Brown and Black Regiment

The Regiment of Brown and Black (Pardos y Morenos) was a military unit of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata that participated in most of the military campaigns of the Argentine War of Independence until its dissolution in 1816 due to the Battle of Viluma. It was made up of soldiers from the castes of free mulattoes and freed blacks.

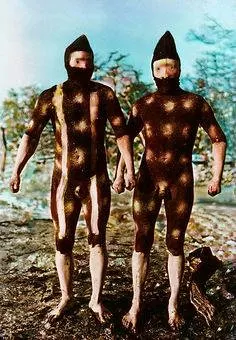

Uniform

The troops wore the uniform of the regiment consisting of a galley with a plume. Light blue jacket with bronze buttons and black collar and sleeves. Red sash and white pants with boots. They carried saber or flintlock rifle with bayonet. NCOs wore a red jacket with a white collar and sleeves.

May Revolution

Immediately after the May Revolution, on May 29, 1810, the First Government Junta of the nascent United Provinces of the Río de la Plata organized by decree the military units of Buenos Aires, raising veteran regiments of 1,116 squares to battalions of existing urban paid infantry militias. The Caste Battalion was also elevated to a Caste Regiment, but maintained its militia status.

By a decree issued on June 8, 1810, the Junta issued an order for the integration of the indigenous native companies that constituted the Battalion of Castes. This integration involved their incorporation into Regiments No. 2 Patricios (Patricians) and No. 3 Arribeños (Upstreamers), under the command of their existing officers. Consequently, the Regiment of Castas underwent a transformation and came to be recognized as the Pardos y Morenos (Brown and Black) Regiment. On June 19, 1810, the Junta appointed Martín Galain (1) as the lieutenant colonel and Miguel Estanislao Soler as the sergeant major of the regiment. (2)

A subsequent decree dated February 10, 1811, resulted in the renaming of the unit as the Regiment of Pardos y Morenos Patricios de Buenos Aires. Furthermore, another decree issued on October 4, 1811, bestowed upon the regiment the distinction of being classified as a veteran force. (3)

First Expedition to the Alto PerúOn June 14, the Junta issued an instruction to Juan José Castelli, a member, tasking him with assembling forces for the purpose of embarking on a military campaign to the interior provinces of the viceroyalty. This directive aimed to fulfill the mandate outlined in the Cabildo de Buenos Aires on May 25, which involved the formation of an army comprising 1,150 soldiers. Within this force were included 2 companies belonging to the Regiment of Pardos y Morenos.4 During its era, this assembled army was referred to as the Army of Peru or the Auxiliary Army of the Interior Provinces, but it is currently recognized more prominently as the Army of the North. The two caste companies advanced alongside the larger army through the regions of northern Argentina and Upper Peru, ultimately reaching the border of the Viceroyalty of Peru. On June 20, 1811, they actively participated in the pivotal Battle of Huaqui:

| The officers belonging to the Pardos and Morenos Patricios companies from that particular capital city have not only conducted themselves with the customary honor displayed in such situations during the action, but they have also subsequently exhibited a profound demonstration of their resilience in the face of adversity. Their unwavering subordination, dedication to duty, and evident commitment to serving their country have been undeniable. It is my duty to strongly commend Your Excellency to acknowledge their virtues as an act of justice and as a gesture of gratitude that they rightfully merit. Letter to the Junta, de Antonio González Balcarce, July 31th, 1811. |

After the defeat at Huaqui, the brown and brown companies withdrew with the army to Jujuy, where it was reorganized by the new commander Manuel Belgrano in 1812.

Liberation Expedition to Paraguay

On September 23, 1810, a contingent comprising 200 soldiers sourced from five infantry companies within the Buenos Aires garrison congregated at the encampment of San Nicolás de los Arroyos, among whom was a member with a brown complexion. This assembled force served as the nucleus for the Liberation Expedition to Paraguay, which was under the command of Manuel Belgrano. (5)

As they progressed through the Argentine Mesopotamia, the Brown (Pardos) Company operated within the 2nd Division, identifiable by its blue flag. Following the successful crossing of the Paraná River in the Misiones region, this company led the vanguard division and played an active role in the significant Battle of Paraguarí on January 19, 1811, as well as the consequential Battle of Tacuarí on March 9, 1811. Subsequent to the latter defeat, Belgrano retraced his steps across the Paraná River and established his headquarters in Candelaria. On March 21, 1811, he provided a comprehensive assessment of his forces, revealing that the Brown Company consisted of a captain, a lieutenant, three corporals, and a complement of 33 soldiers.

First Campaign to the Banda Oriental

In February 1811, 441 brown and brown soldiers sent from Buenos Aires under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Martín Galain, the 6th commander of the Brown and Brown Regiment, stationed themselves in Entre Ríos, on the western bank of the Uruguay River, with the mission of protect Belgrano's withdrawal from Paraguay and move the Banda Oriental. Those forces were in Santa Fe on January 9, 1811.

On February 28, 1811, the Creoles of the Banda Oriental insurrectioned against the viceroy, a fact known as the Grito de Asencio. Belgrano ordered Galain to cross the Uruguay River and take possession of Mercedes and Santo Domingo Soriano, who had declared themselves in favor of the Junta, for which he sent Soler with 50 brown and brown soldiers to position themselves in that town.7 A royalist squadron under the command of Juan Ángel Michelena entered the Negro River with 800 soldiers and intimated Soler's surrender. On April 4, 1811, the Combate de Soriano took place, which culminated in the triumph of Soler.

The revolutionary army under the command of Belgrano, which was returning from the Intendance of Paraguay and the Missions, crossed Mesopotamia and crossed the Uruguay River in Entre Ríos towards the Banda Oriental, where in April 1811 it established its headquarters in Mercedes:8 There the troops de Belgrano met with the eastern militias and the forces commanded by Rondeau.

The army advanced towards Montevideo and in the Second Division commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Agustín Sosa there were 450 men from the Pardos y Morenos Regiment. At the end of April Belgrano was replaced by Rondeau. After the triumph of José Artigas in the Battle of Las Piedras, the First Siege of Montevideo began on May 21, 1811, Rondeau arriving with the bulk of the troops on June 1 (including the brown and brown ones). On July 15, 1811, some soldiers from the regiment participated as volunteers in the Assault on the Isla de las Ratas.

Charge of the Brown and Blacks (Taringa)

After the Portuguese invasion of July 1811, the siege of Montevideo was lifted on October 12 and an armistice was signed on October 21 with Viceroy Francisco Javier de Elío. Fulfilling the agreement, the Buenos Aires troops evacuated eastern soil in December of that year and returned to Buenos Aires, while other forces crossed the Uruguay River, camping in Entre Ríos, the same as a large part of the people who carried out the eastern Exodus.

Second Campaign to the Banda Oriental

Since the Portuguese had not withdrawn from the Banda Oriental, and the hostilities with the royalists of Montevideo had resumed, in April 1812 the First Triumvirate demanded the immediate Portuguese withdrawal under threat of war. The Triumvirate sent Artigas 20,000 pesos led by Ventura Vázquez and the Regiment No. 6 of Pardos y Morenos under the command of Soler and made him head of operations. The Regiment of Pardos y Morenos had taken No. 6 on January 6, 1812, this number previously belonging to a regiment that participated in the expedition to Upper Peru and was reduced to a battalion.

On April 7, Artigas crossed the Uruguay River, returning to the Banda Oriental together with the Pardos y Morenos Regiment, highlighting parties towards the Cuareim, Negro and Tacuarembó rivers. On April 13, the Itapebí Grande Combat against the Portuguese took place, in which 400 infants from the Pardos y Morenos Regiment under the command of Soler participated.9 10 A new Portuguese attack forced Artigas' forces to cross the Uruguay River towards Between rivers.

In April 1812 the Triumvirate sent one of its members, Manuel de Sarratea, to take command of the army installed in Entre Ríos, sharpening the disagreements with Artigas. Among the forces that Sarratea separated from the Artigas camp at the end of 1812 was the Regiment No. 6 of Pardos y Morenos. When Sarratea went to Concepción del Uruguay, Soler stayed for a while in Salto Chico with his regiment.

In September 1812 the vanguard of Sarratea's army, commanded by Rondeau, crossed the Uruguay River and began the march on Montevideo, including the regiment Regiment No. 6 with 600 men. On October 20, 1812, the patriot army began the Second Siege of Montevideo. The Regiment No. 6 participated in an outstanding way in the Battle of Cerrito on December 31, 1812, having 43 dead and 65 wounded. For this triumph, on April 21, 1813, Soler received the orders of colonel of the Regiment No. 6 of Pardos y Morenos.

On March 17, 1814, 23 soldiers of the regiment commanded by second lieutenant Luis Antonio Frutos, participated in the capture of the Martín García island. The regiment remained besieging Montevideo until the fall of the plaza on May 23, 1814 at the hands of Carlos María de Alvear, being the first to enter the Citadel. In February 1815 part of the directorial troops evacuated Montevideo, including the brown and brown ones, being Soler appointed governor of that place on August 25, 1814, retaining the regiment headquarters. He served from August 1814 to February 25, 1815, when the troops of the United Provinces abandoned Montevideo, which remained in the hands of the Eastern militias of Artigas. In Buenos Aires the regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Mariano Díaz. On September 5, 1816, Brigadier Soler was appointed master barracks and major general of the Army of the Andes.

Second Campaign to Alto Perú (1812-1813). The triangles represent the battles: blue for the independence victories (Exodus from Jujuy, Tucumán and Salta) and red for the royalist victories (Vilcapugio and Ayohuma).

Second Campaign to Alto Perú (1812-1813). The triangles represent the battles: blue for the independence victories (Exodus from Jujuy, Tucumán and Salta) and red for the royalist victories (Vilcapugio and Ayohuma).Second Expedition to Alto Perú

When Belgrano took command of the Army of the North in April 1812, the Pardos y Morenos Corps under the command of Lieutenant Colonel José Superí, with 305 combatants, was in it.11 On December 10, 1812, reinforcements were received from Buenos Aires, between They were 70 or 80 brown and brown who joined the Corps of Castas, becoming the Battalion of Castas, under the command of Superí.

The battalion participated in the Combate de las Piedras on September 3, 1812, with 100 men, and in the Battle of Tucumán on September 24, 1812, commanding Superí one of the infantry columns. He also participated in the Battle of Salta on September 20, 1813.

After the defeat of Vilcapugio on October 1, 1813, Belgrano established his camp in Macha, trying to reorganize the army, which included 198 pardos and morenos under the command of Superí, but was defeated in the Battle of Ayohuma on November 14, 1813. , having to retrograde to Jujuy.

Third Campaign to Upper Peru (1815). The red triangle represents the only important battle of it, the royalist victory at Sipe-Sipe.

Third Campaign to Upper Peru (1815). The red triangle represents the only important battle of it, the royalist victory at Sipe-Sipe.Third Expedition to Alto Perú

On August 27, 1814, Regiment No. 6 (together with No. 2 and No. 9) was assigned to join the Auxiliary Army of Peru, continuing under Díaz's command since Soler's appointment as governor of Montevideo. The two battalions of the regiment traveled in 8 ships from the port of San Pedro, arriving in Santa Fe in the second week of September 1814. On September 21 they left Santa Fe, but on the way 126 men deserted, taking 42 rifles with them. They arrived at San Miguel de Tucumán on November 21, reduced to 549 soldiers and officers. In the first days of January 1815 the regiment moved to Huacalera in the Humahuaca ravine, where it arrived on January 16, remaining until March 20, 1815, when it headed for San Miguel de Chapaca. Arriving in Potosí on May 18, it continued on June 15 towards Yocaya and on August 16 the forces remained in the towns of Leñas, Culta and Sopollo, to leave for Ayohuma on September 17.

On October 2, 1815, Rondeau ordered Regiment No. 6 to go to Chayanta. On November 27, it was found in Sipe Sipe, where the Auxiliary Army was defeated on November 29, 1815 in the Battle of Viluma. Regiment No. 6 was in the reserve, but was involved in the escape of the Argentine infantry after the defeat, leaving many prisoners and many others dispersed.12

The dispersed met with the other troops in Yotala, retreating towards Tupiza and then towards Huacalera in the Humahuaca ravine, to later continue to Tucumán. On August 7, 1816, in Trancas, Rondeau was displaced and replaced by Manuel Belgrano at the head of the Army of the North. The army established itself in the Citadel of Tucumán, where it arrived on August 28. Belgrano distributed the remains of Regiment No. 6 between regiments No. 3 and No. 9, dissolving it.

Legacy

The 8 Mechanized Infantry Regiment (RIMec 8) based in Comodoro Rivadavia is considered heir to the history of the Brown and Black Regiment. At its headquarters there is a statue in homage to the soldier Falucho, an Afro-American who participated in the War of Independence in Peru in the Río de la Plata Regiment.

Mechanized Infantry Regiment 8, heir to that Brown and Black Regiment that crossed the Andes with San Martín. (Armando Fernández)

References

1. Biografías argentinas y sudamericanas. Volumen 2, pág. 689. Autor: Jacinto R. Yaben. Editor: Editorial "Metrópolis"

2. Biografía del brigadier argentino don Miguel Estanislao Soler. pág. 15. Autor: Pedro Lacasa. Editor: Imprenta "Constitución", 1854

3. Historia de la nación argentina: (desde los orígenes hasta la organización definitiva en 1862). Volumen 5, Parte 2, pág. 570. Autores: Academia Nacional de la Historia (Argentina), Ricardo Levene. Editor: Librería y editorial "El Ateneo", 1941

4. Archivo general de la República Argentina: Publicacion dirigida por Adolfo P. Carranza. Publicado por G. Kraft, 1894. pág. 78 y 79

5. Noticias históricas de la República Argentina: Obra póstuma. Escrito por Ignacio Nuñez, Ignacio Benito Nuñez, Julio Núñez. Pág. 173. Edition: 2. Publicado por Guillermo Kraft, 1898

6. Historia de Belgrano y de la independencia argentina, Volumen 1, pág. 375. Volúmenes 109-112 de Serie del siglo y medio. Autor: Bartolomé Mitre. Editor: Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires, 1967

7. Biografías argentinas y sudamericanas, Volumen 1, pág. 555. Autor: Jacinto R. Yaben. Editor: C. E. Escobar Tirado y D. E. Osorio Correa, 1938

8. Semblanza histórica del Ejército Argentino. Autor: Secretaría General de Ejército, Buenos Aires, 1981. pág. 29 y 30

9. El general Artigas y su época: Apuntes documentados para la historia oriental, Volumen 1. pp. 479. Autor: Justo Maeso. Editor: Tip. oriental de Peña y Roustan, 1885

10. Compendio de la historia de la República O. del Uruguay, Volúmenes 1-3. pp. 149-150. Autor: Isidoro De-María. Edición 7. Editor: Impr. "El siglo Ilustrado" de Turenne, Varzi y ca., 1895

11. Reestructuración del Ejército del Norte

12. Revista, Volumen 37, Números 432-437. Pág. 332. Autor: Círculo Militar (Buenos Aires, Argentina). Editor: Calle de Viamonte, 1937

Wikipedia