Saturday, November 30, 2024

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Argentine Navy: Naval Traditions

Naval and Maritime Traditions: The Names of Argentine Warships

The names of Argentine warships are a naval tradition in their own right. The names San Martín and Brown have been used twelve times each to christen our ships, as many times as our national date: 25 de Mayo. Similarly, Libertad and Independencia have adorned sterns nine times each; 9 de Julio, eight times; and General Belgrano, six times.

This maintained tradition reflects the Argentine naval ethos, embodying its ideals, historic milestones, and heroes. The continuity in preserving and repeating these names ensures that the traditions they represent endure within the naval sphere and through time, transitioning from noble wood to sturdy steel with almost no interruption.

The old shipboard bulkhead clocks, once used to chime the hours in line with this system, are now valuable antiques cherished by collectors.

The general regulations currently governing the naming of Navy units were established by Permanent Order No. 1/81 of the Argentine Navy General Staff. This directive specifies the following categories of designations to be applied to ships inducted into the Argentine Navy:

[Include subsequent details from the original source, if applicable.]

Classification of Argentine Naval Ships

Major Warships: Named after national heroes or dates of great national significance.

Destroyers, Frigates, and Corvettes: Named after distinguished naval figures or traditional denominations of historically significant ships.

Submarines: Named after provinces and territories, preferably those beginning with "S" or located along the maritime coastline.

Minesweepers, Minehunters, Minelayers, and Mine Countermeasure Units: Named after provinces not covered in the submarine category.

Tenders, Salvage Ships, and Ocean Tugs: Named after sailors or civilians who have rendered valuable services to the Navy.

Training Ships: Reflect national ideals, names of former training vessels, or historic naval battles.

Scientific Research, Hydrographic, Oceanographic, and Buoy Tending Vessels: Named after cities with maritime ports.

Transport Ships, Assault Transports, Landing Ships, and Tankers: Named after geographic features such as channels or straits in Argentine waters, excluding Antarctic regions.

Workshop Ships, Dry Dock Ships, Hospital Ships, and Logistic Ships: Named after sailors or civilians distinguished for their scientific or related services, or those who died in service.

Icebreakers, Polar Ships, and Antarctic Stations: Named after geographical features in Argentine Antarctic waters or names historically linked to Argentine Antarctica.

Fast Attack Craft, Patrol Boats, and Torpedo Boats over 200 Tons: Given descriptive adjectives that represent a combative spirit or names of past units with significant historical relevance.

Fast Boats, Patrol Boats, and Torpedo Boats under 200 Tons: Named after riverfront cities or indigenous names from their operational zones.

Hydrographic Vessels: Named after seabirds native to Argentine maritime fauna.

Harbor Tugs and Dredges: Named after indigenous tribes, chieftains who supported national organization, or fish native to Argentine waters.

Yachts: Named after visible stars and constellations in the Southern Hemisphere or former notable yachts in Navy service.

Key Marine Infantry or Naval Aviation Units: Named after pioneers or prominent figures in their respective fields.

Naval Bases, Air Stations, Marine Infantry Bases, and Naval Arsenals: Named after geographical or historical sites, or distinguished naval figures who contributed to the Navy’s prestige and advancement, or naval battles.

Naval Schools and Academies: Named after distinguished figures within or associated with the Navy who promoted or brought prestige to it through intellectual or professional excellence.

The names of historic flagships, such as frigates or brigs now equipped

with missiles, not only revive past glories but keep the spirit of these

ships alive. This rich naval tradition is embodied in every exercise,

task, or mission requiring competition or emulation, and in combat, when

supreme sacrifice is demanded, they inspire the courage shown by their

namesakes in history.

Every ship, no matter how small or modest its mission, carries its own unique set of naval traditions. These traditions are cherished by successive commanding officers and crews, who take pride in maintaining and expanding them. Interestingly, such traditions often begin even before a ship officially joins the Navy, as illustrated by the following examples:

Coins at the Base of Masts or Keels

The custom of placing coins beneath the base of sailing ship masts during construction dates back to antiquity. While its exact origins are unclear, it is often attributed to the Vikings, who extended the terrestrial tradition of embedding silver coins in the foundations of new homes—particularly in hearths or chimneys—to ensure the happiness of the inhabitants. Another interpretation ties the practice to the Roman custom of placing a coin in the mouths of the deceased to pay Charon, the ferryman of the underworld, thereby symbolically settling the crew's fare should the ship sink.

In the Argentine Navy, this tradition has continued, although its exact starting point is unknown. Recent ships, such as Meko 360 and 140 destroyers and corvettes, had Argentine silver pesos (patacones) from the 1880s placed under the first keel plate laid in the shipyard. For Type 1700 submarines, a similar coin is used, but it is recovered after launch. As part of the ceremony, the youngest worker involved in the ship's construction presents the coin to the ship's sponsor, who then entrusts it to the ship’s commanding officer.

The Anchor

The term "anchor" originates from the Greek word for hook or grappling iron. Chinese scholars claim that anchors, known as Ting, were used as early as 2000 BCE, with the character for “stone” representing them in writing. Early anchors consisted of bags of sand or stone, later evolving into carved stone versions made by skilled stonemasons. The ancient Egyptian city of Ancyra is said to have derived its name from anchor manufacturing in local quarries.

For the Romans, the anchor symbolized wealth and commerce, while for the Greeks, it represented trust and security—a meaning that persists in heraldry today. Early Christians adopted the Greek symbolism, associating the anchor with steadfastness, hope, and salvation. This is reflected in ancient catacomb paintings featuring anchors resembling those in use today.

The Boatswain’s Pipe

This quintessential naval tool has been used aboard ships since the era of galleys and has served as a symbol of command. By the 18th century, it became emblematic of the British Admiralty. Made from noble metals such as silver or gold, the boatswain’s pipe was essential for issuing commands. Its sharp, piercing sound could be heard even during fierce storms, making it indispensable for coordinating maneuvers.

In Argentine training ships, this tradition persists, with all orders for maneuvers transmitted using the boatswain’s pipe. Admiral Guillermo Brown introduced its use in March 1814, formalizing the honors rendered with the instrument. Skilled boatswains often tune their pipes to produce harmonious tones.

One notable symbol of this tradition in the Argentine Navy is the gold boatswain’s pipe belonging to Boatswain Liorca. He famously rendered honors to President Julio A. Roca when the president boarded the corvette A.R.A. La Argentina. In gratitude, President Roca gifted him the pipe, which Liorca’s son, Subofficer Serapio Liorca, later donated to the National Naval Museum, where it is preserved today.

Gun Salute Tradition

The tradition of firing gun salutes as a sign of courtesy is an ancient international naval custom. Historically, firing salvos demonstrated peaceful intentions, often accompanied by additional gestures that left the ship temporarily defenseless, such as lowering sails, bracing yards, or shipping oars.

In the Argentine Navy, Admiral Guillermo Brown adhered to this tradition as early as 1814, honoring the international custom of gun salutes. The number of salvos fired has always been an odd number, reflecting an old superstition associating odd numbers with good fortune. In earlier times, the extended reloading time for cannons led stronger navies, such as the British, to demand that weaker nations fire the first salute. By the 20th century, this was replaced by the principle of state equality, with salutes being returned shot-for-shot.

The tradition of 21-gun salutes dates back to the early days, when the British Navy established seven cannon shots as their national salute, answered from shore with three shots for every one fired from the ship—21 in total. At the time, maintaining gunpowder quality aboard ships was more challenging than on land. As gunpowder and ship magazines improved, the number of shots exchanged between ships and shore became equal.

In the Argentine Navy, 21-gun salutes are reserved for the President of the Republic, as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. They are also fired upon arriving or departing foreign ports designated as "saluting stations," when affirming a ship’s flag, or during a vessel’s first arrival at an Argentine port. It is standard protocol to perform this salute only when the national flag is raised, with personnel rendering a military salute while the salvos are fired. At sea, if possible, the honors detail assumes its role during the salute.

The Ship’s Bell

The ship’s bell has been in use aboard vessels since the early 13th century, traditionally mounted on the quarterdeck. Its chimes were regulated by half-hour sandglasses until the mid-19th century, with the bell rung each time the glass was turned.

During each watch, the bell is rung at half-hour intervals, with an additional chime for every half-hour, culminating in eight bells at the end of the watch. The sequence then resets at the start of the next watch. The distinctive method of ringing the bell involves paired chimes rung quickly, followed by a pause before the next set, as illustrated:

- Three bells: rat-tata (pause) tat.

- Four bells: rat-tata (pause) rat-tat.

This unique cadence is an integral part of shipboard tradition, reflecting the long-standing maritime heritage shared across navies.

The Cap Emblem

The anchor in the emblem on our caps symbolizes the naval profession to which we dedicate our lives. The rope encircling and embracing it, firmly secured in its ring, represents our existence, signifying that all our thoughts and actions are fully subordinated to our vocation. Gold, the purest and most precious metal, signifies that purity in thought and deed must guide our actions.

The laurel, a timeless symbol of strength and the character of the victor, in this emblem signifies that our spirit, dedicated to the profession we have chosen, must triumph over the material temptations of indulgence and neglect. The Sun, the King of Stars crowning the emblem, represents the lofty vision, thought, and action that a Naval Officer must possess.

Thus, the emblem is the symbol of the high ideals to which we devote our lives. It is the crest of Naval Officers, the "Knights of the Sea," which must remain proud, upright, and triumphant in the battles fought within our consciences. In these contests, the reward for the victor is none other than the satisfaction of duty fulfilled with loyalty, honesty, sincerity, and selflessness.

Sunday, November 24, 2024

Malvinas: Battle Chronology

Thursday, November 21, 2024

Naval Aviation: The Captain Castro Fox Accident

Castro Fox's Accident

Memoirs of Captain (Ret.) VGM Rodolfo Castro Fox, Commander of EA33.

Sunday, August 9, 1981

That afternoon, under calm skies, I was catapulted from the deck in my A-4Q, 3-A-303. I was undergoing requalification, having already completed two arrestments in the 3-A-307 earlier that morning.

“Stable deck, wind at 28/30 knots.” The signal officer's voice came through the radio, relaying the conditions for my landing on the aircraft carrier 25 de Mayo.

“03, ball, three five,” I responded, acknowledging the yellow light indicator projected by the stabilized glide slope system on the port side of the ship. At the same time, I confirmed my fuel in hundreds of pounds.

Completing my turn into the final leg at 500 feet, I caught sight of the ship's white wake below and to my left, contrasting against a nearly calm, greenish-blue sea. Ahead, a thick yellow inverted “T” marked the start of the angled deck, positioned eight degrees off the carrier’s centerline. To the right, the “island,” crowded with platforms, antennas, and the ship’s smokestack, released a column of smoke aligned with the relative wind, running parallel to the deck’s axis.

My focus was split: keeping the “ball” centered with the green reference line flanked by guide lights, ensuring the angle-of-attack indicator in “Donna” showed a yellow light, and aligning with the deck’s axis, which slightly shifted to the right as the ship moved.

Gentle adjustments on the throttle and flight controls kept everything aligned, maintaining engine thrust between 80 and 90 percent of its 8,200 pounds of power. The ship's high stern swayed slowly as the sharp turbine whine was interrupted by instructions from the Landing Signal Officer on the radio.

Though I had over 250 arrestments, the concentration and tension remained the same. There’s no room for distraction; only after the flight can one relax, reliving and savoring this demanding and cherished activity of naval aviators.

The carrier rapidly grew larger; I crossed over the stern at 130 knots, with the “ball” centered, reaching the zone of the six arrestor cables. Just as I touched down, my left hand automatically pushed the throttle to 100 percent while my thumb engaged the dive brake switch, ready to take off again if the hook missed the cable.

The deceleration began immediately. I had caught the third cable, right on centerline, and my body was held back by the harness straps across my torso, while my head moved freely forward.

The Precise Moment When the 3-A-303 Breaks the Arresting Cable and Heads Toward the Sea

In that critical instant, the 3-A-303, having engaged the arresting cable, suddenly broke free. The snap was abrupt, and instead of decelerating as expected, the aircraft continued forward. The deck rushed past beneath me, and in those split seconds, I knew the plane was headed off the edge and toward the open sea.

With no time to lose, my reflexes kicked in. My hand was already at the throttle, pushing it to full power in an attempt to regain altitude. The aircraft barely cleared the edge of the flight deck, plummeting toward the water before the engine’s thrust began to pull it back up. That brief but intense moment, where I was suspended between sky and sea, brought every skill and ounce of training to the fore.

The nose of the aircraft, now lowered, shook with oscillating lateral movements due to the immense deceleration it was experiencing as the 14,500-pound plane came to a halt at a relative speed of 100 knots within less than 60 meters. Just in front of me lay the ocean, separated only by a few meters of deck.

Suddenly, at very low speed and reducing the throttle to minimum, my body pressed against the seatback, and my head jerked back into the headrest. The plane had freed itself from the arresting cable as it snapped, and it surged forward. Instinctively, I pushed the throttle to 100 percent—a habit from touch-and-go landings or "bolters" on the deck—believing I was gaining speed.

But this time, I didn’t have enough speed to take off again, as I had once done four years earlier in the same plane. I quickly reduced the throttle and applied right rudder to guide the plane toward the axial runway centerline, aiming to maximize the space to try to brake. There, I would have an additional 50 meters of deck, but the speed was too high, and the plane skidded leftward.

Over the radio, I heard the signal officer shouting, "Eject—Eject!" Instinctively, I pulled the lower ejection seat handle with my right hand. I felt a muffled explosion behind me as the canopy, propelled by the fired cartridge, detached and slid backward. I expected the seat’s rocket to fire next and propel me out—but the seat didn’t eject.

The plane continued its path toward the angled deck’s end; the nose wheel dipped into the edge, and the plane crossed over a 40 mm anti-aircraft mount, sharply turning left as the left wheel was the first to lose contact with the deck. The carrier’s deck disappeared from view; I was plummeting toward the sea from a height of 13 meters, inverted, strapped tightly to the ejection seat by upper and lower harnesses. Less than five seconds had passed since the cable snapped, and I was losing consciousness as we struck the water.

Every action and image from recognizing the emergency as the cable snapped is vivid to me, with time seeming to slow as if in slow motion, until the aircraft hit the sea at dusk.

It was only later that I regained consciousness, being airlifted in a Sea King helicopter to the Puerto Belgrano Naval Hospital, some 100 miles away. Tied to the stretcher, I wondered about my slim chances of surviving a water landing in the dead of night.

I only learned what happened after the crash from the accounts of those involved, as I have no memory of those moments. When the plane hit the water, nose down and inverted, the ejection seat fired, likely launching me like a torpedo toward the seabed, propelled by the rocket that ignited at that moment. Otherwise, I would have gone down with the plane to the ocean floor.

The condition of my left arm evidenced the force with which the seat left the aircraft. My left hand had been on the throttle—a critical mistake during ejection—and my forearm was crushed in the narrow space between the cockpit’s interior side and the side of the ejection seat. As a result, I suffered fractures to the ulna, radius, and humeral tuberosity, as well as a scapulohumeral dislocation.

The seat continued its sequence through the various explosive cartridges, releasing the harness around my torso, inflating the bladders to separate me from the seat, and deploying the pilot chute to extract the parachute. Had this sequence failed, I would have remained strapped to the seat and descended to the seabed.

Dressed as I was in an anti-exposure suit that trapped air between my body and the fabric, along with the rest of my flight gear—torso harness, survival vest, and dry anti-g suit—my body began a slow ascent to the surface due to positive buoyancy. Those who saw me surface after almost two minutes reported that I was paddling with my right arm. Immediately, an Alouette helicopter stationed for rescue, commanded by then-Lieutenant Commander Carlos Espilondo, approached my position. Two rescue swimmers dove into the sea, detached my parachute, and slipped the rescue sling under my shoulders.

They hoisted me up with the helicopter winch and began to transport me; however, I didn’t stay aloft for long. Unconscious and with a dislocated shoulder, my arms rose, causing the sling to slip, and I fell back into the sea. This time, the rescue swimmers had to reach my new position and pull me from beneath the surface, as my now-soaked gear no longer provided positive buoyancy and they hadn’t inflated my life vest.

They attached the sling to the carabiner on my flight suit, designed for such cases, and this time successfully lifted me into the Alouette.

When they placed me on the flight deck, their first move was to remove the water from my lungs. I was quickly transported on a stretcher via the forward elevator on the flight deck to the onboard surgical room.

On the way to the infirmary, I suffered my first cardiorespiratory arrest, from which they successfully revived me.

For a long time, I didn’t respond to external stimuli, and in the operating room, I experienced a second arrest, but again, the medical team managed to bring me back. Days later, the doctors asked if I remembered how they had revived me from these arrests; my denial brought them a sense of relief.

The diagnosis read like a list of battle wounds: multiple trauma, drowning-induced asphyxia, lung shock, cardiorespiratory arrest, cranial trauma with loss of consciousness, bilateral orbital trauma, radial and ulnar fractures, left rib fracture, anterior shoulder dislocation, submental, supra-auricular, and left eyelid wounds, bipalpebral hematoma, conjunctival hemorrhage, and multiple abrasions. This grim report was signed by Lieutenant Commander and Medical Officer Edgar Coria, who, along with the Naval Air Group’s medical team, treated me.

That night, I was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit at the hospital, where I remained for four days.

Around midnight, Commander Jorge Philippi and his wife Graciela called our apartment in Bahía Blanca to inform Stella of my accident and hospitalization. Months later, I would be the one to inform Graciela of her husband’s disappearance during the Malvinas conflict.

My appearance must have been quite unsettling, with swelling, bruises, stitches, and more. I realized this when visitors who weren’t medical staff would turn pale and quickly leave the ICU. The nurses, using various excuses, refused to provide me with a mirror despite my repeated requests.

Even days later, when I had been moved to a regular room, my children were visibly shaken upon seeing me. If any of them had thought about studying medicine, I likely discouraged that notion. According to specialists, factors that helped prevent neurological sequelae included the cold water and the fact that I had been breathing 100 percent oxygen during the flight. The A-4 lacks a demand system that mixes oxygen with cabin air; instead, it uses a liquid oxygen system with a converter and regulator that delivers pure oxygen.

Perhaps, “Tata Dios” hadn’t planned on calling my number that day—or St. Peter simply made a mistake with the list.

After overcoming the major risk of pulmonary or renal complications, the ordeal of recovering my left arm began. Pins were placed in both bones of my forearm, and I was fitted with a cast that I wore for over three months, constantly adjusted in posture and size.

Declared unfit for flight, I attended medical evaluations every two months, where they noted my recovery from various traumas, abrasions, and interstitial pneumonia, yet my left arm remained restricted in movement. I continued my duties as Deputy Commander at the squadron, but with envy as I watched my fellow pilots take to the skies.

Toward the end of the year, the awards for the 1980 weapons exercises were presented in a ceremony held at the Puerto Belgrano Naval Base Auditorium. I was called up to receive the La Capital of Rosario award for the highest annual individual score in air-to-air shooting among all attack squadron pilots. Seeing me with my arm in a cast, someone joked, “Imagine if he had both arms!”

Monday, November 18, 2024

Argentine Navy: ARA 25 de Mayo in the 1980s

Argentine Navy aircraft carrier ARA 25 de Mayo in operation in the 1980s

Poder Naval

Argentine Navy A-4Q fighters operating on the aircraft carrier ARA 25 de Mayo, circa 1980. At that time, the Argentine Navy had a more powerful GAE (Embarked Air Group) than the one on the aircraft carrier Minas Gerais. da Armada de Brasil, which operated only anti-submarine aircraft.

Originally built for the Royal Navy during World War II as HMS Venerable, this Colossus Class aircraft carrier was transferred to Argentina in 1969, where it was renamed in honor of the May Revolution of 1810, which marked the beginning of Argentina's independence process from Spain.

The main characteristics of the ARA 25 de Mayo were a displacement of approximately 19,900 tons at full load, a length of approximately 192 meters and a beam of 24.4 meters. With a top speed of about 24 knots (about 44 km/h), it was powered by 4 boilers with 40,000 hp (30,000 kW) steam turbines driving 2 shafts.

During the Malvinas War in 1982, the ARA 25 de Mayo's S-2 Tracker aircraft detected the main body of the British Task Force in the early hours of 2 May at about 200 miles away, but the ship was unable to launch its attack aircraft against British ships due to a lull.

Near the time of catapulting the aircraft for the morning attack, when a wind speed of 30 knots was needed, this was almost zero, so each A-4Q aircraft could take off with a single bomb or with fuel for a range of only 100 miles.

The ARA 25 de Mayo, at that time, could only reach 20 knots, an insufficient speed to produce the relative wind in the flight deck necessary to launch the aircraft with four Mk.82 bombs. The probability of impact would be insignificant, not justifying the attack. The mission was aborted.

SOURCE : @MarianoSciaroni, in X

Friday, November 15, 2024

Malvinas: A Study Case (1/3)

Malvinas: A Study Case

Part 1/3

Sigue en Parte 2 - Parte 3

By Harry Train,

USN Admiral

This analysis covers the Malvinas/Falklands Conflict chronologically, from the preceding incidents to the conclusion of the Battle of Puerto Argentino/Port Stanley. Strategically, it examines the conflict across general, military, and operational levels, taking into account each side’s operational concepts and strategic objectives. This approach provides a balanced view of the strategies and tactics employed, highlighting the complexities faced by both Argentina and the United Kingdom in one of the most pivotal conflicts of the late 20th century in the South Atlantic.

In the Southern Hemisphere, it’s known as the Falklands Conflict; in North America and Europe, the South Atlantic Conflict. The British refer to it as the "South Atlantic War."

At the National Defense University in the U.S., where I teach the Final Course for newly promoted generals and admirals, we cover two case studies of special interest: one is the Grenada crisis, which we study and discuss to learn from the mistakes made by U.S. forces, despite achieving objectives. Many of my students, having fought in Grenada, tend to justify their decisions emotionally, rationalizing choices that, in hindsight, were suboptimal.

For this reason, we teach a second case where the U.S. was merely an observer: the Falklands Conflict. Rich in political-military decisions and full of errors and miscalculations on both sides, this case offers our generals and admirals an opportunity to examine a complex diplomatic framework and see how political factors, some still overlooked, led to the failure of diplomacy and ultimately to war. This conflict also allows for the analysis of an unprecedented military-political phenomenon: one side still operated under crisis management rules while the other was already at war.

This case also lets U.S. generals and admirals consider the benefits of joint defense structures by examining Argentina's new joint command system, which was joint in name only. The conflict also held lessons for the U.S. Congress in organizing our national defense and showed the impact of chance on the outcome of war.

— Would the results have been different if British television had not mistakenly reported the deployment of two nuclear submarines from Gibraltar towards South Georgia on March 26?

— Would the results have been different if the weather had not been calm on May 1?

— Would the results have changed if the 14 bombs that penetrated British warships had exploded?

— Would the outcome have been different if the Argentine Telefunken torpedoes had functioned properly?

— Would the British response have been the same if not for the coal miners' strikes in Britain?

The conflict also provides a retrospective view of crucial decisions, such as Argentina’s failure to extend the Port Stanley runway to accommodate A-4s and Mirages, the lack of heavy artillery and helicopters delivered to the Islands between April 2 and 12, the division of Argentine forces between East and West Falklands, the decision not to exploit British vulnerability at Fitz Roy and Bluff Cove, and the British decision to attack the cruiser General Belgrano.

We also examine how the land war might have unfolded if the Argentine forces from West Falkland had been in San Carlos, forcing the British to establish their beachhead on West rather than East Falkland.

My vantage point during the conflict was as Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet and Supreme NATO Commander in the Atlantic. My role was solely observational, overseeing a conflict between two valued allies. As my friend Horacio Fisher, then an Argentine liaison officer on my staff, can attest, we received little information on the war’s progress at my Norfolk command. There, our assessments foresaw an Argentine victory until the conflict’s final weeks, as we were unaware of certain pivotal decisions that later proved us wrong.

What I’ll share with you is my personal view of the Falklands Conflict, a product of months of studying reports, records, and interviews with the main leaders from both sides. This study has been challenging, as reports and interviews often reflect conflicting perspectives on key political and military events. This is in itself instructive, illustrating the "fog of war." In my research, I’ve had full access to Argentine and British leaders, documents, and post-conflict analyses.

As I recount this painful chapter in history, you will mentally analyze how each side adhered to military principles such as objective, offense, mass, maneuver, simplicity, security, surprise, economy of force, and unity of command.

While the complete study follows a detailed chronology of events based on records from both sides, initial analyses for students are based on a series of essays I’ve written that address various aspects of the conflict. These include the diplomatic prelude, the collapse of deterrence due to perceptions of British defense policy after World War II, initial recognition of the issue, both sides’ initial planning, and the Davidoff incident.

Understanding the Problem

If successive Argentine governments ever considered using military force as a supplement to or substitute for diplomatic efforts to reclaim sovereignty over the Falklands, these actions were discouraged by the perception of British military capabilities and their willingness to use those capabilities to defend their interests. At no time before the deployment of Argentine forces to Port Stanley on April 2, 1982, did the Junta believe the British would respond with military force. Nor did Argentine military leaders at any point before or during the conflict believe that Argentina could prevail in a military confrontation with Great Britain. These two beliefs shaped Argentina’s political and military decision-making process before and during the conflict.

The conflict was the result of Argentina’s longstanding determination to regain sovereignty over the Falklands and Britain’s ongoing commitment to the self-determination of the islanders. For many years, this balance was maintained due to a confluence of personalities and political attitudes on both sides, the Falkland Islands Company’s influence over policy decisions in London, and shifting perceptions of British military power and national interest. These factors set the stage for the decisions that ultimately led to war.

Additionally, Britain’s Conservative Party, facing internal labor unrest and weakened by public discontent, was under pressure. The British Navy’s fear of losing its significance added to this complex decision-making environment. About one thousand lives were lost in the conflict, nearly one for every two island residents. Thirty combat and support ships were sunk or damaged, and 138 aircraft were destroyed or captured. Britain successfully defended the islanders’ "interests," while Argentina’s efforts to regain sovereignty failed. In the aftermath, the British Navy regained prestige in the eyes of political leaders, and Argentina transitioned to civilian governance.

Most writings on Falklands sovereignty devote hundreds of pages to the 150-year diplomatic struggle. Argentines place great emphasis on each step of this process and hold a firm belief in diplomacy, though they recognize the importance of military capabilities as a complement to diplomacy. They see military strength as potentially giving diplomacy a "slight elbow nudge" within certain limits and without crossing the threshold of war. The British, on the other hand, are masters of diplomacy and the use of military force in the classic Clausewitzian sense—as an extension of the political process, regardless of whether or not the threshold of war is crossed.

Argentina’s leadership during the conflict reflected a viewpoint of having “too much history not to act.” In the U.S. and Great Britain, we say that one begins their history with each war, making accounting and decision-making simpler. Whether or not these Argentine viewpoints are historically accurate is irrelevant; what matters is that these criteria had a profound impact on Argentine decisions in the prelude to the conflict.

Of particular interest to military professionals is the gap between the assumptions underpinning British and Argentine decision-making. Between the occupation of the islands on April 2 and the sinking of the Belgrano on May 2, Argentine authorities operated under the belief that they were managing a diplomatic crisis, while the British acted on the conviction that they were at war.

Argentina’s political objective was "a diplomatic solution to regain sovereignty over the islands." Britain’s objectives were "defend the interests of the islanders and punish aggression."

One could argue that Argentina lost the war between April 2 and April 12 by failing to use cargo ships to transport heavy artillery and helicopters for their occupation forces, as well as heavy equipment needed to extend the Port Stanley runway, which would have allowed A-4s and Mirages to operate. The indecision, rooted in Argentina’s preconceived notion that defeating the British militarily was impossible, was a dominant factor in the final outcome.

The Davidoff incident

The Davidoff incident is crucial for understanding the Falklands conflict; it served as the "spark" or, as Admiral Anaya put it, the "trigger." Post-war perceptions of the Davidoff incident in Britain and Argentina differ significantly. Here’s what I believe happened:

In September 1979, Constantino Sergio Davidoff signed a contract with a Scottish company, transferring the equipment and installations of four whaling stations in Leith on South Georgia Island to him. This contract gave him the right to remove scrap metal from the island until March 1983. The Falklands authorities were informed of this contract in August 1980.

The 1971 Communications Agreement allowed travel between the Falklands and Argentina with only a white card. However, in response to UN Resolution 1514, the British registered South Georgia as a separate colony from the Falklands, governed directly from Britain, though administered by the Falklands government for convenience. Argentina rejected this colonial status claim, arguing that South Georgia, like the Falklands, had always belonged to Argentina and therefore could not be anyone's colony.

The problem arose when Davidoff visited Leith for the first time to inspect the installations he had acquired and intended to remove due to their scrap value. British authorities in Port Stanley maintained that no one could disembark in South Georgia without first obtaining permission at the British Antarctic Survey base in Grytviken, also on South Georgia, where passports would be stamped. Argentina, however, argued that the white card sufficed for entry and exit, per the 1971 Agreement.

There remain many unanswered questions regarding the timing, authenticity, and notification to Argentina of Britain’s claim to South Georgia as a separate colony. It is worth noting that both countries interpreted the situation differently. Curiously, Britain chose to enforce rigorous procedures regarding visits to South Georgia just as it was benefiting financially from unrestricted travel enabled by the white card.

The incident formally began when Davidoff left Buenos Aires on the icebreaker Almirante Irizar, which he had chartered, and arrived in Leith on December 20, 1981. Having informed the British Embassy in Buenos Aires of his plans, he traveled directly to Leith without stopping in Grytviken for permission—likely unaware of this requirement—and then returned to Argentina.

Governor Hunt of the Falklands apparently learned of the visit through reports that the Almirante Irizar was in Stromness Bay and from people in Grytviken who reported someone had been in Leith. It seems probable that the British Embassy in Buenos Aires did not inform Hunt. Hunt urged action against Davidoff for bypassing the regulations, but London instructed him not to create issues.

The British ambassador protested to the Argentine government over the incident on February 3, warning that it should not happen again. This protest was dismissed on February 18.

Davidoff apologized at the British Embassy for any inconvenience caused and requested detailed guidelines on how to return to South Georgia to dismantle the installations properly. The embassy consulted Governor Hunt, who did not respond until after Davidoff's departure on March 11. On that day, Davidoff formally notified the British Embassy that 41 people were onboard the Bahía Buen Suceso, an Argentine Antarctic supply vessel. Information about their arrival should have been provided before their landing in Leith on March 19, bypassing Grytviken once more. The workers raised the Argentine flag.

War Triggers- The Argentine Viewpoint

Argentine authorities describe the events of March 19, 1982, as "the trigger." Although these events in South Georgia were far from forcing the key military episode beyond which there was no way out but war—and therefore do not fall into the category of a war starter—March 19 was certainly the spark for a cascade of confrontations and political-military decisions that set the stage for war to begin.

The British reaction to the Davidoff incident led Argentina to adjust its planning. The British Antarctic Survey's message from South Georgia reporting that "the Argentines have landed" polarized British reaction in London. In Buenos Aires, the Junta began considering the possibility of occupying the Falkland Islands and South Georgia before the British could reinforce them. Vice Admiral Lombardo was ordered to urgently prepare Operation Malvinas. Orders and counter-orders ensued.

The British government deployed HMS Endurance to South Georgia to remove the Argentine workers. The British were unaware that Argentina had canceled its initial plan to include military personnel in Davidoff’s legitimate project, but they did know of the Argentine Naval Operations Commander’s directive for two frigates to intercept HMS Endurance if it evacuated Argentine civilians. However, they were unaware that this order was later rescinded by Argentine political authorities, who feared a military confrontation.

Argentine personnel from the Alpha Group, initially intended to participate in Davidoff’s operation, were now redeployed to South Georgia as events unfolded and landed there on the 24th from the ARA Bahía Paraíso. A brief de-escalation occurred on March 25 when Britain learned of ARA Bahía Paraíso’s presence and authorized it to stay until March 28. During this time, Davidoff presented an explanation of his operation to the British Embassy.

The trigger was a (later proven false) report on British television that two nuclear submarines had departed Gibraltar for the South Atlantic. Argentine authorities took this information as accurate. Not wanting to risk a landing operation in the face of a British nuclear submarine threat, they calculated the earliest possible arrival date for the submarines. They were convinced that, from that point on, these submarines would remain stationed there for several years. Argentine authorities likely did not even know the exact time of the submarines' departure.

The Argentine public's support for what was seen as a valid commercial operation under the 1971 Communications Agreement framed a narrative of strong national interest against what was perceived as waning British interest. In an "now-or-never" mindset, the Junta ordered the execution of Operation Malvinas, setting April 2, 1982, as D-Day.

Operation Rosario

The occupation of Port Stanley on April 2, without any British bloodshed, was a model operation—well-planned and flawlessly executed. The 700 Marines and 100 Special Forces members landed, achieved their objectives, and re-embarked as they were replaced by Army occupation forces. The Naval Task Force provided both amphibious transport and naval support.

I do not cover Operation Rosario in detail in this study because it was impeccable. What follows, and the absence of a conceptual military plan for subsequent operations, are of greater interest to my students. Here are two notable incidents:

On the afternoon of April 2, the Argentine Air Force in the Falklands initially denied landing authorization to an F28 carrying the naval aviation commander. The aircraft was eventually allowed to land after a 45-minute delay.

On April 2, the Argentine Air Force requested that the Joint Chiefs transport aluminum sheets to the islands by sea to extend the runway and expand the aircraft parking area for operational planes.

The ARA Cabo San Antonio transported LVTs and members of the 2nd Marine Infantry Battalion to the islands.

Performance of Argentine Transport Authorities

This marked the beginning of Argentina’s struggle to establish effective cooperation among its armed forces. The incident involving landing authorization for the naval aviation commander at Port Stanley symbolized what would soon become a significant coordination issue. The naval transport of runway materials highlighted an inability to set proper logistical priorities for the islands' support.

At that point, the Military Junta was increasingly concerned that resupplying the Falklands would pose a serious risk, as they hoped for a diplomatic solution. With British submarines expected to arrive in the area, any merchant vessel en route to the islands could become a target, risking an escalation they wished to avoid. Thus, resupply had to be limited to what few ships Argentina could load and dispatch before the submarines' estimated arrival.

Giving high priority to artillery and mobility support for the islands—particularly aluminum planks to extend the runway and heavy equipment to facilitate their installation—was crucial. The planks alone were useless without the necessary machinery. Failing to prioritize cargo and maximize the limited transport capacity proved a critical flaw, severely impacting both the naval and land campaigns. It’s worth noting that active U.S. involvement in the conflict became inevitable once extending the Port Stanley runway was no longer feasible.

Triggers of War - The British Perspective

When the South Georgia incident occurred, British Defense Secretary John Nott, Chief of the Defense Staff Admiral Sir Terence Lewin, and Fleet Commander Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse were attending the NATO Nuclear Planning Group meeting in Colorado Springs, where I was also present. As the crisis intensified, these key figures were dispersed: Admiral Lewin traveled to New Zealand, Admiral Fieldhouse to the Mediterranean, and Nott to Europe. During their ten-day absence, the UK observed Argentina escalating its claims.

Demonstrations had erupted in Argentina, and the country’s presence in Thule and South Sandwich was public knowledge in London. The Argentine occupation took place on a Friday, and with key members absent, the British War Cabinet set their objective: "Secure the withdrawal of Argentine forces and restore British administration in the islands."

Recognizing political, economic, and military constraints within Britain, the War Cabinet ordered the British Task Force to set sail on Monday. The fleet embarked, and commercial ships were requisitioned, despite uncertainty about the extent of the effort required. The government’s guiding concept for the operation became "deter and repel," forming the foundation of their initial response.

Argentine Naval Strategy

In Buenos Aires, naval authorities established their strategy:

- Carrier-based interdiction of maritime communication lines was considered and discarded.

- The use of docked vessels in the Falklands as mobile batteries was also considered and dismissed.

- Ultimately, Argentina adopted a “fleet in being” strategy, keeping a reserve fleet for potential postwar Chilean aggression. Avoiding direct naval battles, Argentina opted for a war of attrition—a prudent decision in hindsight.

- The Argentine Navy’s main objective was to inflict damage on the British Landing Force during disembarkation, when British forces would have limited freedom of maneuver.

- Additionally, Argentine concerns about fleet survival were heightened by U.S. Admiral Hayward’s assertion that satellites could track the Argentine fleet’s location at all times.

British Naval Strategy

British naval authorities developed a four-phase strategy to ensure an appropriate force structure:

- Phase One began on April 12, with nuclear attack submarines patrolling west of the islands to enforce the Exclusion Zone.

- Phase Two started on April 22 with the arrival of surface units and lasted until the landing at San Carlos on May 21. The mission was to establish air and maritime superiority in preparation for the landing, marked by a “war at sea” period. During this phase, South Georgia was recaptured, and the ARA Belgrano, HMS Sheffield, and Isla de los Estados were sunk.

- Phase Three began with the May 21 landing, lasting until May 30, focusing on establishing a beachhead, supporting ground troops, and providing air defense. HMS Ardent, Antelope, Coventry, and Atlantic Conveyor, as well as the Argentine vessel Río Carcarañá, were sunk during this phase.

- The Final Phase started on May 30, lasting until the ceasefire, with the mission of supporting ground operations and protecting maritime communication lines. During this period, the British landing ship HMS Galahad was sunk.

Sinking of the ARA Belgrano

On May 1, Vice Admiral Lombardo planned an operation to distract the British Task Force, which, according to Argentine intelligence, was preparing a landing on the Falklands that day. Lombardo’s idea was to form a pincer movement with Task Force ARA 25 de Mayo approaching the Exclusion Zone from the north and Task Force ARA Belgrano from the south, both outside the zone, forcing the British Task Force to abandon its support for the landing.

As ARA 25 de Mayo prepared to engage, the winds calmed, and technical issues limited the ship’s speed to 15 knots. Forecasts indicated continued calm for the next 24 hours, forcing Argentine A-4s to reduce their bomb load from four to one per aircraft. Doubts about the effectiveness of an attack with such a limited payload and reports that the British had not landed as expected led to the order for both task forces to retreat westward.

The ARA Belgrano had maneuvered around the exclusion zone, heading east and then north between the Falklands and South Georgia, to divert British attention from the impending landing and the presence of the 25 de Mayo. Sensing a real threat to his forces, Admiral Woodward requested and received authorization from London to attack the ARA Belgrano outside the exclusion zone to neutralize the risk.

When HMS Conqueror attacked and sank the ARA Belgrano, the Argentine cruiser had been heading westward for fourteen hours. With the sinking of the ARA Belgrano, all hopes for a diplomatic solution faded, marking the start of the naval war.

Maritime Exclusion Zones and Other Navigation Restrictions

The concept of a Maritime Exclusion Zone, as imposed by the British during the conflict, is neither new nor fully understood by all military and political leaders. The pros and cons of a “sanitary cordon” have been debated within NATO for years. Similar terms, such as “Maritime Defense Zone,” have been examined legally and analyzed militarily, with significant disagreements among lawyers regarding its legality under international law, as well as its tactical and strategic value.

Declaratory in nature, like its distant relatives the Blockade and Quarantine, a zone must be announced with clear geographic limits, effective dates, and the types and nationalities of ships and aircraft it applies to.

The blockade, a more traditional military term with a solid basis in international law, is typically defined as a wartime action aimed at preventing ships of all nations from entering or leaving specific areas controlled by an enemy.

The terms pacific blockade and quarantine evolved from blockade laws, with the key distinction being that they are not intended as acts of war. Instead, military action is only anticipated if the targeted state resists. The term quarantine gained prominence in October 1962, when the U.S. president proclaimed a strict quarantine of all offensive military equipment bound for Cuba.

Tuesday, November 12, 2024

Goose Green Next to Waterloo: The 20 Greatest Battles in British History

The 20 greatest battles in British history

The Telegraph reports that the British National Army Museum has published its shortlist of the greatest battles in British history. The public will vote, either online or at the museum, on which one is the greatest.

The battles, in chronological order:

Battle of Blenheim, August 13, 1704, at Blenheim, Bavaria (War of the Spanish Succession)

Battle of Culloden, April 16, 1746, at Drumossie Moor in Scotland (Jacobite Rebellion)

Battle of Plassey, June 23, 1757, at Plassey in West Bengal, India (Seven Years War

Battle of Quebec, June 13, 1759, outside of Quebec City in Canada (Seven Years War)

Battle of Lexington, April 19, 1775, at Lexington, Massachusetts (American Revolution)

Battle of Salamanca, July 22, 1812, at Salamanca, Spain (Peninsular War/Napoleonic Wars)

Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815, at Waterloo, Belgium (Napoleonic Wars)

Battle of Aliwal, January 28, 1846, at Aliwai in Punjab, India (First Sikh War)

Battle of Balaklava, October 25, 1854, at Balaklava, Ukraine (Crimean War)

Battle of Rorke's Drift, January 22-23, at Rorke's Drift, South Africa (Zulu War)

Gallipoli Campaign, April 25, 1915 to January 9, 1916, on the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey (World War I)

Battle of the Somme, July 1 to November 18, 1916, on the Somme River in France (World War I)

Battle of Megiddo, September 19 to October 31, 1918, in Israel/Palestine, Jordan, and Syria (World War I)

Battle of El Alamein, October 23 to November 4, 1942, near El Alamein, Egypt (World War II)

Normandy Campaign, June 6 to August 25, 1944, in Normandy, France (World War II)

Imphal/Kohima Campaign, March 8 to July 3, 1944, around Manipur and Nagaland, India (World War II)

Battle of the Imjin River, April 22-25, 1951, on the Imjin River in Korea (Korean War)

Battle of Goose Green, May 28-29, 1982, on East Falkland (Falklands War)

Battle of Musa Qala, July 17 to September 12, 2006, Helmand Province, Afghanistan (War in Afghanistan)

History News Network

Saturday, November 9, 2024

Malvinas: "The Dirty 12" of Argentine POWs

The Dirty 12 in Malvinas

𝗧𝗵𝗲𝘆 𝘄𝗲𝗿𝗲 𝗽𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗼𝗻𝗲𝗿𝘀 𝗶𝗻 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝗠𝗮𝗹𝘃𝗶𝗻𝗮𝘀 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗮 𝗺𝗼𝗻𝘁𝗵: 𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝘀𝘁𝗼𝗿𝘆 𝗼𝗳 “𝘁𝗵𝗲 Dirty 𝟭𝟮.”

They went down in history as a group of Argentine officers and non-commissioned officers who were held as prisoners by the British for up to a month after the war ended. They became known as “The 12 on the Gallows.” These were officers and non-commissioned officers from the three armed forces who had fought in the Malvinas and remained prisoners of the British on the islands until July 14, 1982 – one month after the surrender.

From the Army: Lieutenant Carlos Chanampa, Sub-Lieutenants José Eduardo Navarro and Jorge Zanela, First Sergeants Guillermo Potocsnyak, Vicente Alfredo Flores, and José Basilio Rivas, and Sergeant Miguel Moreno.

From the Air Force: Major Carlos Antonio Tomba, Lieutenant Hernán Calderón, and Ensign Gustavo Enrique Lema.

From the Navy: Corvette Captain Dante Juan Manuel Camiletti and Marine Command Principal Corporal Juan Tomás Carrasco. Ten of them were captured after the battle of Goose Green – between May 27 and May 29. The other two, Camiletti and Carrasco, were captured days later after they infiltrated enemy lines with an amphibious command patrol.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗼𝗹𝗱 𝗿𝗲𝗳𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗲𝗿𝗮𝘁𝗼𝗿

“I remember the day of the surrender. It was out in the open. The saddest moment of my life,” recalled José Navarro, who was a 21-year-old sub-lieutenant from Corrientes at the time, now a general, who had gone to war with the 4th Airborne Artillery Group. “I remember the incredible silence of 600 men standing in formation in a kind of square.” Those first bitter hours were even harder when, while housed in a sheep-shearing shed, they heard an explosion. They saw a British soldier who, “for humanitarian reasons,” as he excused himself, finished off a wounded Argentine soldier after a munition he was forced to carry detonated. “It was at that moment we said we wouldn’t work anymore. I think we were the ones who started pickets in the country.” The war was over, but in some way, it continued. In San Carlos, they were locked up in a three-by-two-meter room in the old refrigerator, which had an unexploded 250-kilo Argentine bomb embedded in one of its walls. It still had its parachute. In the mornings, they lined up to receive a thermos with tea and biscuits. Since they had no mugs, they had to go to a nearby dump to find cans, which they washed with seawater. They slept on the floor, dressed, curled up, wearing their berets. The bathroom situation was even worse. In one corner of that small space, there was a 200-liter can cut in half. When someone used it, the others had to turn around until they managed to get a blanket to improvise a screen. Every so often, they had to take the can to empty it by the sea. During the time they were held, they were moved from one place to another. One day, they were boarded onto the Sir Edmund. “You’re returning to Argentina,” they were told. But it wasn’t true. Like in the movies, Navarro was interrogated in a cabin, blinded by a powerful light. An English interrogator, who spoke very formal Spanish, bombarded him with questions: How had he arrived on the islands? Where had the artillery in Darwin come from? And the question that obsessed the British: “Did you know there were war crimes in San Carlos?” The British were looking for Lieutenant Carlos Daniel Esteban, who was suspected of having shot down a helicopter they claimed was carrying wounded. They never realized that Esteban was housed on the same ship. They never found him. Navarro was taken back to the refrigerator and locked in a six-by-five-meter refrigeration chamber with cork walls. It had only one door, with a broken window to let in air. A light bulb hanging from the ceiling was the only source of illumination.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗯𝗶𝗿𝘁𝗵 𝗼𝗳 “𝘁𝗵𝗲 Dirty 𝟭𝟮.”

They were left alone for days, with no questioning, which caused them to lose track of day and night. Due to the heat, they stayed in their underwear and once again had to use the filthy 200-liter can. After a day and a half without food, they were finally given something to eat, though they never knew if it was stew or chicken soup. They were hungry but had no utensils. Major Carlos Tomba was the first to act, saying, “I’m eating with my hand,” and the others followed suit. On another trip to the dump, they scavenged spoons and cans. Later, they were taken aboard a ship. When they heard the English national anthem playing over the loudspeakers, mingling with cheers of joy, they realized everything was over. It was June 14. The English captain confirmed it when he approached them to offer some words of encouragement.

𝗧𝗵𝗲 𝗳𝗹𝗮𝗴, 𝗮 𝘁𝗿𝗼𝗽𝗵𝘆 𝗼𝗳 𝘄𝗮𝗿.

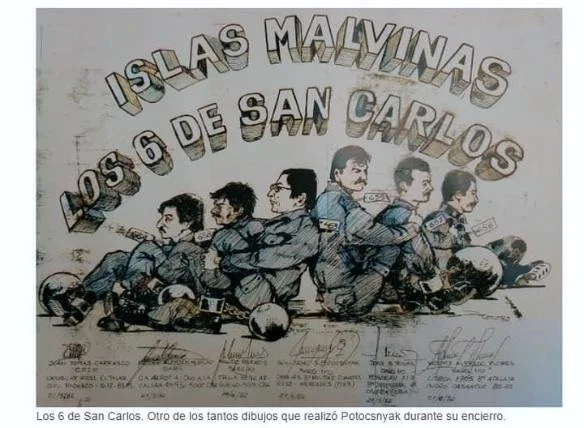

Navarro recalled that at that point, security relaxed so much that Corvette Captain Dante Camiletti came up with the wild idea of taking over the ship. However, while the English showed little concern for their prisoners, they were visibly wary of Argentine aviation, especially the Exocet missiles. On the Sir Edmund, they were on their way back to the mainland when Navarro entered a random cabin and took an English flag. “You idiot!” his companions scolded him. They managed to hide the flag inside a panel in the cabin ceiling before the English, frantically searching every corner of the ship, discovered it. When Navarro stepped onto the dock in Puerto Madryn, he showed the English the flag, which he still has framed along with copies of the famous drawings made by Potocsnyak, one of his fellow prisoners. “Do you know what it means to surrender on Army Day?” asked the Santa Fe-born Guillermo Potocsnyak, known as “Poto” or “Coco” for his hard-to-pronounce Croatian surname. A stout senior sergeant who had gone to the islands as a first sergeant with the 12th Infantry Regiment, he later became a local hero.

𝗔𝗻 𝗮𝗿𝘁𝗶𝘀𝘁 𝗮𝗺𝗼𝗻𝗴 𝘁𝗵𝗲 𝘁𝘄𝗲𝗹𝘃𝗲

After fighting at Goose Green and San Carlos Bay, Potocsnyak was captured. While helping collect bodies of fallen Argentines, he stumbled upon a frozen body that suddenly blinked. He placed the soldier on the hood of a carrier, and although the soldier lost a leg, Potocsnyak saved his life. A popular figure among his peers and even his captors, Potocsnyak had a knack for drawing. He traded chocolates and cigarettes for paper, pencils, and pens, and his drawings began circulating, crossing all boundaries. Many of them, he says, are likely in the United Kingdom today. He’s the author of the famous sketch of the 12 officers who were held until July 14. In the foreground is Tomba, clearly wearing a fanny pack that they all wore as life vests. Even after June 14, the British hadn’t ruled out Argentine air attacks. On seeing the drawing, someone—he couldn’t remember who—suggested, “Call it ‘The 12 on the Gallows.’” It references the title of a 1967 war movie where a dozen dangerous prisoners were assigned a risky mission in German territory during World War II. Potocsnyak remembers that from time to time, the English would subject them to searches with batons while they had to stand facing the wall. When he told an Englishman, “Shove that baton up your…,” the Brit responded, “Don’t play smart; I speak Spanish better than you.” In the postwar period, Potocsnyak lost his wife, but years later, while studying Croatian—he has dual nationality—he met his second wife. “Family was my first support,” he admitted. He has two children and four grandchildren. He studied to become a history teacher, not to teach but “to understand what we went through there, and also as a way to feel useful.” His life as a veteran wasn’t easy. He had to leave Córdoba, where he lived, because people always asked him about the war, and he felt he couldn’t turn the page. Time eventually helped him move on. Of that famous group of 12, he highlights that “Major Tomba is a true gentleman, an extraordinary person.” After Corvette Captain Dante Camiletti, Major Carlos Tomba—the highest-ranking officer and a 36-year-old from Mendoza who had fought as a Pucará pilot—assumed leadership of this diverse group. Now a retired brigadier, Tomba lives in Mendoza, where his last name holds historical significance in the province. His first clash with his captors came over defending his belongings—his helmet and leg straps from his ejection seat. He managed to keep them, along with pajamas given to him by his wife. The helmet and leg straps are now on display at the Air Force Museum in Córdoba. He recalls that the early days were the hardest: 48 hours without water, followed by a can of pâté. Unsure of what the next day would bring, they only ate half of the can’s contents each time. As the group’s English speaker, he acted as their spokesperson and interpreter with the British doctor who treated the wounded Argentines. He also negotiated to remove the 200-liter can from their tiny room and managed to have their meals served according to the local time, not British time. Tomba saw boxes of missiles labeled “USAF” from the U.S. Army. He focused on keeping his mind active; they had no idea what was happening on the islands and didn’t want to waste energy, as they often felt faint from the lack of food. He even devised an escape plan, thinking he’d found a weak point in the guards’ security. One night, he climbed a wall intending to slip away in the dark, but a blow to the mouth brought him back to reality. He recalls some laughable situations, like the day 40 of captivity. They were in San Carlos, and for the first time, they were allowed to bathe. They were made to strip, each given a towel, and ordered to run 200 meters to a shack, where an Englishman on the roof poured hot water on them.

“𝗗𝗼 𝘄𝗵𝗮𝘁 𝘆𝗼𝘂 𝗰𝗮𝗻.”

In 1982, Chanampa was a 27-year-old lieutenant. From Villa Dolores, where he now lives, he recalled that when they surrendered, they were exhausted and conveyed this to the English, who then made them dig latrine pits and collect munitions. He is critical of the war’s leadership. He couldn’t believe what he was told when he asked for vehicles to move artillery pieces to hinder the British advance: “I have nothing to tow the cannons with.” The reply was, “I don’t know, get horses, do what you can.” They received orders that were impossible to carry out. In the early days as a prisoner, he slept alongside other Argentines on makeshift cots made from ammunition boxes. He was interrogated twice, once at the refrigerator in San Carlos and a second time in a sheep pen separated by a stream, where they were taken on a gloomy morning in a rubber boat. They were made to undress in the open air, interrogated, dressed again, and returned. However, Chanampa noted that the English knew every detail of the Argentine positions and their real capabilities. He was also struck by the youth of many British soldiers and that some officers he spoke with showed little interest in the war. He said that when morale was low among the group, they would read aloud letters some comrades had saved from family members. Chanampa was one of the many who had to start from scratch multiple times. He worked in commerce, became a textile company manager, and later a director in an insurance company. In Villa Allende, he seems to have found his place in the world.

𝗣𝗿𝗶𝘀𝗼𝗻𝗲𝗿𝘀 𝗼𝗻 𝗔𝘀𝗰𝗲𝗻𝘀𝗶𝗼𝗻 𝗜𝘀𝗹𝗮𝗻𝗱?

Five hundred kilometers from Villa Allende lies the town of O’Brien, named after an Irishman who risked his life for Argentina in the independence wars. There was born Jorge Gustavo Zanela, who, at 23 and with the rank of sub-lieutenant, went to war with the 4th Artillery Group as part of Task Force Mercedes. When he was captured, like many others, he was taken in a Chinook helicopter to San Carlos. While in the refrigerator, he grew hopeful when they told him they were taking him to Uruguay, but at the last moment, he was taken off the ship along with other officers, selected based on seniority and specialty. Zanela still keeps under the glass of his desk a Red Cross certificate for his transfer to Ascension Island, a transfer that never happened. He was interrogated by an Englishman with a military interpreter from Gibraltar who insisted on knowing about Argentine positions and obtaining maps.

𝗘𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 𝗽𝗼𝘂𝗻𝗱𝘀 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗲𝘅𝗽𝗲𝗻𝘀𝗲𝘀

Zanela has vivid memories of the wounded English soldiers affected by the Argentine air attack on Fitzroy Bay, many of whom suffered severe burns. June 8, considered the blackest day for the British fleet, saw Argentine planes sink three ships, damage a frigate, and leave 56 British soldiers dead and 200 injured. He remembers that “the 12 on the gallows” were on a ship crossing the English Channel. Representatives from the Red Cross, mostly Uruguayans and Spaniards, would occasionally visit them. They would even argue with the English, taking down their information as prisoners of war and carrying letters for their families, which were sent through Switzerland. Like other prisoners, they were given eight pounds for expenses, though they spent only a small amount, saving the rest as a memento of the war. Toward the end, they managed to get a radio and learned about Pope John Paul II’s visit. The English themselves informed them of Argentina’s elimination from the World Cup, celebrating loudly when Argentina surrendered.

Zanela did not join the main group of prisoners taken to Puerto Madryn. Instead, he remained in San Carlos with other officers as the Argentine Air Force continued to pose a threat, initially refusing to observe the ceasefire. Finally, on July 14, they were moved to Puerto Argentino and boarded the Norland. Once back on the continent, they were forbidden from speaking. In Trelew, they received clean clothes, and after several layovers, an Army plane brought them to their unit in Córdoba.

Now Colonel Jorge Zanela heads the Office of Veterans Affairs for the Malvinas War. His office in Palermo resembles a small museum dedicated to his time in the South Atlantic conflict. On one wall, there’s a yellowed copy of the sketch of “the 12 on the gallows.” In 2015, he returned to the islands and visited the refrigerator, now abandoned and in ruins, where the hole left by the undetonated Argentine bomb remains. He wasn’t allowed to enter due to the danger of collapse. Over the years, the group has never reunited. Lieutenant Hernán Calderón passed away on March 24, 1983, in a training flight accident, and First Sergeant José Basilio Rivas died in a car accident on December 22, 2001. Some of the twelve retired shortly after, while others continued their military careers. But they never stopped being part of “the Dirty 12.”

Wednesday, November 6, 2024

Biography: Lieutenant Colonel Cruz Cañete (1815-1868)

Lieutenant Colonel Cruz Cañete (1815-1868)

Lieutenant Colonel Cruz Cañete (1815-1868)

He was born in Buenos Aires in 1815, the son of Mariano Cañete and Leonor Peñalva, both from Buenos Aires. He entered military service in June 1835 as a soldier in the 4th Campaign Regiment’s Line Squadron.

In 1837, as a standard-bearer (a rank he achieved in 1836), he participated in a battle against Chilean Indigenous groups who had attacked friendly chiefs Llanqueleu and Francisco. That same year, he fought against the same forces under Lieutenant Colonel Quesada, and later in the Battle of Loreto on December 22, 1838, against a large contingent of Chilean and Ranquel Indigenous fighters, directly under Colonel Hilario Lagos as a cavalry lieutenant. In 1842, he was severely wounded in another action against Indigenous groups, under Captain Seguí’s command.

He continued his service at Fort Junín until 1844 as a lieutenant, then transferred to San Nicolás under Colonel Juan José Obligado’s command, where he remained until June 12, 1845. He subsequently served under General Lucio Norberto Mansilla and participated in the Battles of Vuelta de Obligado (November 20, 1845) and Quebracho (June 4, 1846) against Anglo-French naval forces, commanding a squadron he had personally trained. Mansilla, in a report dated November 15, 1860, described Cañete as “a disciplined, exemplary officer, devoted to his duties.”

He was promoted to captain in 1848 and major in November 1851. That same year, with his squadron, he joined a division that General Mansilla assigned to Colonel Julián Sosa, under whom Cañete fought in the Battle of Caseros. Mansilla had assigned command due to an illness requiring his return to Buenos Aires.

When Colonel Hilario Lagos rebelled against the Buenos Aires government on December 1, 1852, Major Cañete was stationed in San Nicolás, where Colonel José María Cortina, acting under Lagos’s command, enlisted him to help disarm groups moving towards San Nicolás after the disbandment of the Buenos Aires besieging army on July 13, 1853, maintaining order “with honor, activity, and patriotism” (Cortina’s report, November 20, 1860).

In November 1854, during the Buenos Aires invasion led by enemies from the province of Santa Fe and commanded by General Jerónimo Costa, Cañete, then a retired major, offered his services to Lieutenant Colonel Mariano Artayeta, the local military commander. Artayeta accepted, tasking him with organizing local cavalry forces, which he did successfully, leading 50 cavalrymen in capturing the defeated forces from El Tala and performing other missions, gaining the Superior Government’s recognition.

In January 1856, he accompanied Colonel Esteban García, commanding the first skirmishes against the invading forces of Generals Flores and Costa at Ensenada and Villamayor, where Costa was defeated and executed. As part of the Extramuros Regiment under Colonel García, he fought in the Battle of Cepeda, leading a squadron. After the dispersion of Buenos Aires cavalry, Cañete reached Morón, then returned to the capital and participated in the brief siege until the treaty of November 11. In a report dated December 17, 1860, Colonel García praised Cañete’s conduct: “I have nothing but respect for his morality, skill, and dedication to service.”

He participated in the Battle of Pavón and joined the "General San Martín" Regiment under Colonel García when the Paraguayan War began, taking part in the battles of Yatay, Uruguayana, Paso de la Patria, Itapirú, Estero Bellaco del Sud, Tuyutí, Yataytí-Corá, Boquerón, Sauce, and the cavalry demonstration at San Solano on September 22, 1866.

Promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel, he received full rank on May 8, 1868. However, he was forced to return to Buenos Aires due to severe dysentery. Complications from “malaria” led to Lieutenant Colonel Cruz Cañete’s death in the capital on July 28, 1868, at 53.

On January 18, 1858, he married Rosario Rodríguez, a widow from Buenos Aires, daughter of Colonel Ramón Rodríguez and Concepción Lahite. She passed away in 1894.

Sources

Efemérides – Patricios de Vuelta de Obligado.

www.revisionistas.com.ar

Yaben, Jacinto R. – Biografías argentinas y sudamericanas – Buenos Aires (1938).