Not even a damn military rebellion can organize a Peronist

Argentina en la Memoria

@OldArg1810

On June 9, 1956, the uprising of General Juan José Valle, and other soldiers and civilians who participated in the Peronist resistance, took place against the government of the Liberating Revolution, chaired by General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu.

In adopting its harsh anti-Peronist policies, the government had to take into account the possibility of counterrevolutionary violence. Above all because of the punitive measures he adopted against those whom he considered immoral beneficiaries of the "Peronist regime." The arrest of prominent figures, the investigation of people and companies allegedly involved in illicit profits, and the extensive purges that affected people who held union and military positions contributed to forming a group of disaffected individuals.

It was only logical to expect that some of them, especially those with military training, would resort to direct action to harass the government or overthrow it. Although incidents of sabotage carried out by workers were common in the months that followed Aramburu's inauguration, it was only in March 1956, as a consequence of the decrees that had declared the Peronist Party illegal, prohibiting the public use of Peronist symbols and other political disqualifications, when the conspiracies began.

A contributing factor, although ultimately misleading, may have been the government's decision, announced in February, to remove the death penalty for promoters of military rebellion from the military justice code. This punishment, which had been enacted by the Congress controlled by the Peronist Party, and which represented the interests of Perón, after the coup attempt of September 1951, led by General Menéndez, was eliminated from the military code on the basis that “ “It violates our constitutional traditions that have forever abolished the death penalty for political causes.” The facts would prove that this statement was premature.

The prominent figure in the conspiracy attempts against Aramburu was General (Retired) Juan José Valle, who had voluntarily retired after the fall of Perón and actively participated in the Military Junta of loyal officers that obtained Perón's resignation and handed over the government to General Eduardo Lonardi in September 1955.

Valle tried to attract other officials dissatisfied with the government's measures. One of those who chose to join him was General Miguel Iñiguez, a professional who enjoyed a great reputation and who was still on active duty, although he was on duty, awaiting the results of an investigation into his conduct as commander of the loyal forces in the Córdoba area, in September 1955. Iñiguez had not intervened in politics before the fall of Perón, but with a deep nationalist vocation, General Iñiguez joined General Valle in the reaction against the policies of the Aramburu government.

At the end of March 1956, Iñiguez agreed to act as chief of staff of the revolution, but a few days later he was arrested, denounced by an informer. Held under arrest for the next five months, he was able to escape the fate that awaited his companions.

The Valle conspiracy was, in essence, a military movement that attempted to take advantage of the resentment of many retired officers and non-commissioned officers as well as the unrest among active duty personnel. Although it had the cooperation of many Peronist civilians and the support of elements of the working class, the movement did not achieve the personal approval of Juan Domingo Perón, then exiled in Panama.

The sexual degenerate and his gang

The plan provided that military commando groups, mostly non-commissioned officers and civilians, would take over Army units in various cities and garrisons, take over media outlets and distribute weapons to those who responded to the proclamation of the uprising.

This included various terrorist attacks on public buildings, on national and provincial officials, on premises of political parties related to the Liberating Revolution, and on the editorial offices of various newspapers in the country. There was also an extensive list of military and political leaders, government sympathizers, who would be kidnapped and shot by the National Recovery Movement, whose homes were marked with red crosses at that time.

One of them was the one occupied by the socialist leader Américo Ghioldi and the teacher Delfina Varela Domínguez de Ghioldi, on 84 Ambrosetti Street, in the heart of the Caballito neighborhood. Other homes that were marked with red crosses were those of Pedro Aramburu, Isaac Rojas, the relatives of the deceased Eduardo Lonardi, Arturo Frondizi, Monsignor Manuel Tato, Alfredo Palacios, among others.

The government had only recently been aware that a conspiracy was being prepared, although it did not know precisely its scope or date. In early June, several signs, including the appearance of painted crosses, suggested that the uprising was imminent. For this reason, before President Aramburu left Buenos Aires accompanied by the Ministers of the Army and the Navy for a scheduled visit to the cities of Santa Fe and Rosario, it was decided to sign undated decrees and leave them in the hands of Vice President Rojas to to be able to proclaim martial law, if circumstances demanded it.

On June 8, the police detained hundreds of Peronist union soldiers to discourage mass worker participation in the planned movements. The rebels began the uprising between 11 p.m. and midnight on Saturday, June 9, gaining control of the 7th Infantry Regiment based in La Plata, and temporary possession of radio stations in several cities in the interior. In Santa Rosa, province of La Pampa, the rebels quickly took over the military district headquarters, the police department, and the city center. In the Federal Capital, loyal officers, alerted hours before the imminent coup, were able to thwart in a short time the attempt to take over the Army Mechanics School, and its adjacent arsenal, the Palermo regiments, and the Field Non-Commissioned Officers School of May.

Only in La Plata were the rebels able to take advantage of their initial victory, with the help of the civilian group, to launch an attack against the headquarters of the provincial police and that of the Second Infantry Division. There, however, with reinforcements from the Army and Navy that came to support the Police, the rebels were forced to withdraw from the regiment's facilities where, after attacks by Air Force and Navy planes, they surrendered to 9 in the morning of the 10th. The air attacks on Santa Rosa, capital of La Pampa, also ended in the surrender or dispersion of the rebels, more or less at the same time, therefore the rebellion ended up being a failure.

General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, back in Buenos Aires after his brief visit to Santa Fe and Rosario, gave a speech on the National Network, in which he spoke about the events that occurred during the early hours of June 9.

The June 9 insurrection was crushed with a harshness that was unprecedented in the last years of Argentine history. For the first time in the 20th century, a government ordered executions when repressing an attempted rebellion. Under the provisions of martial law, proclaimed shortly after the first rebel attacks, the government decreed that anyone who disturbed order, with or without weapons, would be subjected to summary trial. Over the next three days, twenty-seven people faced firing squads.

During the night of June 9 to 10, when nine civilians and two officers were executed, the rebels still dominated a sector of La Plata and the possibility of workers' uprisings in Greater Buenos Aires and other places could not be discounted. Those first executions were, according to the government, an emergency reaction to frighten and prevent the rebellion from turning into a civil war. This would explain the government's speed in authorizing and making public the executions, a speed that was demonstrated in the lack of any kind of prior trial, in the inclusion, in those who faced the firing squads, of men who had been captured before proclaiming themselves martial law, and in the confusion of the communiqués during the night of June 9 to 10.

During that night, they began to exaggerate the number of rebel civilians shot and erroneously reported the identity of the executed officers, to instill fear in the rebels and prevent them from taking to the streets to try to participate in the movement.

On the afternoon of the 10th, a massive demonstration took place in the Plaza de Mayo, which gave rise to scenes of joy and relief, as anti-Peronist crowds flocked to the Plaza de Mayo to greet President Aramburu and Vice President Rojas, and ask punishments for nationalist/Peronist rebels.

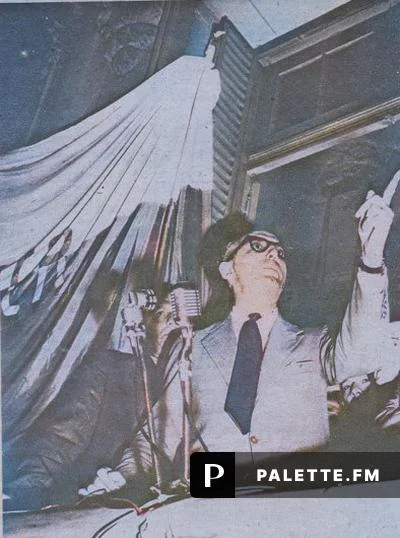

There, Admiral Isaac F. Rojas gave a speech from the balcony of the Casa Rosada:

Similar scenes, although with the roles reversed, had occurred in the past, when Peronist crowds demanded revenge against the rebels in September 1951 and June 1955. Only this time the government paid more attention than Perón to the cry for blood. After this act in Plaza de Mayo, Vice President Rojas, the entire Military Consultative Board, Aramburu and the three military ministers, made the disastrous decision to shoot the prisoners who had participated in the revolution against the government.

Against the advice of some civilian politicians, including some members of the Advisory Board, who urged an end to the executions, including a delegation formed by Américo Ghioldi and other members of the Advisory Board who went to the Government House, to request clemency and that the executions and attempts of some generals who opposed the executions be put to an end by calling Arturo Frondizi to put pressure on the authorities, and even though officers who made up the martial courts recommended that the rebels be subjected to military justice ordinary, the members of the de facto government resolved to continue applying the punishments provided for in martial law.

By making that decision, they persuaded themselves that they were setting an example that would increase the authority of the government and discourage future attempts at rebellion, thus preventing the loss of more lives. It is not known whether the Military Junta, at the June 10 meeting, took into account the fact that the majority of those already executed were civilians and that if the executions were suspended, the military leaders would suffer lighter punishments than those civilians. The truth is that the Military Junta rejected the suggestion of the commander of Campo de Mayo, Colonel Lorio, in the sense of limiting the pending executions to that of one or two lower-ranking officers.

Admiral Rojas strongly opposed making exceptions for the most senior officers, considering that this was a violation of ethics that “history” would not forgive; He preferred to suspend all executions rather than take any measure that would allow military leaders to escape the punishment imposed on those who had followed them. Ultimately, the Military Junta assumed direct responsibility for ordering the execution, over the next two days, of nine officers and seven non-commissioned officers.

On June 12, Manrique went to look for Valle, convinced that the shootings would be interrupted, and took him to the Palermo Regiment, where they interrogated him and sentenced him to death. Aramburu was convinced of doing so and said that "if after we have shot non-commissioned officers and civilians we spare the life of the person most responsible, a general of the Nation who is head of the movement, we are creating a terrible precedent; it will seem that the law It is not the same for everyone and that nothing happens between friends or similar hierarchies; the idea that the law applies only to the unhappy will be consolidated.

At eight at night they told Valle's relatives that he would be executed at 10. His daughter went to ask Monsignor Manuel Tato, deported to Rome in June 1955 during the conflicts between Perón and the Catholic Church and who was targeted for Valle's movement, to do something. Tato spoke with the Apostolic Nuncio, who telegraphed the Pope to ask Aramburu for clemency. But the request was denied. Valle said goodbye to his daughter and gave her some letters, including one addressed to Aramburu in which he said "You will have the satisfaction of having murdered me (...) I retain all my serenity in the face of death. Our material failure is a great moral triumph (...) As a Christian, I stand before God, who died executed, forgiving my murderers."

Shortly after, several sailors took him to an internal courtyard and shot him there. Moments after Valle's execution, the government suspended the application of martial law, bowing to increasing pressure from civilians and the military demanding an end to executions.

The political parties grouped in the National Advisory Board supported the government against the uprising. There was a secret meeting of the Advisory Board, on June 10, in which everyone said that they agreed with what was decided and what was resolved was support for the government. There was nothing related to the executions. Only Frondizi demanded to Aramburu, the next day and in his personal capacity, that civilians not be shot.

Américo Ghioldi, who had sought to stop the executions, wrote an article for the newspaper La Vanguardia in which he developed a justification for them, after learning that General Valle's uprising sought the execution of the socialist leader himself, saying: "The milk of mercy. Now everyone knows that no one will try, without risking life, to alter the order because it means preventing the return to democracy. It seems that in political matters, Argentines need to learn that the letter in blood enters.

Juan Domingo Perón, in a letter to John William Cooke from his exile, was highly critical of the Valle uprising and blamed several of the members of the attempted revolution for betraying him during the events of September 1955, saying: "The frustrated military coup It is a logical consequence of the lack of prudence that characterizes the military. They are in a hurry, we do not have to be in a hurry. Those same soldiers who today feel plagued by the injustice and arbitrariness of the dictatorial scoundrel did not have the same decision. September 16, when I saw them hesitate before every order and every measure of repression of their comrades who today put them to death (...) If I had not realized the betrayal and had remained in Buenos Aires, they themselves "They would have killed me, if only to make merit with the victors."

The first to promote the memory of "the martyrs of June 9" would be the different neo-Peronist groups, such as the Popular Union of Juan Atilio Bramuglia, who would campaign in 1958 against Perón's order to vote for Arturo Frondizi in the presidential elections of this year.