“I am ready”: the Captain’s Courage the Day the Firing Computer of the ARA San Luis Submarine Broke Down in Malvinas

The

recovery of the Malvinas Islands on April 2, 1982 took the commanders

of the submarine force by surprise, as they had not been informed of

Operation Rosario. Nevertheless, they prepared as best they could a

submarine with serious technical deficiencies and sailed with it within

the exclusion zone. The decision of Frigate Captain Fernando María

Azcueta and his inexperienced crew. And the order to destroy the enemy

with the only possibility of firing torpedoes manually.

By Mariano Sciaroni || Infobae

The

drumbeat of war on April 2, 1982 surprised the ARA San Luis (S-32) and

all its crew, including its commander, Frigate Captain Fernando María

Azcueta, 40 years old and son of one of the first submariners of the

Argentine Navy. It was docked at a pier at the Mar del Plata Naval Base

(BNMP), base of operations for the Navy's small submarine force.

ARA San Luis departs from Mar del Plata Naval Base The

surprise was due to the fact that the high naval command, in order to

maintain the secrecy of the operation carried out that day, chose not to

inform the commanders of the various units not directly involved about

Operation Rosario: the capture of the Malvinas.

Therefore, the

San Luis did not receive the order to prepare for a combat patrol until

24 hours after the assault on the islands. At that time, the recently

completed crew began to prepare the ship, in order to make it fit for

war in the shortest possible time.

The initial state of the

submarine was not satisfactory and it greatly needed to enter dry dock,

something that would have to be done at the Puerto Belgrano Naval Base,

the main base of the Navy, since Mar de Plata lacked such facilities.

The

hull, propeller and internal cooling pipes of the San Luis had

accumulations of small parasitic crustaceans, which affected its

performance, increased its noise level and limited its speed. However,

as there was not enough time to travel to Puerto Belgrano, the clean-up

was carried out in Mar del Plata by divers (students from the Diving

School) who worked 24 hours a day, equipped with manual scrapers, for

almost a week.

Frigate

Captain Fernando María Azcueta speaks to his crew during the 1982 war

patrol. The beard indicates that they had already been at sea for quite a

few days

Frigate

Captain Fernando María Azcueta speaks to his crew during the 1982 war

patrol. The beard indicates that they had already been at sea for quite a

few days

Despite intense efforts before departure, several critical issues with the unit remained unresolved. One diesel engine had been out of service since 1976 due to a broken engine block, and the other three suffered from cooling problems that limited their power. Additionally, the snorkel frequently allowed seawater into the submarine, and the bilge pumps were unreliable. The DUUX system, a passive acoustic rangefinder, was deemed inaccurate and out of service.

Survival equipment also posed significant concerns. The life raft ejection system was non-operational, hydrogen burners were outdated, and the oxygen meter was being repaired on land. Gas measurement capsules, crucial for safety, had expired in 1976. This was particularly concerning given that the submarine was considered modern, having been incorporated in 1974.

The crew’s training level was compromised by the Argentine Navy’s personnel rotation policy, which resulted in many new and inexperienced crew members aboard. Key positions, including those in fire control systems, were held by junior non-commissioned officers, as the most experienced submariners were in West Germany overseeing the construction of new TR 1700-class submarines.

Lieutenant Luis Seghezzi, an exceptionally young Chief of Navigation, had just graduated from the Submarine School in late 1981. He reflected on the high turnover among the crew, acknowledging that most had only been on board for three months and that this was his first experience with the submarine's weapon systems. He noted that while high turnover allowed for more personnel to be trained in new technologies, it did not necessarily ensure better responses in unprecedented situations, such as those faced during the mission.

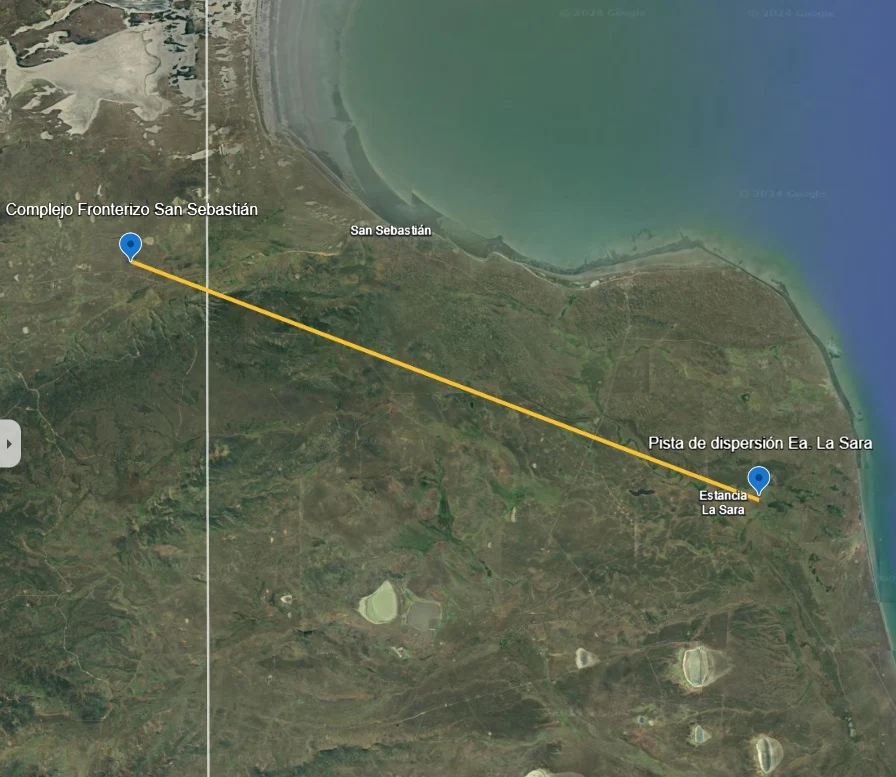

ARA

San Luis's trajectory from the "Enriqueta" area to the exclusion zone,

finally entering the "María" patrol area, within the Exclusion Zone

While the senior officers of the San Luis had extensive experience with submarines, neither Captain Azcueta nor his second-in-command had any with Type 209 submarines like the San Luis. Azcueta himself had only spent 16 days at sea as commander before the war began, having taken command on December 19, 1981.

On April 11, late in the afternoon, the submarine, fully loaded with water, provisions, 10 SST-4 guided torpedoes, and 14 Mk 37 Mod 3 torpedoes, set sail from Mar del Plata with its 35 crew members. Second Corporal Eduardo Lavarello recalls the departure on that Easter Sunday as a cold, foggy evening, which was ideal for remaining undetected as they headed out to sea.

By April 13, Captain Azcueta reported the results of engine tests to his superiors, confirming that the engines operated acceptably up to 1200 amps, achieving a maximum submerged speed of 20 knots. Despite the numerous challenges—limited experience with the Type 209, an inexperienced crew, mechanical issues, and unreliable weapons—Azcueta's message concluded with the resolute words, “I am ready.” This declaration, made in the face of daunting odds and the prospect of confronting the world’s leading navy in anti-submarine warfare, encapsulates the captain’s bravery and determination.

On April 17, 1982, after an uneventful transit during which the captain continued to train his crew and address mechanical issues, the submarine received a coded message. They were ordered to proceed to a waiting area designated as “Enriqueta,” located southeast of Golfo Nuevo, near the Argentine mainland and just north of the British-established Exclusion Zone.

The VM-8/24 computer is out of service

Initially, due to ongoing diplomatic negotiations, there were strict Rules of Engagement that limited the use of weapons, similar to those imposed on British forces. Weapons could only be used within the Maritime Exclusion Zone and after positively identifying a target, except in cases of submerged contacts, which were presumed to be enemy vessels.

Two days later, the VM-8/24 fire control computer on the ARA San Luis failed completely, despite the crew's efforts to repair it. Captain Azcueta later explained that the computer lost its display and the target panels became unresponsive to sensor commands. The crew attempted multiple troubleshooting steps, including checking power supplies and adjusting voltage levels, but the computer remained largely nonfunctional, though it could still operate in a limited emergency mode.

The fire control computer is critical for a modern attack submarine, as it processes sensor data, calculates firing solutions, and controls torpedo guidance. The VM-8/24 system on the San Luis could track and prepare solutions for up to three targets simultaneously, integrating sonar, radar, and periscope data to determine positions and vectors.

The computer’s failure was a severe blow, leaving the submarine unable to use its automatic fire control system. This limitation meant that the San Luis could only fire a single torpedo at a time, which had to be manually guided by the crew, significantly reducing the submarine’s combat effectiveness.

With the breakdown of the computer, according to the post-war report, there was:

- Loss of the ability to automatically and instantly update the positions of the submarine, target and torpedo.

- Loss of the ability to accurately calculate the Aiming Angle (Torpedo Course) and its instant update.

- Poor precision of the manual guidance system dial (graduations every 5° by design)

- Practical impossibility of estimating the position of the torpedo and, as a consequence, serious difficulty in introducing effective corrections.

The seriousness of the breakdown led Azcueta to break the traditional radio silence with which submarines move and inform his superiors. The Commander of the Submarine Force (COFUERSUB) recognized the problem, but decided not to withdraw the ARA San Luis from the waiting area, after assessing the convenience of having at least one submarine patrolling despite the limitations it faced.

According to doctrine, the failure of the computer implies a “low probability of impact” and, therefore, the use of torpedoes is “in case of defensive launches and if no other weapon is available”. Therefore, it was considered that the failure of the computer implied “that the fulfillment of the unit's mission would be practically unfeasible”.

Inside the San Luis, however, and despite knowing the new limitations with which they would go to war, they were somewhat optimistic. As Lieutenant Ricardo Alessandrini, the submarine's Chief of Armament, recalls: “The firing control computer was not operational and left us short of capacity in the waiting area. This limited the number of torpedo shots that could be controlled from the submarine. However, in the submarine force we often practiced the old-fashioned method of firing torpedoes using manual calculations and it was entirely possible to carry out a successful attack with good information about our target.”

That is, the S-32 crew would launch torpedoes using plottings and abacuses, in the same way that straight-running torpedoes were launched at short distances until the beginning of World War II.

Captain Azcueta also narrates: “As has been said, during the stay in the Enriqueta area, we took advantage of the stoppage to intensify the training in the different roles and to adjust ship values that we had not updated. Among them the so-called “cavitation threshold”. In a submarine, the speed at which its propellers cavitate (a fluid phenomenon that produces an undesirable and significant noise of its own), depends on the depth and increases with it. That is, if I increase the immersion plane, I can apply more speed without cavitating. With resignation we verified that, whatever the depth, up to 150 meters, we cavitated at 6 knots. This circumstance led me to be very cautious with the speed in the patrol area. It became evident that, despite the great effort of the student divers of the Diving School, the propeller had not been sufficiently cleaned. There was nothing to be done.

By April 26, the negotiations on the fate of the islands were practically closed. COFUERSUB (Command of the Submarine Force) decided to send the San Luis to the “María” patrol zone, located north of the islands. It arrived there on the 28th, not without danger.

In the afternoon of the same day, with the deterioration of the military and political situation, the S-32 received the order to destroy any enemy target if it found it within the Exclusion Zone around the islands: “From COFUERSUB to San Luis. I cancel restrictions on the use of weapons. All contact is enemy.”

Even with all the problems mentioned and a broken firing computer (the brain of the submarine), the San Luis would cover itself in glory in the days to come. Admiral Brown would have been proud of this brave Navy lad.