Thursday, March 13, 2025

Monday, March 10, 2025

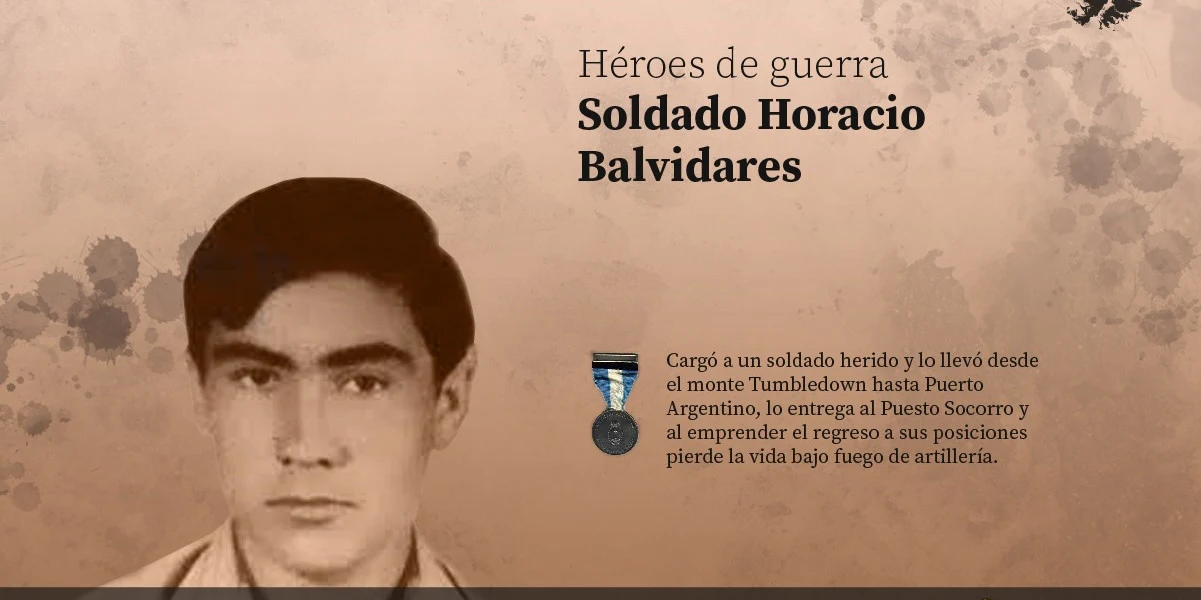

Malvinas: Soldier Horacio Balvidares and the Camaradie of War

Camaraderie and commitment in the fight for Mount Tumbledown

The little-known story of soldier Horacio Balvidares

On the night of June 13, the battle for Tumbledown, an Argentine defensive position in the path of the British advance towards Puerto Argentino, began. It was a battle that both sides remember as very hard, fierce, with a lot of automatic weapons fire and hand-to-hand combat.

View from Mount Tumbledown

The troops of the 5th Marine Infantry Battalion, the 4th Infantry Regiment and the 6th Infantry Regiment gave ample evidence of their determination and bravery in the face of an equally determined and brave enemy. For two days the Army men had been fighting at close range, and under the cover of their own Artillery they tried to recover physically while perfecting their positions.

English drawing about Tumbledown combat

The remnants of Company "B" of the 6th Infantry Regiment were waiting on Wireless Ridge for their turn to engage. They could not determine where the enemy would come from, but the sounds of the increasingly violent fighting made it clear that action would soon begin. They were ordered to block the flank of a Marine section on Tumbledown Mountain and began to advance in the darkness broken by flares.

A soldier is wounded in the legs and Private Adorno bravely goes forward to help him. Before reaching the position he is shot and seriously wounded in the arm, falling onto the rocks.

Private Horacio Balvidares assists him and carries him to the rear, on foot and with his companion on his shoulder, he travels kilometers from Tumbledown to the entrance of the town of Puerto Argentino. There they are met by a nurse who had gone ahead.

After handing over his wounded comrade and despite having reached an area far from the combat, with greater safety, he turned around and began to return to his section's positions, knowing the danger of crossfire and hand-to-hand combat, so it was that while returning he was mortally wounded by an enemy artillery shell.

A brave man who rescues another brave man. A soldier who returns with determination to the place of danger. Soldier Balvidares left an indelible mark among his comrades and saved a life that is still remembered, thanked and paid tribute to.

Brave, generous, good comrades and, above all, respectful of the oath to the flag of their country; that is what our men were like in Malvinas.

Friday, March 7, 2025

Tuesday, March 4, 2025

Malvinas: Tumbledown Night

Tumbledown: Blood and Courage

The Battle of Mount Tumbledown: A Nocturnal Clash in the Malvinas War

The Battle of Mount Tumbledown took place on the night of June 13–14, 1982, as part of the British campaign to recapture Puerto Argentino, the capital of the Malvinas Islands. It was a brutal, close-quarters fight in freezing, rugged terrain, pitting the Argentine 5th Marine Infantry Battalion (BIM 5) against a British force comprising the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards, the 1st Battalion 7th Gurkha Rifles, elements of 42 Commando Royal Marines, and supporting units like the Welsh Guards and Blues and Royals. The battle’s savagery stemmed from its nocturnal setting, the rocky landscape, and the desperate stakes for both sides.

The Setting: A Dark, Hostile Landscape

Imagine a moonless night, the Malvinas’ winter wind slicing through the air, temperatures hovering near freezing. Mount Tumbledown, a jagged, 750-foot-high ridge of crags and boulders, looms west of Stanley. Its slopes are slick with wet peat and frost, littered with rocks perfect for defensive positions. The Argentine 5th Marines, under Commander Carlos Robacio, are dug into trenches and sangars (stone shelters), their positions fortified with machine guns, mortars, and snipers. They’re cold-weather trained, hardened, and determined to hold this key height overlooking the capital. On the British side, soldiers huddle in the darkness near Goat Ridge, their breath visible as they prepare for a silent advance, weighed down by packs, rifles, and anti-tank weapons.

The Opening Moves: Diversion and Stealth

Picture the battle starting at 8:30 p.m. local time. A diversionary attack kicks off south of Tumbledown—four light tanks from the Blues and Royals (two Scorpions, two Scimitars) rumble forward, their engines roaring, accompanied by a small Scots Guards detachment. Their muzzle flashes light up the night, drawing Argentine fire. Meanwhile, the main assault begins from the west: three companies of Scots Guards—Left Flank, Right Flank, and G Company—move silently in phases, bayonets fixed, under cover of darkness. Mortar teams from 42 Commando set up behind, ready to rain shells, while naval gunfire from HMS Active’s 4.5-inch gun booms offshore, its explosions illuminating the horizon in brief, eerie flashes.

The Clash: Savage Close-Quarters Fighting

Visualize the moment the Scots Guards hit the Argentine lines. Left Flank Company, leading the assault, creeps undetected to the western slopes—then a Guardsman spots an Argentine sniper. A single shot rings out, followed by a volley of 66mm anti-tank rockets streaking through the dark, their fiery trails briefly exposing the enemy. The Guards charge, machine-gunners and riflemen firing from the hip, a chaotic line of muzzle flashes advancing over open ground. Argentine marines of N Company, entrenched with FAL rifles and MAG machine guns, return fire—tracers arc across the night, ricocheting off rocks. Grenades explode, showering shale and dirt; bayonets clash in brutal hand-to-hand combat. The air fills with shouts, screams, and the metallic clatter of weapons.

Halfway up, Left Flank’s 15 Platoon, under Lieutenant Alasdair Mitchell, takes heavy casualties—two men fall dead, others wounded, their blood staining the rocks. Right Flank Company, under Major John Kiszely, pushes east, meeting fierce resistance from Marine Sub-Lieutenant Carlos Vázquez’s 4th Platoon. Phosphorous grenades burst, casting a ghastly white glow, revealing Argentine defenders fighting from crag to crag. The Scots Guards lose eight dead and 43 wounded in this relentless grind, their red tunics (in spirit, if not literal uniform) soaked in sweat and blood.

The Gurkhas and Mount William: A Parallel Struggle

Now shift your gaze south to Mount William, a sub-hill held by the Argentine O Company. The 1st Battalion 7th Gurkha Rifles, held in reserve initially, moves in after Tumbledown’s summit is secured. Picture Gurkhas in camouflage, kukris gleaming faintly, advancing across a shell-pocked saddle under Argentine mortar fire from Sapper Hill. Eight are wounded as shells burst in the soft peat, muffling some blasts but not the chaos. They take Mount William by 9:00 a.m., their disciplined advance a stark contrast to the earlier melee, yet no less determined. Robacio would say "We're not afraid of them, they fell like flies". They were humans after all.

The Welsh Guards and Sapper Hill: Delayed but Deadly

Imagine the Welsh Guards, paired with Royal Marines, stuck in a minefield en route to Sapper Hill. Their frustration mounts as Argentine mortars pound them from above, one man killed earlier on a motorbike dispatch. They’re meant to follow the Gurkhas but are bogged down, their silhouettes barely visible in the pre-dawn murk, cursing the delay as shells whistle overhead.

The Argentine Retreat: A Final Stand

See the Argentine 5th Marines’ resolve crack as dawn nears. A sniper—perhaps Private Luis Bordón—fires at a British Scout helicopter evacuating wounded, injuring two Guardsmen before being cut down in a hail of Scots Guards gunfire. By 9:00 a.m., the Scots Guards hold Tumbledown’s eastern high ground, and the Gurkhas secure Mount William. Commander Robacio plans a counterattack from Sapper Hill, but his men—16 dead, 64 wounded—begin a disciplined retreat toward Puerto Argentino, marching in parade order, colors high, defiant even in defeat. Thirty Argentine bodies lie scattered across the battlefield, a testament to the fight’s ferocity. As soon as Robacio arrives, ask the Militar Governor Menéndez to send all of his men to the front. He was disregarded.

The Aftermath: A Hard-Won Victory

Envision the scene at sunrise: British troops, exhausted, consolidate their positions. The Scots Guards’ Pipe Major James Riddell stands atop Tumbledown, his bagpipes wailing “The Crags of Tumbledown Mountain,” a haunting tribute to the fallen. A Volvo BV-202 lies wrecked by a mine, its crew dazed. The British tally: 10 dead (8 Scots Guards, 1 Welsh Guard, 1 Royal Engineer), over 60 wounded. Medals—DSOs, Military Crosses, Distinguished Conduct Medals—will follow, but for now, the survivors catch their breath, the road to Puerto Argentino open at last.Saturday, March 1, 2025

Malvinas: The Fall of Gazelle XX-411 Under Güemes Team’s Fierce Fire

A Unique Photo… and Why It Matters

This photo is unique because the British NEVER show their dead—by law. In stark contrast, we have been bombarded with images of our fallen, displayed as trophies by them. To put it into perspective, the contingent of journalists embedded with British forces during the war was strictly forbidden from photographing bodies—unless they were already inside a body bag.

Now, let’s analyze this moment: May 21, 1982.

The wreckage belongs to the Gazelle helicopter of 3BAS, shot down by the brave men of Equipo Güemes (Güemes Combat Team), stationed in San Carlos. That day, they didn’t just take down this aircraft—they brought down three more helicopters. After the battle, they managed to break through the British encirclement and reached an estancia called Douglas, in the center of the island. There, on May 25, they formed up to honor Argentina’s national day before being airlifted to Puerto Argentino. Legendary footage by Eduardo Rotondo captures their arrival, where they were greeted with chocolates by Colonel Seineldín himself.

That same day, May 21, as British troops were landing, Sea King helicopters were transporting components of a Rapier surface-to-air missile launcher. One of these Sea Kings came under concentrated Argentine fire from a hill defended by Lieutenant Esteban (RI-25) and Sub-Lieutenant Vázquez (RI-12). The aircraft was forced into an emergency landing.

Then came the Gazelle XX-411, piloted by Sergeants Andy Evans (Royal Marines) and Eddy Candlish, rushing to assist. But as it approached, it was met with a relentless storm of Argentine gunfire. It crashed into the water—Evans perished, while Candlish managed to swim to shore, where kelpers helped him.

The British response was immediate. Another Gazelle, XX-402, armed with rocket pods, was dispatched to the battlefield. Lieutenant Ken D. Francis RM and his co-pilot, Corporal Brett Giffin, were at the controls. But once again, the Argentine riflemen struck with precision. The helicopter was torn apart by FAL fire, crashing at Punta Camarones, killing both men on board.

And that’s what we see in the photo: the shattered XX-402, guarded by a sentry. The lifeless bodies of the pilots lie on the ground.

Approaching rapidly, with his back to the camera, is Dr. Rick Jolly, the British medic who was later decorated by Argentina for saving the lives of countless soldiers—a true man of honor.

This image holds countless details of significance: the rocket pods, the antennas, the helmets… every element a silent witness to that day.

And there was yet another Gazelle—XX-412—that came in for a direct attack on our troops. It, too, was hit by Argentine fire. According to British reports, it managed to withdraw and was later repaired.

That afternoon, four British helicopters were knocked out of combat—by just a handful of brave men.

This isn’t just history. This is the untold story of courage, strategy, and sacrifice.

Source: Pucará de Malvinas

Wednesday, February 26, 2025

Sunday, February 23, 2025

Conquest of the Argentine Chaco

Conquest of the Argentine Chaco

The Argentine Republic at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century carried out the military occupation of the Central and Southern Chaco, which until then had been in the hands of indigenous peoples. The first military expedition took place in 1870 at the end of the War of the Triple Alliance and in 1917 the conquest of the territory was concluded.

The region between the Pilcomayo, Paraguay, Paraná and Salado rivers was inhabited at the end of the 19th century by indigenous peoples:

- Guaycurúes: mocovíes, tobas and pilagáes

- Mataco-mataguayos: wichís, chorotes and chulupíes

- Other: vilelas, tonocotés, tapietés, chanés and chiriguanos

|

| El Chaco |

Military expeditions and reconnaissance explorations

On April 16, 1870, Lieutenant Colonel Napoleón Uriburu left Jujuy with 250 men on mules, belonging to a regiment that he had formed with recruits from Salta and Jujuy and destined for the Orán border. He passed through La Cangayé, the old reduction of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores that had been founded in 1781 and abandoned in 1797 near the junction of the Teuco and Bermejo rivers, continued along the Bermejo and then entered the Chaco until reaching the Paraná River opposite Corrientes after 1,250 km traveled in 56 days. He subdued eleven chieftains and thousands of indigenous people who were assigned to the sugar cane harvest and reconnoitered a road to Corrientes. During this campaign, a detachment expelled a Bolivian squadron that was incurring in Argentine territory.On February 26, 1871, the ship Sol Argentino left Buenos Aires to explore the Bermejo River as far as the province of Salta and then returned to Buenos Aires in February 1872. During this trip, there were numerous clashes with indigenous people.

President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento created the Gran Chaco National Territory with its capital in Villa Occidental (today in Paraguay) on January 31, 1872, with Julio de Vedia as its first governor.

In 1872, Uriburu traveled through the Chaco to assist the steamship Leguizamón that was stranded in the Bermejo.

In 1875, Napoleon Uriburu, already as governor of Chaco, attacked the encampments of the chiefs Noiroidife and Silketroique, defeating them. That year, the American captain Santiago Bigney and six crew members of the barge Río de las Piedras were killed by the Tobas when they were sailing along the Bermejo River and trying to trade with them. To recover the boat and another that had helped it, on December 25, 1876, Navy Captain Federico Spurr entered the Bermejo River with the Viamonte, fighting in several actions against the Tobas, whom he defeated at Cabeza del Toba. The two boats had been sunk by the natives and were recovered by Spurr with part of the cargo, arriving at Corrientes on January 17, 1877.

On July 23, 1875, Commander Luis Jorge Fontana began a reconnaissance of the entrance to the Pilcomayo River, sailing 70 km along the river.

|

| Line Cavalry in the Southern Chaco Campaign, 1885 |

On August 29, 1879, Colonel Manuel Obligado left Reconquista with 150 men to reconnoiter a road and returned on October 12, after traveling 750 km, without fighting the natives.

On May 4, 1880, by order of President Nicolás Avellaneda, Major Luis Jorge Fontana left Resistencia with 7 officers, 30 soldiers, 8 natives and 2 civilians with the objective of reconnoitring a road that linked Corrientes with Salta. After 104 days he arrived at Colonia Rivadavia in Salta after traveling 520 km along the Bermejo and leaving a trail open. He defeated a group of Tobas who outnumbered him in a battle in which he lost an arm. Text of the telegram sent to Avellaneda:

I am in Rivadavia. The Chaco has been surveyed. I lost my left arm in a battle with the Indians, but I still have the other one to sign the map of the Chaco that I completed on this excursion.[1]On May 20, 1881, Colonel Juan Solá y Chavarría set out from the Dragones fort with 9 officers, 50 troops and 3 volunteers, with the objective of reconnoitering the interior of the area between the Pilcomayo and the Bermejo to the port of Formosa. From Fortín Belgrano he sailed along the Bermejo and, due to his delay in reaching his destination, the governor of Chaco, Colonel Bosch, sent 100 soldiers in his search. On September 3, Solá reached Herradura and from there he traveled by boat to Formosa.

On April 19, 1882, the Tobas murdered the French doctor Jules Crevaux and eleven of his companions near La Horqueta in the Pilcomayo. In mid-1882, Fontana, with the steamer Avellaneda and the launch Laura Leona, explored the Pilcomayo in search of Crevaux's remains, returning on September 18 without managing to find them. To punish the Tobas and Chiriguanos for the murder of Crevaux, Lieutenant Colonel Rudecindo Ibazeta left Dragones on June 11, 1883, leaving Dragones with 135 men. On August 10, they were attacked in the Pilcomayo by 650 partly mounted Indians, ending with the death of 60 of them. They returned on September 10 after having taught the Indians a lesson.

The French explorer Arturo Thouar made four expeditions in the Pilcomayo area in 1883, 1885, 1886 and 1892.

Victorica Campaign

In 1884, the Minister of War and Navy of President Julio Argentino Roca, General Benjamín Victorica, led a military campaign that aimed to extend the border with the indigenous people of Chaco to the Bermejo River, establishing a line of forts that would reach Salta.Five military columns set out from Córdoba, Resistencia and Formosa with the order to converge on La Cangayé, two squadrons were to go up the Bermejo and Pilcomayo rivers and the reserve was formed by part of the Marine Infantry Regiment at Fort General Belgrano. The campaign took place between October 17 and December 21, achieving its objectives and founding three towns (in El Timbó Puerto Bermejo, Puerto Expedición and Presidencia Roca were founded, and navigation on the Bermejo River was also opened.2

On August 21, 1884, a fleet under the command of Navy Sergeant Major Valentín Feilberg left Formosa, consisting of the Pilcomayo bomber, the Explorador tug, the Atlántico steamboat, the Sara barge and another smaller one. The objective was to explore the Pilcomayo and establish a fort at its mouth. This "Coronel Fotheringham" fort is the current city of Clorinda. They explored several branches of the river up to near Salto Palmar and returned to Buenos Aires on April 14, 1885. The Swedish naturalist and hydrological engineer Olaf J. Storm participated in the expedition.

On June 25, 1885, The steamer Teuco set sail from Buenos Aires under the command of Juan Page to explore the Bermejo, returning to Corrientes on October 3.

|

| Formosa At the End of thr 19th Century |

In August 1885 a fleet of three vessels sailed along the Bermejo under the command of Guillermo Aráoz, also exploring the Teuco River. The expedition continued in January 1886 to the San Francisco River under the command of second lieutenants Sáenz Valiente and Zorrilla.

On September 19, 1886, a squadron under the command of Navy Captain Federico Wenceslao Fernández, composed of the steamer Sucre and the barge Susana, set sail from Buenos Aires with the objective of exploring the Aguaray Guazú River and verifying its links with the Pilcomayo.

On March 12, 1890, the ships Bolivia and General Paz began a new exploration of the Pilcomayo under the command of frigate captain Juan Page (who died during the exploration), exploring the Brazo Norte.

On September 1, 1899, General Lorenzo Vintter began a military campaign in the southern Chaco, commanding 1,700 men from the Chaco Operations Division, made up of an infantry battalion, five cavalry regiments, and an artillery regiment. An attempt was made to peacefully convince the indigenous people that they should submit, but several battles took place and the border line was established at the Pilcomayo River. Advanced military posts were created, communicated by telegraph and a road. The campaign concluded with the effective military occupation of the Argentine Chaco, which was carried out with little indigenous resistance.

The Chaco Cavalry Division was dissolved in 1914, leaving only the 9th Cavalry Regiment in the area.

On December 31, 1917, the Conquest of Chaco was declared over, but in March 1919 a group of Paraguayan Indians, presumably Maká,3 attacked the Yunká fort (on the Pilcomayo, in Formosa), killing the entire garrison and the inhabitants who were there, except for a soldier named Barrios who had been evacuated to Formosa, sick with malaria. He lived for many years in Clorinda, where he died in the 1970s. Today the place is called Fortín Sgto. 1º Leyes, in honor of the leader who died in that attack.

Treaties

During the Spanish colonial period, several treaties were signed with the indigenous people of Chaco:41662: Peace treaty between the Tocagües and Vilos Indians and Santa Fe

1710: Treaty between Governor Urizar and the Malbalaes

17??: Treaty between Governor Urizar and the Lules

1774: Treaty between Matorras and Paykin

After 1816 in the Argentine colonial period:

1822: Peace treaty between Corrientes and the Abipones

1824: Perpetual agreement between Corrientes and the Abipones

1825: Treaty between Corrientes and the Chaco Indians

1864: Agreement between the Corrientes governor Ferré and the Chaco chieftains

1872: Peace treaty between the National Government and chieftain Changallo Chico

1875: Peace treaty between the National Government and chieftain Leoncito

References

[1] LA ARMADA ARGENTINA Y LAS CAMPAÑAS AL GRAN CHACO - 4

[2] Expediciones y Campañas al Desierto (1820-1917)

[3] El Río y la Frontera: Movilizaciones. Aborígenes, Obras Públicas y MERCOSUR en el Pilcomayo. Pág. 39. Autores: Gastón Gordillo, Juan Martín Leguizamón. Editor: Editorial Biblos, 2002. ISBN 9507863303, 9789507863301

[4] Tratados en Argentina

Wikipedia