fact that the islands were under Argentine possession in 1833, Great Britain could not possibly ignore the fact that for Spain the islands, as indeed all the territory of the newborn Argentine nation, were still part of its empire of the Indies. There are a variety of reasons why the secret clause could not be invoked against Argentina. Firstly, because Argentina succeeded to Spain’s rights over the Falklands/Malvinas; at the moment in which it recognized Argentine independence and the two nations established diplomatic relations and entered into a treaty of amity in 1825, Great Britain had the obligation to respect Argentina’s territorial integrity. Secondly, even if the secret clause were in force and opposable to Argentina – which is not the case – because Argentina has succeeded to Spain’s rights, there was no settlement established by “subjects of other powers”, but only a continuation of Spain’s rights.

British sources concur on the fact that the Treaty of 1790 prevented Great Britain from settling in the Falkland/Malvinas islands. No serious British author, nor the British government itself or its officials considered the secret clause to be applicable after Argentine independence. Professor M. Deas stated in the House of Commons on January 17th, 198346 that “in 1790 the Nootka Sound Convention was signed, by virtue of which,

Great Britain waived the right of establishing future settlements in the east and west coasts of South America and in the adjacent islands; and the Royal Navy indifferently informed subsequent Spanish activities in the islands [Malvinas]. Briefly, we set one foot (but there were others) and we left.”47 The second is a Memorandum issued by the Foreign Office written by John W. Field and dated February 29th, 1928, which reads “On October 28th, 1790 a Covenant was signed between this country and Spain, the section 6 of such covenant provided that in the future, any of the parties should establish any settlement in the east of west coasts of South America and adjacent islands, to the south of such portions of those same coasts and islands at the time occupied by Spain [...]According to this section becomes evident that Great Britain was banned from occupying any portion of the Falkland Islands. This Treaty was abrogated in October, 1795, when Spain declared war to Great Britain. Nevertheless, it was reinforced by section 1 of the additional sections comprised in the Treaty of Amity and Alliance between Great Britain and Spain of July 5th, 1814, signed in Madrid on August 18th, 1814.”48 Even earlier, the Memorandum issued by the Department of History of the Foreign Office dated December 7th, 1910 came to the same conclusion: “By virtue of this section (section 6 of the Treaty of 1790) becomes apparent that Great Britain was banned from occupying any portion of the Malvinas islands”.49

In short, the Nootka Sound Convention is the consolidation of Spanish sovereignty over the entire archipelago. Had the British wished to resettle Port Egmont after 1774, they could have done so by invoking the agreement signed in 1771, which will be the topic of the next chapter. From 1790, they undertook not to do so. Article VI prevented Great Britain from contesting Spanish sovereignty and from occupying any part of the coast of the islands. There are similarities to the Permanent Court of International Justice’s interpretation of the “Ihlen declaration” with respect to Eastern Greenland, except that in 1790 there was no doubt as to the conventional nature of the obligation undertaken by Great Britain “It follows that, as a result of the undertaking involved in the Ihlen declaration of July 22nd, 1919, Norway is under an obligation to refrain from contesting Danish sovereignty over Greenland as a whole, and a fortiori to refrain from occupying a part of Greenland.”50 In 1810, the relevant year for Argentina’s succession to Spain’s rights, the Falkland/Malvinas islands were undoubtedly Spanish. Great Britain was prohibited from occupying and claiming sovereignty over the islands. Argentina’s acts on the islands after independence could in no way affect a British sovereignty that did not exist at all.

2 In Dagnino Pastore, Lorenzo, Territorio actual y división política de

la Nación Argentina, Buenos Aires, UBA, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas,

1948, p. 228 [this is a translation from Spanish].

3 The exception to this was Bougainville’s initial plan, which was, however, unsuccessful: as we shall see, his settlement was transferred to Spain as a consequence of France’s recognition of Spanish sovereignty.

4 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, “Getting it right: the real history of the Falklands/Malvinas”, 2008, pp. 3-6

5 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 4

6 Cf. Mamadou, Hébié, Souveraineté territoriale par traité. Une étude des accords entre puissances coloniales et entités politiques locales, Paris, PUF, 2015, pp. 58-73.

7 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., pp. 3- 4.

8 Arbitral Award in the Island of Palmas case (Netherlands, USA), United Nations, Reports of International Arbitral Awards, Vol. II, pp. 829-971.

9 See section “Our History” and the pamphlet “Our Islands, our Home” on the official website of the “Falkland Islands Government”: http://www.falklands.gov.fk/our-people/our-history/

10 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., pp. 3- 4

11 Groussac, Paul, Les îles Malouines [1892]. Buenos Aires, Ediciones Argentinas SA, 1982, pp. 81-82.

12 Arnaud, Vicente Guillermo, Las islas Malvinas. Descubrimiento, primeros mapas y ocupación. Siglo XVI, Buenos Aires, Academia Nacional de Geografía, 2000, p. 235.

13 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9065835g/f44.image.r=Le%20Grand%20Insulaire%20et%20pilotage

%20d%C2%B4Andr%C3%A9%20Thevet.langFR.

14 Arnaud, Vicente, op. cit., p. 191.

15 Northup, George Tyler, Letter to Piero Soderini, gonfaloniere. The year 1504, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1916, p.39

16 Arnaud, Vicente, op. cit., p. 191.

17 De Gandía, Enrique, “Claudio Alejandro Ptolomeo, Colón y la exploración de la India Americana”, in Investigaciones y Ensayos, Buenos Aires, Academia Nacional de la Historia, 1972, p. 75.

18 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 5.

19 Goebel, Julius (son), The Struggle for the Falkland Islands, Yale, University Press, 1827, p. 33

20 Arnaud, Vicente Guillermo, op. cit., p. 231.

21 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 5.

22 Keene to Bedford, May 21, 1749, cited by Caillet-Bois, Ricardo, Una tierra argentina. Las islas Malvinas. Ensayo en una nueva y desconocida documentación, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Peuser, 2a ed., 1952, pp. 46-47.

23 Groussac, Paul, op. cit.,pp. 82-83.

24 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., pp. 5-6 and 8.

25 Frances Gardiner Davenport, European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies, Washington DC, The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2012, p 194.

26 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 5

27 Frances Gardiner Davenport, op. cit., p 195

28 Ibid.

29 Preliminary treaty of friendship and good will between England and Spain., Del Cantillo, Alejandro (comp.), Tratados, convenios y declaraciones de paz y de comercio que han hecho con las potencias extranjeras los monarcas españoles de la Casa de Borbón desde el año 1700 hasta el día, Madrid, Impr. Alegría y Charlain, 1843, p. 73.

30 George Chalmers, A Collection of Treaties Between Great Britain and Other Powers, Printed for J. Stockdale, 1790, pp. 81-82.

31 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 6.

32 Cf. Zorraquín Becú, Ricardo, Inglaterra prometió abandonar las Malvinas, Buenos Aires, Ed.

Platero,1975, p. 115.

33 Rodríguez Berrutti, Camilo, Malvinas, última frontera del colonialismo, Buenos Aires, Eudeba, 1975, p. 40.

34 Goebel, Julius, op. cit., p. 225

35 Caillet-Bois, Ricardo, op. cit., pp. 46-47.

36 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 8.

37 Ferrer Vieyra, Enrique, Las islas Malvinas y el Derecho Internacional, Buenos Aires, Ediciones Depalma, 1984, p. 67.

38 Comments on the Convention with Spain, London, printed for T. Axtell, 1790, p.12.

39 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 8

40 Goebel, Julius, op. cit., p. 431.

41 AGN Sala IX 16-9-8.

42 Pascoe, Graham and Pepper, Peter, op. cit., p. 8.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Ibid.

46 “Notes on the issue of Falkland Islands sovereignty for House of Commons, Committee on Foreign Affairs”, Great Britain Parliament, House of Commons, Foreign Affairs Committee, sessions 1982-1983, Falkland Islands, Minutes of Evidence, 17/1/83, London, HMSO, 1983 pp. 127-137.

47 This refers to the settlement of Port Egmont. Cf. Ferrer Vieyra, E., Las islas Malvinas..., op. cit., p. 4

48 Memorandum Respecting the Falkland Islands and Dependencies, Confidential (13336), by Field, John.W., February 29, 1928 (FO 37/12735).

49 Memorandum respecting the Falkland Islands, Confidential (9755), by De Bernhardt, Gaston. Printed for the use of the Foreign Office, January 1911, p. 12.