Beagle Crisis: The Fleets Face Off in the Southern Sea

By Esteban McLaren for FDRA

On December 22, 1978, D-Day, coordinated military actions along the borders with Chile would have commenced as part of Operation Sovereignty. It is difficult to determine with certainty which of the planned actions would have officially initiated the war, but it is clear that a simultaneous assault on at least four fronts would have taken place. The primary front would have been the naval battle and landing in the Beagle Channel, where the Argentine Navy's Marine Corps (IMARA) would have deployed troops to the Lennox, Nueva (already occupied by Chilean Marine Corps, CIM), and Picton Islands.

The purpose of this article is to explore an alternative history scenario. The war never took place, but what would have happened if Argentina had not accepted papal mediation?

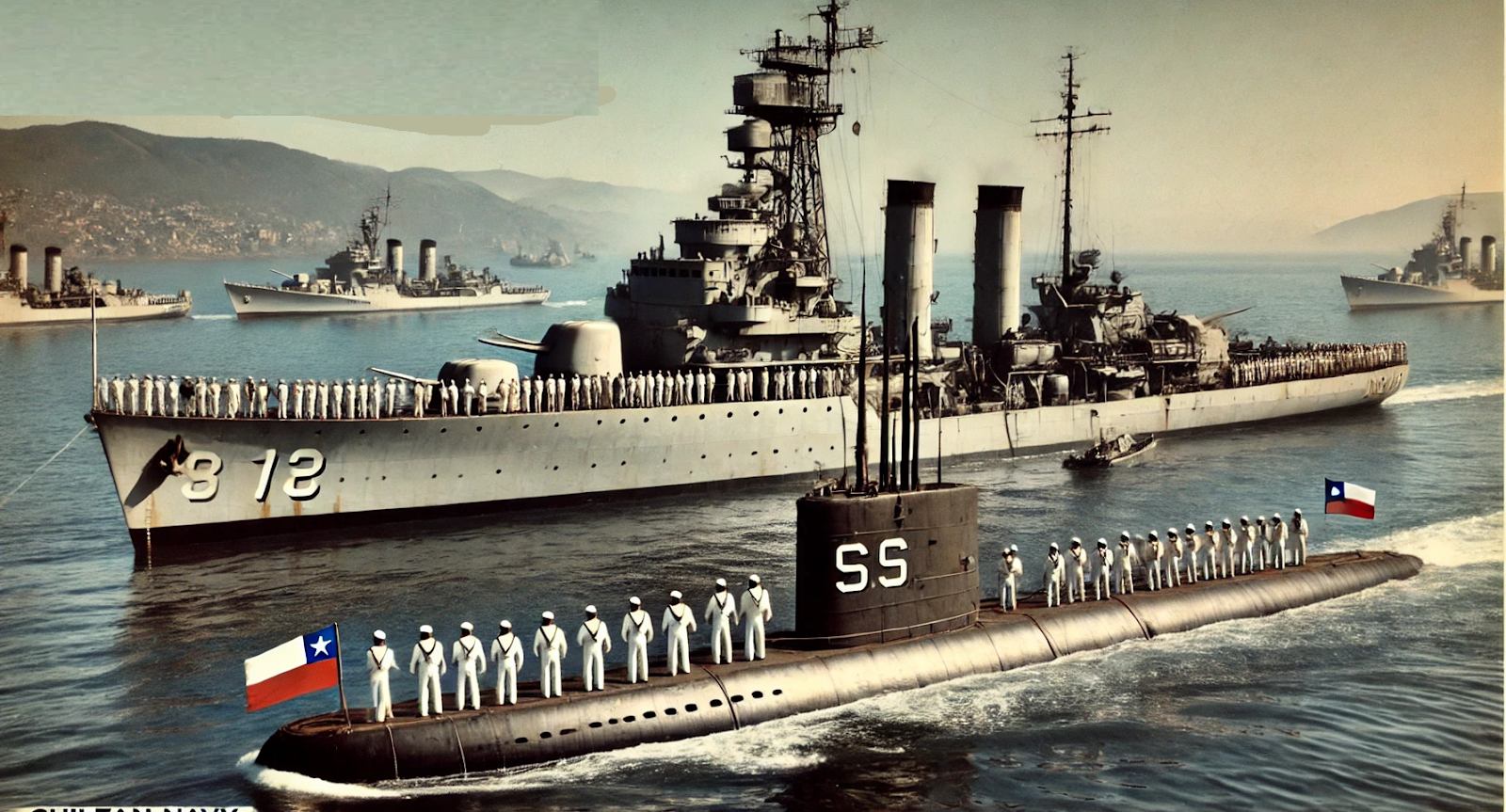

In December 1978, tensions between Argentina and Chile over the sovereignty of the Picton, Lennox, and Nueva islands in the Beagle Channel reached a critical point. Diplomacy had failed, and both countries were preparing for armed confrontation. The Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR), with its powerful combination of aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines, was preparing to face the Chilean Navy (ACh), a well-equipped force but at a numerical and technological disadvantage. Chilean authors speculate that in terms of infantry, Argentine forces roughly doubled the Chileans in size; in terms of armored vehicles, the ratio was 5:1; for aircraft, 3:1; and in naval strength, Argentina was slightly superior in some aspects (surface combatants), decisively superior in others (submarines operating in the area), and qualitatively unmatched in yet another (aircraft carriers).

Order of Battle as of December 20, 1978

Chilean Navy (ACh)

Main Ships:

- Tre Kronor-class light cruiser: Almirante Latorre.

- Brooklyn-class light cruiser: Capitán Prat.

- Almirante-class destroyers: Almirante Riveros, Blanco Encalada, and Cochrane.

- Leander-class frigates: Almirante Williams, Almirante Condell, and Almirante Lynch.

- Fletcher-class destroyers: Blanco Encalada (DD-14) and Cochrane (DD-15).

- Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer: Ministro Portales.

Submarines:

- SS Simpson, the only operational submarine, as the Oberon-class submarines were undergoing major maintenance.

Naval Aviation:

- AS-332 Super Puma helicopters.

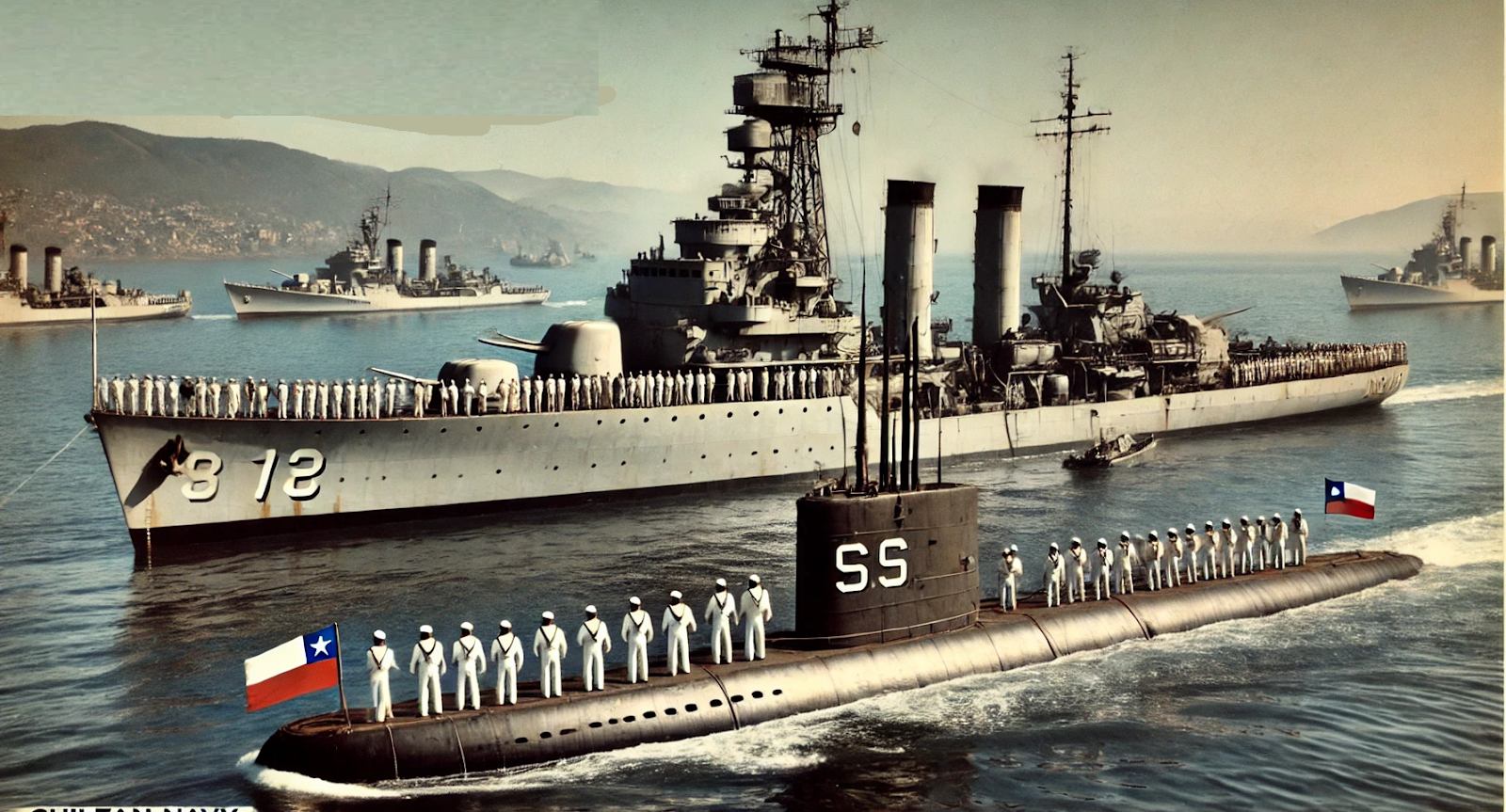

Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR)

Main Ships:

- Aircraft carrier: ARA Veinticinco de Mayo.

- Brooklyn-class cruiser: ARA General Belgrano.

- Type 42 destroyer: ARA Hércules.

- Gearing-class destroyer: ARA Py.

- Allen M. Sumner-class destroyers: ARA Comodoro Seguí, ARA Bouchard, and ARA Piedrabuena.

- Fletcher-class destroyers: ARA Rosales (D-22), ARA Almirante Domecq García (D-23), and ARA Almirante Storni (D-24).

- A69-class corvettes: ARA Drummond and ARA Guerrico.

Submarines:

- ARA Santiago del Estero, ARA Salta, ARA San Luis, and ARA Santa Fe.

Naval Aviation:

- 8 A-4Q Skyhawk aircraft aboard the carrier, with one on 24/7 interceptor alert on the flight deck. The interceptor on deck intercepted a CASA 212 maritime patrol aircraft stationed at Puerto Williams twice.

- SH-3 Sea King helicopters.

2. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Both Fleets

Chilean Navy (ACh)

Qualitative:

- High defensive capability with frigates equipped with Exocet missiles.

- Limited submarine capacity, with only one operational submarine.

- Good coordination between surface and air units.

Quantitative:

- 2 light cruiser

- 3 frigates

- 6 destroyers

- 1 operational submarine

Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR)

Qualitative:

- Air superiority with the aircraft carrier Veinticinco de Mayo.

- Greater submarine capacity with 4 operational submarines.

- High force projection capability with modern destroyers and frigates.

Quantitative:

- 1 air carrier

- 1 light cruiser

- 8 destroyers

- 2 missile corvettes

- 4 submarines

Conflict Escalation

The conflict did not de-escalate; on the contrary, it worsened. The Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR) decided to launch an attack on the Chilean Navy, which quickly set sail from Valparaíso heading south toward the Beagle Channel. The last detected position of FLOMAR was 120 miles (some sources cite 193 miles) southwest of Cape Horn, preparing to support Operation Sovereignty, whose primary objective was the amphibious landing and capture of the Picton, Lennox, and Nueva islands.

Capabilities Analysis

Chilean Navy (ACh)

The ACh possessed a light cruiser, destroyers, and frigates, all equipped with anti-air and anti-submarine defense capabilities. However, operational issues with the SS Simpson left the fleet without effective submarine coverage, a critical disadvantage in modern naval warfare.

Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR)

FLOMAR, on the other hand, had the advantage of the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo, which provided air superiority with its A-4Q Skyhawks. The modern destroyers and multiple operational submarines gave FLOMAR a robust capacity for both defense and attack.

Key Points of Advance and Refuge Locations for the Chilean Navy (ACh)

To reach the Beagle Channel, the Chilean fleet would advance southward from Valparaíso, passing through Puerto Montt, the Chacao Channel, the Gulf of Penas, Bahía Inútil, and the Strait of Magellan, before heading toward the Beagle Channel. If refuge were needed, Chilean fjords such as the Última Esperanza Fjord, Quintupeu Fjord, Aysén Fjord, or Comau Fjord would serve as strategic locations to hide and launch counterattacks.

Quintupeu and Comau Fjords

Última Esperanza Fjord or Sound

Final Approach to the Beagle Channel (or Cape Horn)

The upper map shows the route of the Chilean fleet according to official Chilean and Argentine bibliographies.

Note that the Chilean fleet’s course passed over the position of the ARA Santa Fé submarine because it had detected them precisely days before December 21. In other words, the enemy fleet had already been detected and followed by a submarine of the Argentine Submarine Force (CFS). The fleet was heading south of Cape Horn to combat stations, with two ships anchored side by side, awaiting orders to attack. The ships were arranged in this manner to allow for personnel exchange and social interaction while waiting (Arancibia Clavel & Bulnes Serrano, 2017). We will return to this point later.

Detection and Engagement Strategies

The Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR) would employ its S-2 Tracker and P-2 Neptune aircraft for reconnaissance missions (as they would successfully do four years later in the Malvinas), and the A-4Q Skyhawks for attacks, while Argentine submarines would ambush Chilean ships at critical points in the Strait of Magellan and the Drake Passage. FLOMAR’s destroyers and frigates would provide fire support and anti-aircraft defense to protect amphibious and heliborne assault operations.

Once again, it is enlightening to refer to the "official" account of the Chilean fleet’s movements (Arancibia Clavel & Bulnes Serrano, 2017). In this text, it is detailed how Chilean officers trained on a land-based simulator (this is not a joke) called

Redifon, which consisted of interconnected cubicles simulating ships, and practiced maneuvers in the basement of the Tactical Training Center of the Naval War Academy in Valparaíso. Merino and López, practicing on this analog simulator, tried various attack combinations on the FLOMAR and concluded that they had to achieve "control of the sea," aiming for a decisive naval battle in the style of Mahan. The outcome of these exercises determined an optimal attack formation where "

all missile-equipped ships would go ahead, with gunnery ships behind" (p. 86). I don’t understand why the Redifon was even required for something that seems like common sense. Or was there perhaps some logic to sending the gunships first (

Prat, Latorre) and the missile ships behind (

Almirante-class, Leander-class)?

FLOMAR, on the other hand, "lacked" such a simulator simply because the crews spent most of the naval year on board, maneuvering with real ships in real time and facing real problems. Approximately two-thirds of the year, the crews remained on board—a fact anyone with relatives in the Argentine Navy at that time can corroborate. Many sailors during this golden era of the Argentine Navy only met their children when they were 8 or 9 months old, as their life at sea prevented earlier visits. The distance between both fleets, beyond the geographic one, was astronomical.

Analysis of the Clash of Forces

Within the framework of the 1978 Beagle Crisis, tensions between Argentina and Chile reached a critical point, bringing both nations to the brink of armed conflict. Operation Sovereignty, planned by Argentina, had as its primary objective the amphibious landing and capture of the Picton, Lennox, and Nueva islands, located in the Beagle Channel. This operation was to be conducted under strong naval and air cover provided by the Argentine Fleet (FLOMAR).

Preparations and Force Composition

By late December 1978, FLOMAR was fully equipped and ready for action. It had at its disposal the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo, a crucial asset that carried A-4Q Skyhawks and S-2 Trackers, providing both air interception and maritime patrol capabilities. The fleet also included several modern destroyers, such as the ARA Hércules (the only one equipped with medium range naval SAM like the Sea Dart), as well as frigates like the ARA Piedrabuena and ARA Espora. Additionally, Argentina possessed a significant submarine force with the ARA Santiago del Estero, ARA Salta, ARA Santa Fe, and ARA San Luis submarines.

The Chilean Navy (ACh), although smaller in number, maintained a robust defensive force. Its primary asset was the light cruiser CL-02 Capitán Prat and the still formidable Almirante Latorre, accompanied by frigates and destroyers equipped with MM-38 Exocet missiles. The Chilean fleet also included the submarine SS-21 Simpson, the only operational submarine at the time, as the other Oberon-class submarines were undergoing major maintenance.

Operation Development

The landing operation planned by Argentina focused on Isla Nueva, where it was known that around 150 Chilean marines were entrenched. The Argentine strategy was to land on the southern coast of the island, avoiding Chilean defenses in the north. To execute this, the amphibious transport ARA Cabo San Antonio would be employed, escorted by destroyers and frigates providing fire support and protection.

The Chileans anticipated a conventional landing on the islands, when in fact, the most likely scenario was that the occupation would be carried out via vertical assault using helicopters.

The final phase of FLOMAR’s approach was established with the Argentine fleet advancing from its last detected position, 120 miles south of Cape Horn, moving eastward toward the Beagle Channel. Meanwhile, the Chilean Navy (ACh) mobilized from Puerto Williams, heading toward the channel to intercept the Argentine forces. Here, two simultaneous courses of action can be evaluated: first, the main fleet moved toward the Drake Passage to engage FLOMAR in open waters; second, the smaller torpedo boats (Quidora, Fresia, Tegualda, and Guacolda) would confront the landing force.

Submarine Warfare

The book La Escuadra en Acción by Arancibia Clavel and Bulnes Serrano recounts the military and political activity during the conflict, with a focus on the Chilean Navy. Although the text is not highly technical regarding the means employed, it provides an interesting general description of the operations of the Chilean fleet in the south.

In this account, it is mentioned that the Chilean Submarine Force was composed of the Balao-class submarine Simpson (SS-21) and the modern, for the time, British Oberon-class submarines named Hyatt (SS-23) and O'Brien (SS-22).

According to this source, the O'Brien was in dry dock during the conflict, and the Hyatt had to interrupt its transit south and return to its base in Talcahuano due to a mechanical failure. The other Balao-class submarine, the Thomson (SS-20), is not even mentioned, possibly because it had already been decommissioned due to its age. In fact, both Brazil and Argentina had retired their submarines of this class in the early 1970s, after receiving the Guppy class.

Although the Simpson was technologically outdated for the circumstances, it managed to fulfill its mission. The old submarine had to surface frequently to recharge its batteries, dangerously exposing itself to Argentine radars and periscopes. It was photographed at least twice by Argentine submarines while on the surface. Due to its wear, it is not surprising that this operation had to be performed more frequently than usual. The Simpson was detected twice by Argentine submarines, which chose not to fire their torpedoes. Nonetheless, it is possible that its commander, Rubén Scheihing, attempted to attack despite his technological disadvantage.

Patrol Areas Assigned to the Argentine Submarines

Although the exact dates cannot be confirmed, the Guppy-class submarines were very close to engaging in combat, although fortunately, their commanders interpreted their orders with sound judgment. In mid-December, the Santa Fe submarine was patrolling the entrance to Bahía Cook at a depth of 50 meters. The sonar operators detected the sound of approaching warship propellers. The commander of the S-21 raised the combat alarm, the crew took their positions, and all torpedo tubes were prepared for launch. The propeller sounds grew in number, eventually forming what appeared to be "a fleet." The Chilean squadron sailed above the S-21, heading into the open waters of the South Pacific.

The sonar operators counted three, four, six... up to 13 ships. Some had "heavy" propellers, like cruisers, while most had "light" propellers, similar to those of destroyers.

However, the Chilean fleet was sailing without emitting signals, meaning they were not using active sonar on the escort ships. A fleet commander's decision to sail without emitting can have several justifications, such as not actively searching for submarines or preferring to be more discreet, as sonar emissions propagate over great distances and can be detected by submarine countermeasure equipment, revealing their course or trajectory.

It is not difficult to imagine the immense tension experienced by the crew of the Santa Fe. Suspended in silence dozens of meters below the Pacific, they awaited the Chilean fleet's actions, with weapons ready to launch if the right moment came to strike from a tactically advantageous position.

Ultimately, the Chilean fleet entered open waters, moving away from the S-21. Following his orders, the commander of the Santa Fe did not interpret the Chilean fleet's maneuver as a hostile act, especially at a time when there was no formal declaration of war.

This situation clearly shows that the ARA Santa Fe was aware of the Chilean fleet's position and, in the event of war, it would have been the first to launch torpedoes against the Chilean fleet.

Meeting and Engagement Point

The meeting point of the fleets would be near the Beagle Channel. FLOMAR had to face the threat of the ACh's MM-38 Exocet missiles, with a range of 35-40 km. There is a recurring narrative in dialogues, discussions, and exchanges with trans-Andean experts and novices alike that suggests a certain accounting of Exocets, leading to the assumption that a potential naval battle would "clearly" tip in favor of the ACh. At that time, Chile was thought to have 4 to 8 more missile launchers than the ARA. This is the denial of the evident Argentine advantage, as these opinion shapers tend to overlook the key assets of the ARA: its aircraft carrier and its four operational submarines. For greater clarity, the aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo provided Argentina with a significant advantage, enabling attacks from distances of over 200 miles (370 km). Another key factor, when compared with the experience in the Malvinas, is that the Argentine Naval Aviation had full experience in anti-ship attacks, and the bomb fuses would have been correctly adjusted to detonate on impact with the ships. Once the Chilean fleet was detected by the S-2 Tracker and P-3 Neptune aircraft, its position would be relayed to FAA airbases and the CFS submarines, and it would only be a matter of time to see who would arrive first to the hunt.

Landing and Engagement Scenarios

Chilean Fleet’s Approach to Stop the Landing

The Chilean Navy (ACh) would rapidly advance from Puerto Williams toward the Beagle Channel, deploying its frigates and destroyers to intercept and attack the Argentine landing forces. Fast attack craft would also be used to disrupt the landings and support vessels. The Chileans would launch Exocet missiles and use naval artillery to harass the landing craft. Additionally, they would coordinate air strikes from Punta Arenas using Hawker Hunter and A-37 Dragonfly aircraft. Entering the Beagle Channel is a losing strategy for either fleet due to restricted movement, sensor disruption caused by terrain clutter, and the consequent degradation in weapon performance.

FLOMAR’s Response to This Movement

In response to the Chilean approach, FLOMAR would deploy its A-4Q Skyhawks and S-2 Trackers from the aircraft carrier to conduct preemptive strikes against ACh units. Argentine submarines would patrol strategic areas to intercept Chilean ships. FLOMAR would use its air defense systems to intercept approaching aircraft and launch its own anti-ship missiles to neutralize key threats. Unlike the Chilean fleet, the Argentine Navy had an external attack element in the form of carrier-based aviation. The confined space of the channel would facilitate an air-naval attack and would have been ideal for a sequence of attacks followed by rearming to restart the cycle.

ACh Focuses on Seeking Out FLOMAR for Direct Defeat

Based on the cited literature, this was the path chosen by the Chilean Navy. If the ACh had decided to seek out and directly confront FLOMAR, they would have circled Navarino Island or approached via the Drake Passage toward Cape Horn (southeast route). They would coordinate with the Simpson submarine and aerial patrols to locate the Argentine fleet, launching missiles and naval artillery strikes as soon as they detected it. According to the same literature, the ARA Santa Fe was positioned beneath the fleet when it entered open waters, meaning the target was detected first. Again, in this scenario, the Argentine naval aviation would have encountered them halfway, in any case, forcing them to endure several waves of A-4Q Skyhawk attacks. What remained of these waves would be what could confront an intact FLOMAR. Checkmate.

FLOMAR Focuses on Seeking Out ACh for Direct Defeat

If FLOMAR decided to seek out and directly confront ACh, it would advance from its position south of Cape Horn toward the northeast. They would use their carrier-based aircraft for reconnaissance and attack, first launching repeated air strikes to sink or disable the main surface assets, followed by attacks to sink or damage various ships. They would then move closer to launch anti-ship missiles from their destroyers and frigates, coordinating strikes with their submarines.

Here we recall the ACh's "combat station" formation: the ships were anchored side by side to share the wait with social interaction and the exchange of supplies. If the ARA had launched its A-4Q Skyhawks while this formation was still in place, it would have greatly facilitated the effectiveness of the bombs. A single bombing run by three aircraft with three 450-kilogram bombs could have impacted two ships at a time, doubling their efficiency. Checkmate.

Roles of Naval and Military Aviation

Argentine Carrier-Based Naval Aviation:

- A-4Q Skyhawk: These aircraft would conduct interception and air superiority missions, as well as attacks on enemy ships to protect the landing forces. A total of 8 units were carrier-based.

- S-2 Tracker: These aircraft would perform maritime patrols, submarine detection, and coordination of anti-submarine and anti-ship attacks. 2 units were carrier-based.

- P-3 Neptune: Operating from land bases, these long-range aircraft had highly trained crews who conducted year-round missions in the Argentine Sea.

Naval Aviation Based in Río Grande:

- T-28 Fennec: These aircraft would perform close air support missions and ground attacks to cover the landing forces (deployed in Río Grande and Estancia La Sara). A total of 19 units.

- MB-326 Aermacchi: These aircraft would carry out interdiction and ground attack missions to support amphibious and land operations (Río Grande). The exact number of units is undetermined.

- T-34C Turbo Mentor: These aircraft would undertake light attack missions, logistical support, and supply transport. More than 12 units.

Chilean Military Aviation in Chabunco:

- Hawker Hunter: These aircraft would perform interception and air combat, ship attacks, and provide support to ground forces (6 units).

- A-37 Dragonfly: These aircraft would conduct ground attacks, close support, interdiction, and harassment of Argentine landing forces (12 units).

Argentine Military Aviation in Río Gallegos:

- A-4B/C/P Skyhawk: These aircraft would carry out attacks on ships and provide support to ground forces, as well as interception and air combat when necessary (12 units).

- Mirage IIIEA/Mirage 5 Dagger/IAI Nesher: More than 30 units of the three models combined.

- F-86 Sabre: These were pure interception fighters, deployed to engage the Hawker Hunters due to experience gained during the Indo-Pakistani wars. The exact number is unclear, but pilot reports suggest there were more than 4 units and less than 14.

- Their objectives were first to initiate bombings against military targets in the cities of Punta Arenas (Chabunco airbase) and Puerto Williams (Zañartú airfield) and to destroy the Chilean Air Force, using a technique very similar to that employed by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967. The same approach would be implemented across all active fronts.